Giving Up on Great Plans? Transforming Representations of Space in City Plans in Russia and Sweden

Lisa Kings is a researcher at the Institute for Research on Migration, Ethnicity, and Society (REMESO) at Linköping University and a senior lecturer at the School of Social Sciences at Södertörn University. Address for correspondence: School of Social Sciences, Södertörn University, ME241, SE-141 89, Huddinge, Sweden. lisa.kings@sh.se.

Zhanna Kravchenko is a senior lecturer in the Department of Sociology at Uppsala University and a researcher at the School of Social Sciences at Södertörn University. Address for correspondence: Department of Sociology, Uppsala University, Box 256, 751 05, Uppsala, Sweden. zhanna.kravchenko@soc.uu.se.

Research for this article was conducted through support by the Baltic Sea Foundation, Södertörn University, and the Faculty of Social Sciences (School of Social Work) at Lund University. We would like to offer special thanks to three anonymous reviewers and editors of Laboratorium for their insightful and constructive criticism. The authors bear equal responsibility for all flaws that remain and are listed alphabetically.

This article analyzes representations of urban space by exploring city planning during the last half century in Stockholm and Leningrad/Saint Petersburg. City plans that constitute the empirical foundation of the article were enforced during the nodal points—1950s–1960s and early 2000s—of the historical development of both countries and reflect specificities of their ideological and sociopolitical heritage. Our study explores how representations of space—crystallized as ideas about goals and possibilities for spatial planning—have changed over time and how they reflect larger political, economic, and ideological transformations in Sweden and Russia. Two overarching themes are identified in our analysis. First, the ideal of equality, which dominated both the socialist and social democratic ideologies in the 1950s–1960s and provided opportunities for extensive normative control and manipulation of social life by means of a planned physical environment. Second, the ideal of the “European/global” city is distinguished in the early 2000s as a means of promoting economic development by incorporating new actors and shifting the focus to a more market-oriented approach to planning.

Keywords: City Planning; Representations of Space; Stockholm; Saint Petersburg

The way space is organized in society determines the following important aspects of its functioning: location, the use and value of economic resources, density, propinquity and cohesion of the population, the exercise of public and private practices, and manifestations of power and protest. Modern urban life takes place in a planned society; the logic behind any planning is authoritative, constituted through a set of power relations that manifest themselves spatially in both material and immaterial ways (Perry 1995:143). In the theoretical discussions of urban sociologists, city space often appears as a backdrop to social actions and experiences, a location for various economic, social, and political processes (Gans 2002). However, public policymakers who formulate targets and provide instruments for solving social problems in specific urban environments also formulate conceptual definitions of these problems and map their role in urban space. Ideas about the appropriate forms and use of space play a crucial role in the process of public governance. Although attempts to control and plan social life do not always result in the anticipated outcomes, official perceptions of space create specific, normative structures within which social life operates.

This article analyzes urban planning from a sociological perspective by exploring conceptualizations of space. The main focus is on city planning and the trajectory from postwar modernization to neoliberalization in two European cities: Stockholm (Sweden) and Leningrad/Saint Petersburg (Russia). As Molnar (2010) has noted, the planning process is often treated as a passive instrument of politics or capital, while in fact the symbolic aspects of planning carry significant weight, as they provide relevant representations of spaces in addition to economic and political goals and means of spatial development. The sociological perspective employed in this study allows us to examine the unfolding of the ideological principles embedded in main documents for city planning, with the aim of linking commonalities and differences in sociopolitical contexts to their perception of spatial organization.

The research literature examining the shifts in ideological and organizational prerequisites has, in large part, been focused on a limited number of empirical contexts (Brenner 2004; Brenner and Theodore 2002). In line with Marcuse and van Kempen (2000), our point of departure is a comparative approach which takes into account the parallel processes of continuity and change in specific national contexts. With this approach we also aim to challenge the underlying notion (especially evident when comparing the East and the West), where one geographical entity (the East) is seen as being at an earlier stage of development and should, with time, follow its counterpart (the West). Such a view establishes a deterministic relationship between time and space, wherein space becomes subordinated by time and geography is restricted by history. Following Massey, we see the need to address space as the simultaneity of difference that cannot be annihilated by time (2005:90).

Using the general city plans[1] of Leningrad/Saint Petersburg (1966 and 2005) and Stockholm (1952 and 1999), we strive to illuminate how normative perceptions and ideological paradigms are transposed into a spatial dimension and how social and economic goals are translated into questions of space. Saint Petersburg is a city that during its rather short—by European standards—history has acquired both imperial and socialist heritage and has gone through an extremely rapid ideological, organizational, and economic transformation since the abrupt fall of the Soviet Union, most recently reinventing itself as a “world city” (Golubchikov 2004). Stockholm, which can be seen as a physical manifestation of mid-1900s social democratic politics (cf. Hall 1999), has gone through a more timid, but nonetheless significant, form of reconstruction (Hort 2009). Our analysis compares two moments in the history of both countries—the period of 1950s–1960s and the early 2000s—in order to explore how national and global ideological processes are reflected in different localities across time. The selected countries have experienced significant systemic shifts, albeit of a different magnitude, over the last several decades. This provides an opportunity to reveal the nuances of the transformation of planning ideals in countries with differing balance of power relations, political-institutional arrangements, and patterns of socio-spatial inequality.

The article is organized as follows: We first present the theoretical grounds for our analysis by addressing developments in planning and urban theories. Then we discuss the study’s methodological considerations, followed by a presentation of the results. The final section provides an analysis of contemporary transformations with regard to the ideological priorities for urban planning in the selected cases.

Theoretical Perspectives on Urban Planning

As Gans has argued, the processes of spatial planning—“how and why … [planners] affect land users the way they do and on what grounds” (2002:331)—is a topic in contemporary sociology that deserves more attention than it has received. Defined very broadly, social planning as such is a method of governing and control, oriented towards some common good (Herington 1989:1). An understanding of the spatial environment as a collective good that needs to be managed publicly and strategically is part of the definition of urban planning in any modern society.

Over the last sixty years, urban planning theory and practice in the Western world have experienced significant changes: from being seen as an exercise in physical planning and design to being understood as a rational process of decision making (Taylor 1998) and from a government action aimed to correct “market failures” to an attempt at maintaining political and social stability by meeting the interests of various political actors (Klosterman 1985). In contrast with Western economies where planning required theoretical legitimization, in countries with command economies planning was an inherent part of the ideological machine of social and economic regulation, subsequently losing its relevance after 1991 (Golubchikov 2004). This process of paradigm shift in Western planning theory coincided with a similar trend in the development of urban theory. Gottdiener and Feagin (1988) juxtaposed two approaches to conceiving urban space: an urban ecological perspective and a neo-Marxist critical perspective. They suggested that one of the characteristic theoretical points of the former approach was that social development was seen as an equilibrium-seeking process that balanced population, social organization, environment, and available technology, while the latter approach was focused on inequalities and class antagonisms as the primary motors of social development.

Although planning theory rarely incorporates the theoretical concepts of urban theorists, we can conclude that all theoretical perspectives within these two closely related disciplines conceive of public planning as a process of state intervention into the self-regulating functioning of the market. They differ largely in how they justify why it should be employed and what measures it should engage (cf. Fainstein 2000). The very diversity of viewpoints on urban planning’s purpose and mechanism is an indication of the fact that “the order we observe [in the organization of human settlement patterns] is not all-encompassing and rational, but strongly influenced by social values, conflict, and political interpretations of what social and spatial order should actually look like” (Scott 1992:2). The idea that urban planning cannot be seen as a rational problem-solving function of public policy stimulates research on the role of ideology and culture as organizing frameworks for planning. The visions and ideals always inherited in planning discourses and practices can be analyzed via different philosophical and sociological approaches (cf. Gunder 2005; Yiftachel 1998; Young 2008).

One such approach has successfully deployed the conceptual model of Henri Lefebvre (1991), which emphasized the dialectical interactions between the physical environment and social relations. Lefebvre’s spatial triad includes three interacting elements: spatial practices (perceived space), representations of space (conceived space), and spaces of representation (lived space). All three elements have been developed further in both urban and planning theory (e.g., Allen and Pryke 1994; Leary 2009; Zukin 1995), demonstrating their high potential for application in empirical research on a wide variety of issues. For the purposes of this study, we focus specifically on representations of space, which Leary defined as “rational, intellectual conceptions of urban areas for analytical planning and administrative purposes” (2009:196). Drawing on his approach we conceptualize planning as the process of conceiving of space and formulating representations of space by people who in their professional work, as for example city planners and architects, are responsible for the control and regulation of space (cf. Franzén 2004).

As Lefebvre and other neo-Marxists after him asserted, representations of space tend to be regarded as images of social reality. This is a misconception that conceals the normative aspects of these images, making them powerful tools for transforming society and hiding the social relations that facilitate the reproduction of space: “power defines what counts as rationality and knowledge and thereby what counts as reality” (Flyvbjerg 2003:319). Moreover, as Harvey (1985) suggested, planners do not strive to realize some abstract universal understanding of common good; rather, their goals are defined by the need to reproduce social relationships with respect to production, distribution, and consumption. Ideological boundedness is fundamental for spatial planning in any social system. Lefebvre, in his critique of the modern process of production of space, emphasized the fact that there never were “real” differences between capitalist and communist-socialist systems in terms of the goals, instruments, and strategies used for the organization of space (1991:54). Brown (2001) provided an illuminating empirical example of this argument by revealing how town planning and construction in both the US free market and the Soviet planned economy had little regard for the needs of prospective inhabitants, focusing primarily on the need to exploit natural resources and accelerate industrial growth.

The principles of spatial planning and public management are nevertheless related to modes of public governance. The governing tradition defines how different societal actors—including state, market, noncommercial, and nongovernment organizations—obtain, manage, and use various kinds of resources. For instance, the tradition of Soviet planning, with its emphasis on centrally developed plans, involved setting targets for production in all spheres of social life—from movies to heavy industries. In the classical liberal tradition the state issues guidelines to economic actors and relies on the market’s demand-supply mechanisms of regulation in most socioeconomic spheres. Nowadays, there is hardly any country realizing such ideal-typical planning traditions in practice. As Healey and Williams (1993) demonstrated, two common tendencies have emerged in the practice of European planning systems: towards a greater flexibility on one hand and toward a rediscovery of the importance of planning on the other.

The critical urban theory that we attempt to bring into the analysis of planning ideals—representations of space—traditionally focused on critiquing ideas and discourses about capitalism as well as those of capitalism itself. The major concern of urban critical theory is to create an intellectual arena for discussions about democratic, socially just, and sustainable forms of urbanism (Brenner 2009). Therefore the analytical tools created within this approach are not limited to the capitalist social system and are also useful in the analysis of societies that (used to) belong to the realm of “really existing socialism” or of the countries trying to implement a “middle route” between capitalism and socialism (Hall 1999; Hort 1990).

Methodological Considerations for the Analysis of City Plans

The two cities we have selected as case studies have experienced different approaches to planning over the course of their history. Saint Petersburg has evolved from the imperial capital of the Russian Empire to a second-tier yet culturally esteemed Soviet city to a rejuvenated capitalist metropolis. It is one of the few cities that had general (usually twenty-year) development plans throughout its history. The history of city planning in Saint Petersburg/Leningrad includes five general plans: 1935/9, 1948, 1966, 1987, and 2005. This study analyzes the last four decades of the city’s history with two nodal points—the 1960s[2] and the 2000s. In Russia, the general plan is defined as a guiding document for city developers, which outlines trends in the use and management of city space but does not give precise details of these trends. Usually plans will include specifications for prospective transport development, infrastructure (heat, energy, water and gas supply, sanitary services), industrial construction and development, housing construction and development, business construction and development, recreation construction and development, and development of protected areas (parks) and constructions (e.g., UNESCO heritage sites) (Proekt general’nogo plana 1964; Kamenskii and Naumov 1966; Zakon Sankt-Peterburga No. 728-99 2005).

The other case selected for this study is Stockholm, which has a long history of different approaches to urban governance stretching from the time it was a small merchant city during the mid-1200s to becoming the capital of Sweden in the 1600s to a laboratory for social democratic interventions during the 1900s. The history of city planning in Stockholm comprises three general plans: the first dates from 1952 and was applied for development planning until 1991, the second was enacted in 1999, and the most recent was officially accepted in 2012 after a long period of public debate. Since 1987, it has become obligatory in Sweden to develop overarching plans for city development, and they have been renamed “outline plans” (översiktsplaner). All documents are available for open public access. The general/outline plan determines the fundamental physical characteristics of the city space, for instance prescribing where new housing districts (bostadsområden) would appear. It acts as a guiding document with the objective of being flexible. It is valid for a period of five years, after which adjustments can be introduced. The general plan is complemented by binding city plans, which embrace smaller areas and determine more precise targets for city development, such as when and at what cost residential complexes will be built.

The choice of selected plans was made with respect to their comparability in time and their role in specific historical-ideological periods in both contexts. The Stockholm general plan from 1952 illustrates the central aspects of social democratic city planning during the “golden age” of the Swedish welfare state. The 1966 plan of Leningrad demonstrates the ideological highlights of the period of construction of socialism in the Soviet Union. These two plans were then contrasted to two contemporary plans that are most comparable with regard to time and societal processes in both countries—1999 for Stockholm and 2005 for Saint Petersburg. The Stockholm plan is intertwined with an overall restructuring of the Swedish welfare state, which among other things has included a reduction in public spending and introduced collectively financed but privately organized social services of various types (Hort 2009). The Saint Petersburg plan encompasses the long period of post-Soviet capitalist transformation that, like the Swedish case, contests the role of the state in planning social and economic development and broadens the scope of agencies involved in the planning process.

We have limited the empirical basis for this study to four general plans—two from each country—for reasons of methodological consistency. It is undoubtedly a limitation of this study that it does not provide a comprehensive analysis of all the plans existing in both cities and that the selected plans were not developed in exactly the same period. Moreover, the development of general plans in both cities does not directly reflect all historical shifts in planning approaches. Ruoppila (2007) for instance has highlighted fluctuations in the legitimacy and importance of planning as a development strategy in the postsocialist context, indicating that there was a significant shift from centralized and detailed planning during the socialist period to free-market oriented planning practices in the early 1990s to (re)integration and strengthening of spatial regulations into economic and managerial practices in the late 1990s. Nevertheless, the selected city planning materials do provide an opportunity to capture major shifts in representations of space in contemporary ideological and socioeconomic contexts by contrasting them with historical forms of strict vertical planning: social democratic and state socialist city planning.

Since this study is focused on the transformation of ideas about space over time and across national contexts, we use city plans as “books of ideas” and not mere policy documents or drama stories (Mandelbaum 1990). We aim to highlight the central points of each plan and connect them to ideas and conceptions of different ideologies and regimes. More precisely, we examine sections that define goals and targets of the plans, their formulation, degree of precision, and order of appearance, in order to capture the overarching ideology embedded in representations of space. Therefore, details on how the plans were developed, which agencies and actors were involved, and what power relations were constructed are excluded from our analysis. Such an approach is not common among researchers because the process of conceiving of space is never formally separated from the process of institutionalizing and enacting plans. Nonetheless, as Friedmann (2005) asserted, general plans are not meant to serve as “daily blueprints.” Because a large part of planning coordination and urban management occurs spontaneously among various organizations, the content of representations of space contained in plans can be analytically distinguished from the role of agency in the planning process.

Our methodological strategy is based on two steps: first we highlight the specifics of either case and then distinguish convergences and deviations between them. The nature of historical comparative research provides an opportunity to simultaneously reveal common properties despite variation in geographical locations and structures of realization and, at the same time, to recognize formal variation in common phenomena. Selecting Sweden and Russia provides us with a unique opportunity to address the differences in the ways that states have tried to compensate for and/or overcome negative outcomes of market forces (the traditional social democratic and socialist approach respectively). With a comparison over time, these cases also highlight how a more contemporary and globally unified perspective on urban development materializes in contexts with different systemic legacies. All translation from Swedish and Russian are ours unless otherwise stated.

Conceiving of Space: General Goals, Objectives, and Principles

The Swedish social democratic welfare state originated in distrust of the power of the market to serve the public good, and the role of cities and urbanization was a central issue in its creation. In contrast with a socialist ideal of democratization of ownership, the social democratic perception and practice were based on the commodification of space, albeit strictly controlled through centralized planning. In Sweden during the time of the 1952 plan, centralized planning involved shared responsibility between state and local authorities with public funds, cooperative ownership of apartment blocks, and state aid for construction and production (Franzén and Sandstedt 1981). This meant that the planning and development of cities was to a large extent controlled by the state and local authorities, where the involvement of private actors was primarily limited to the production of housing.

During the 1980s, public control of city planning decreased, and the possibilities for private actors to influence the city planning process increased. Internal processes of ideological transformation and external processes of globalization when Sweden entered the European Union in 1995 accompanied this change. Although the current restructuring of the Swedish welfare state in favor of market expansion cannot be compared with the drastic transformation that has occurred in Russia, the new conditions for city planning follow, to some extent, similar patterns.

In the Soviet Union, urbanization was viewed as an integral, essential part of the process of socioeconomic and cultural development. It was seen as a two-stage development: concentration and accumulation of the “achievements of the material and spiritual production” in large cities and then dissemination of these achievements to peripheral towns and rural settlements, giving new impulse for increasing the potential of the centers (Kogan 1982:9). This duality was expected, on the one hand, to stimulate differentiation among different regions, cities, and even city districts and, on the other hand, to gradually eliminate these differences and increase equality among them. This idea of translating progress from the center to the periphery fits very well into the conception of centralized planning as such, defining an archetype of Soviet governance.

By the end of the communist era, many of the problems confronting Soviet planners on the ground were not essentially different from those being faced in the West (French 1995). Among the significant specific challenges that were formulated in academic discussions were the need to develop planning legislation, to reconsider the technocratic approach, and to establish relationships between agents within the public sector and between the public and the private sectors (Golubchikov 2004). The reforms of the 1990s promised a new impulse for urban development as a result of opened opportunities for local self-government and private initiative and new ideological prospects. All these processes were mirrored in the history of the transformation of Leningrad/Saint Petersburg and its central plans.

The following empirical presentation includes a general overview of each plan as well as a description of central themes identified in them, focusing especially on the ideal of equality in the first time period and the ideal of the “European/global city” in the contemporary period. A detailed analysis of these themes is provided in a separate section.

Stockholm (1952)

In Sweden, the relatively late urbanization process conveyed serious challenges for city planning during the 1940s and became an essential part of the ambitious project of the welfare state. The expansion of Stockholm and the renewal and demolition of older settlements were essential to attracting a labor force for an intensified industrialization (Franzén and Sandstedt 1981). The development of the city was dramatic, and the extensive planning was aimed at avoiding mistakes that had occurred in countries where urbanization had started earlier (Generalplan för Stockholm 1952:114). From the 1940s, the character of state interventions changed: sporadic and supporting measures that were gradually introduced during the two preceding decades developed into an overreaching practice of state planning. The Stockholm plan of 1952 can be seen as an illustration of this new practice. It took seven years to complete and contained a total of 500 pages divided into four parts: 1) conditions, 2) norms and principles, 3) the plan, and 4) a timeline for realization. Two issues were central for the formulation of the plan’s main goals: continuous population growth and housing provision.

The plan underlined that further industrialization and economic development required a labor force. Since the location of industries was strongly linked to large urban areas, it was essential to provide the labor force with attractive residential conditions in the city (in terms of standards of living, affordability, and availability for all) and means of transportation (Generalplan för Stockholm 1952:113). Special attention was paid to the “sociopsychological environment,” facilities for personal development, and social adaptation for coming generations of citizens:

The size of the population within the borders of Stockholm city is not a precondition but an effect of planning. The size of the population depends on the standard of how, on one hand, upcoming residential area will be built and, on the other hand, how sanitation of the inner city will be carried out. (Generalplan för Stockholm 1952:28)

In other words, the plan did not project the future population growth but considered it to be in direct proportion to how comfortable the future city environment was to be.

City expansion was realized foremost through the construction of new housing districts on unexploited land on the outskirts of the city. The new ideal for the suburbs was the so-called residential area, planned as a holistic concept with a neighborhood center, public space, green space, and recreational area, in contrast to the old inner city, where the living spaces were often scattered (Generalplan för Stockholm 1952:115–124). These areas were to be organized as functional units, which also included detailed plans for housing complements and collective consumption.

The calculations of provisional norms for construction required formulation of standardized everyday routines:

The youngest and the oldest rarely go further than one block away [from home], and according to research by the Department of Parks and Recreation children in the city center rarely go more than 200–300 meters to play. The married housewife has little opportunity for mobility especially during the period when small children are at home. (Generalplan för Stockholm 1952:124)

A new kind of city was to be erected, where the vibrancy of the metropolitan inner city with access to culture and work would be combined with a peaceful green environment and good conditions for raising a family. An enlarged network of public transport and increased possibilities for private car traffic would connect the city’s different parts and reduce long and time-consuming commutes.

In the section “Norms and Principles” (Chapter 6), where an extensive discussion of the aim and the preconditions of planning are presented, it is made clear that planning cannot be limited to technical and economic efficiency. The physical wellbeing of inhabitants, their personal development, and social adjustment are contrasted with technological and economic development, and all elements must, according to the plan, be joined together in a holistic vision:

The influence of the present on the future will be so much stronger if in our planning we narrowly adapt our solutions to the needs of today or tomorrow. Our vision of the future will therefore always constitute a weighty condition in planning. (Generalplan för Stockholm 1952:46, English in the original[3])

Leningrad (1966)

Our first Soviet/Russian case dates to the mid-1960s, when it became clear that the first post–World War II plan (1948) had outgrown its usefulness, and the Thaw signified a new stage in the city’s development, allowing the formulation of new priorities different from those of the reconstruction period. The new plan provided general guidelines for the city’s 16 districts in the form of five-year plans during the next quarter of the century (Ruble 1990).

The structure of the plan covered six major issues: 1) the size of the population; 2) housing construction; 3) social infrastructure; 4) territorial development; 5) transport, plumbing, and heating installations; and 6) suburban areas. In contrast to Stockholm’s 1952 plan, the plan for Leningrad did not have a separate section outlining guiding norms and principles. As the main architect of the plan would emphasize several years later, there were two primary goals: to limit population growth and to move the city closer to the sea (Kamenskii 1972). Our analysis highlights that these two goals had a common denominator—improving the living and housing standards of the population.

The first goal was common for large metropolitan areas in the Soviet Union (including the capital city of Moscow [see Seniavskii 2003]), frequently motivated by the problem of high population density negatively impacting quality of life. More importantly, it was dictated by poor housing conditions and the fact that housing construction was financed on a residual basis, leaving the government unable to meet the demand for adequate housing. In contrast to the Stockholm plan’s focus on expanding the labor force, decreasing the density of population was so important that the drafters of the Leningrad plan chose to prohibit the construction of any new industries or educational and research institutions. The emphasis was on creating housing and service facilities for the residing population:

[The general plan] is a grand program of further development and reconstruction of the city that will provide the best conditions for work, life, and recreation, high satisfaction of their everyday needs. (Kamenskii and Naumov 1966:6, emphasis added)

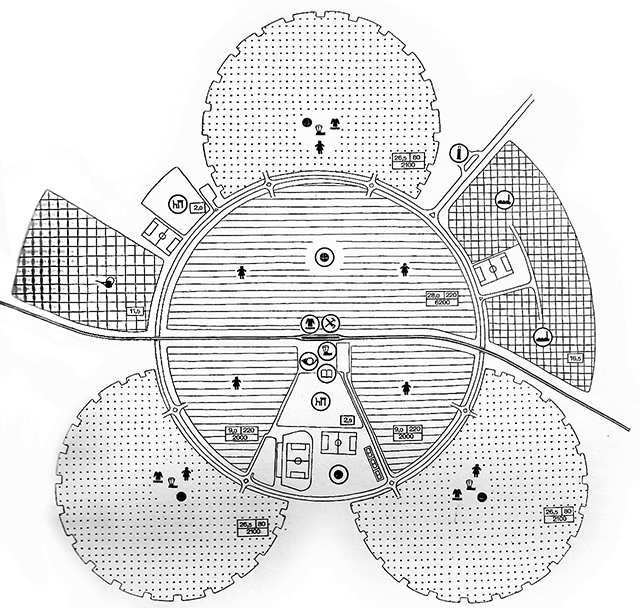

A substantial increase in housing provision—from 25.8 to 50 million square meters—was planned for large yet compact prefabricated housing districts in empty territories (within the current borders of the city), taking natural conditions, work possibilities, and commuting into account. In this project, microdistricts (mikroraiony) became the basic planning unit for construction, aiming to create a comprehensive infrastructure of accommodation and social amenities, complemented by a system of public transport:

The planning structure of the microdistrict provides for a comfortable, within 500 meters, allocation of services, functional zoning of territories (housing, schools, preschools, garden, and sport center), and isolation of buildings from negative [environmental] effects of public transport…. School becomes one of the core planning elements and determines the size of the microdistricts, informed by the normative idea that children should not be deprived of family influence [which occurs if they are forced to spend a lot of time commuting between school and work]. (Proekt general’nogo plana 1964:67)

A strong emphasis on the development of social infrastructure and collective consumption was made in the presentation of future plans for the period 1966–1990. One of the main ideological premises of the planned economy was an inevitable increase in wellbeing as a result of “decreased working time, increased free time, and increased need for recreation” (Kamenskii and Naumov 1966:11). Therefore, the development of public services was symbolically important, and the plan specified exact numbers of various facilities per 1,000 inhabitants (places in preschools and schools, hospitals, work opportunities in shops, and square meters of sports facilities): “All facilities planned for everyday use are recommended to be allocated close to dwellings … or partly inside dwellings. The overall territory [allocated for such facilities] will amount to ten sq. meters per dweller” (Proekt general’nogo plana 1964:67, 69). Although territorial development was limited to the city’s boundaries, an increase in the capacity of public transportation was planned as a key element in implementing the principle of social settlements—namely, shorter distance between workplace and place of residence.

The second goal of bringing the city closer to the Gulf of Finland had an aesthetic (creating an impressive architectural composition), practical (further development of the sea transportation route), and social (giving residents the opportunity to enjoy the sea view and various recreational facilities) premises. As mentioned above, the objective of improving the living standards by means of developing suburban areas as residential districts, nature preserves, and healthcare institutions was very pronounced. Apart from that, integration of the surrounding region into the general layout of the city would contribute to creation of a joint labor force, connecting the center and periphery into a coherent territory.

Stockholm (1999)

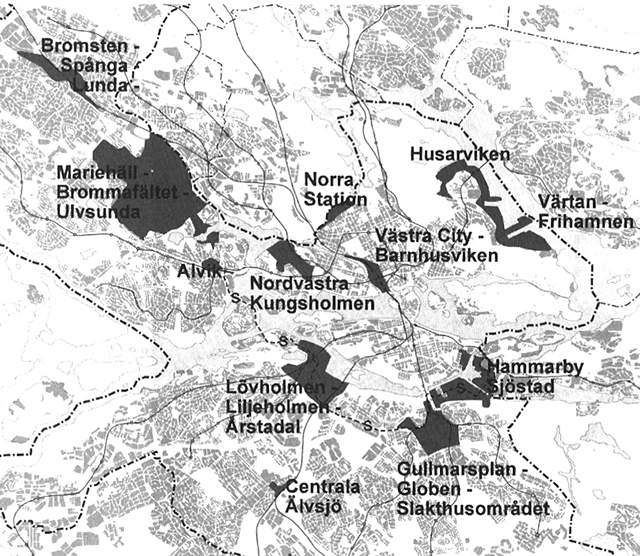

Urban development and housing policy had a central role in the shaping of the Swedish welfare state. Spatial development demanded extensive coordination of efforts to bring together laws, policy areas, regulations, and subventions to create the “social democratic city.” When the 1999 plan was launched, several preconditions for planning had changed since the 1950s: above all, the prospects and the support for centralized city planning had decreased both in academic and public debates, something that is evident throughout the plan itself. As a result, the plan of 1999 had a less extensive format and its content was of a more general nature. The plan was divided into two broad sections: the first one comprised conditions and strategies for outline planning, while the second provided guiding principles for land use, development of settlements, construction, green areas, and areas of cultural-historical value. The overreaching goals included: 1) using the advantages of the Stockholm region; 2) meeting the demand for transformation and dynamism; 3) developing and making use of the quality and character of the city; 4) promoting employment, welfare, and social balance; and 5) ensuring a sustainable society (Översiktsplan 1999 Stockholm:16).

The current plan is significantly different from the general plan of 1952. The first three established goals are implicitly intertwined and emphasize the unique place Stockholm holds among European cities, described in terms of the city’s beauty and cultural heritage but also, to a lesser extent, the possibilities for a comfortable everyday life. It promotes the idea of increasing the city’s attractiveness to tourists by arranging large-scale international events and spectacular architectural innovation. The role of Stockholm in the Baltic Sea region was especially accentuated: “changes in Eastern Europe result in the fact that earlier historical relations and economic connections with the Baltic countries and Russia can be rediscovered, grown, and strengthened” (Översiktsplan 1999 Stockholm:14–15). An intensification of relations with the rest of Europe through Sweden’s membership in the European Union was directly illustrated through the launching of the “European city” concept[4] and its actions for developing sustainable cities.

Economic growth and the different strategies to increase the attractiveness of the city have gained a more pronounced focus. The social aspect, which in the earlier plan was central, now has a more peripheral position. The issue of residential segregation is put forward as a concern, although the focus on good and affordable housing for all, prominent in the earlier plan, no longer characterizes the strategy for future development and building. Instead of promoting common standards, the plan stresses the existence of and desire to satisfy the diverse requirements of citizens from different social groups. It distinguishes the special interests of citizens with precarious patterns of residence (homeless, young, divorced, etc.) who are in need of affordable housing, those who have the means to acquire higher standards of living, and those who are situated in immigrant-dense areas. As a way of meeting these diverse demands, the construction of new high-quality (and high-cost) housing should initiate “chains of migration” (flyttkedjor) within the city—those who can afford the new expensive housing would vacate their old residences for the less privileged (Översiktsplan 1999 Stockholm:32–34).

A striking difference between the main principles for production of urban space is demonstrated by the abandonment of the idea of the possibility of steering city development by means of planning in general:

… physical planning is not a means of governing in the sense that it can force a development in a desired direction or guarantee that measures in fact will be realized. Those driving forces in the society, those “many invisible hands” that are decisive for the city’s vitality, as well as changes in business, technology, and international economy, are situated outside the sphere of competence of both state and individual communities. (Översiktsplan 1999 Stockholm:5)

“Globalization,” “open and active planning,” and “future scenarios” are newly introduced concepts that illustrate a new turn in contemporary urban planning in Stockholm.

Saint Petersburg (2005)

During the forty years following the discussed plan for Leningrad, the city did not simply change its name; the strategy of urban development had undergone a drastic reconsideration, reflected in the most recent general plan of 2005. First, the plan was accepted at the level of the city’s Legislative Assembly in the form of a law for the first time in the city’s history. Previously, city development was not regulated by law but by subordinate regulations. According to Vladimirov (2003), the socialist command system of administration did not require more comprehensive regulatory mechanisms. The new approach to city planning included other social and economic actors, such as municipalities and private entrepreneurs, and required an explicit legislative framework and technocratic presentation.

Second, objectives and priorities were revised in the light of new social, political, and economic realities. The plan begins with two general goals: 1) to ensure stable improvement of the living standards of all groups of the population (with orientation toward European standards) and 2) to integrate the city into the Russian and world economy as a multifunctional city providing a high quality environment for living and production, strengthening the role of the city as a center in the Baltic Sea region and northwest of Russia.

Two important aspects in interpreting the desired living standards can be mentioned here: the idea of restricting the size of the city’s population was abandoned and the persistent references to “European standards”—in formulating indicators for development of housing, social, and healthcare provision as well as recreation facilities—was not accompanied by an explanation of what those standards actually constitute. The projected growth of the population through incoming migration was justified by a need to compensate for negative demographic tendencies (decreased fertility, increased mortality, and outgoing migration) and to ensure an adequate supply of labor. Housing provision is prioritized as one of the most urgent and effective means of reaching this goal:

An increase in the quality of life of citizens of Saint Petersburg with the aim to achieve average European standards, above all things in terms of providing them with housing space no less than 35 sq. meters per person by 2025; increase in the number of organizations of social sphere (healthcare, education, sports, social protection, etc.) up to the standard level of the Russian Federation and average European level. (Zakon Sankt-Peterburga No. 728-99 2005, section 2.1 “Goals of the Territorial Planning of Saint Petersburg”)

Similar to the earlier references to the standard of living in socialist settlements, the recurring ideal of “European standards” is very abstract and somewhat ad hoc: what is defined as prospective outcomes in the plan is to be considered an international standard. An important innovation in the concept of city space is the recognition and embrace of diversity, both in terms of the above-mentioned standards of living, economic practices, and overall territorial organization. Extensive plans for renovating and transforming dilapidated and crowded housing as well as constructing new, high-quality housing still focused on large, prefabricated apartment complexes. However, individual construction is expected to grow substantially: by 2025, the share of housing space in the form of single-family houses was expected to be larger than the share of apartment estates (3.7 and 3.3 square hectares respectively). Although all neighborhoods, irrespective of forms of construction, were supposed to be integrated into the city’s infrastructure, “diversification of residential environment and used [construction] materials, construction forms and planning solutions in accordance with the diversity of urban conditions” was also expected to satisfy the diverse needs of various social groups (Zakon Sankt-Peterburga No. 728-99 2005, section 2.2 “Targets of the Territorial Planning of Saint Petersburg”).

The idea of Saint Petersburg’s special status as both an “open European city,” attractive to international tourism and investments, and an important national megalopolis was a veritable refrain through the whole plan. The goal of creating a new image of the city, oriented towards the Baltic Sea region and the European Union, aimed to integrate it into the international economic and political system, especially as a nodal point for shipping and land routes. As a consequence, strong emphasis was put on the development of new business areas. Territorial planning was expected to follow projections for economic development, which is no longer centrally planned and increasingly diversified, as a means of increasing the city’s attractiveness to new investors and inhabitants.

Bringing Ideologies to Life

We started this study with the aim of illustrating how the process of city planning can be viewed as a part of a larger ideological project. Differences in the plans’ presentation and the level of their detail make direct comparison challenging. It is, nevertheless, possible to conclude that the change in the political and ideological environment had a direct and predictable effect on the representations of space in the planning documents and what transformations to space were accepted. Our comparative analysis reveals some important similarities and differences.

First, although the intensive construction of socialism in Russia and social democracy in Sweden were underpinned by the same strong focus on equality, homogeneity, and cohesion, the general planning objectives were specified very differently, with starkly contrasting understandings of the role of population size in the future equality project. The Soviet ideology of space conceived of urbanization as initially uneven, and, therefore, the distribution and location of industries and labor force should be controlled in order that “old” urban areas (like Leningrad) would not continue growing (Seniavskii 2003). In Sweden, the production of spatial ideology was integrated into the project of welfare state construction, with a much stronger emphasis on redistribution, through social security “from the cradle to the grave,” as a key instrument in equalization of life and opportunities (Khakee 2003).

The notion of an encompassing state responsibility for citizens’ welfare was equally important to both approaches, but while Soviet planners could expect direct coercion in the process of implementing of their objectives, Swedish planning scenarios were to be realized in a more open manner, albeit strictly supervised and in cooperation with private actors. The significant and pronounced retreat of the idea of equality that followed transformations in both countries in the late 1980s undermined the distribution of resources as a mechanism for achieving wellbeing. Letting go of the notion of providing for equality through spatial organization also precludes the possibility of imposing norms of social conduct. Nevertheless, the conviction that space can and should be planned was reflected in the degree of precision with which the planning indicators were presented in the earlier plans, allowing for subsequent control of their realization. This approach would be incompatible with the more recent orientation toward flexibility of methods and attraction of capital to participate in the dynamic creation of space.

The planning strategy aimed at unifying and equalizing the physical environment in the Soviet Union has been criticized for producing a poor aesthetic culture (Cooke 1997), failing to solve the housing shortage, and strengthening rather than eliminating inequalities in access to housing (Bessonova 1992). In Sweden, the neighborhoods launched under the 1952 plan, especially the ones built during the Million Dwellings Program (Miljonprogrammet), have been criticized in professional, academic, and public debates for being too uniform, too large-scale, and even as “no-go” areas reserved for society’s least privileged (Hall and Vidén 2005). Although these are valid and important observations, a less-often discussed element of the spatial organization embedded in the planning is the normative control of everyday life. In Sweden, it was rooted in the notion of the Swedish “people’s home” (folkhemmet)[6] and the conception of the city as an organism with the division between “the others” and “us.” The city planning and housing policy has been a technology for disciplining and normalizing “the others” through residence patterns. The objective of equality, in this sense, included perceptions of “sameness” and therefore contained practices of exclusion (Molina 1997). In Russia, the regulation of everyday practices was grounded in a problematization of the domestic realm and strong normative notions of good and bad practices (not just bad taste, as Buchli [1997] asserted). Space is not the only thing that is allocated when the city’s economic and political structure takes shape; the activities such as child raising, consumption, leisure, and so on to be carried out in that physical environment are also planned. The sanctioning of individual behavior is realized by making deviant practices uncomfortable or impossible—a disciplining policy that was developed and successfully employed decades earlier (Meerovich 2008). The critique of city planning in Sweden and the Soviet Union during this time follows the line of a more general critique of postwar modernistic planning as such (see for example Jacobs [1961]). This critique also emphasizes the common influences with regard to spatial representations in different systemic contexts.

Second, as the rhetoric of both contemporary plans aspires to create a comfortable urban environment, equality, no longer a prerequisite of successful economic development and progress, is still present in the planning discourse and considered as a result of innovative marketing and investments—an adjustment to the demands and opportunities of the market. This finding is not surprising in the light of recent global socioeconomic, political, ideological, and spatial restructurings, which have made cities and urban regions into denationalized platforms for economic and symbolic power in the new global economy (Castells 1996; Friedmann 2002). It is especially important to note that the political, economic, and social changes that accompanied these parallel ideological shifts were not equally dramatic. While the Russian transformation was radical, the retrenchment of the Swedish welfare state was more subtle but nevertheless undeniable (Hort 2009).

In the last two decades both Stockholm and Saint Petersburg employed various strategies to enable and enhance their competitiveness in the global arena, which can be related to the global phenomenon of the “entrepreneurial city” (Golubchikov 2010; Harvey 1989). Both cities are also involved in interregional cooperation—for example through the EU Strategy for the Baltic Sea Region—and comply with EU efforts in urban/regional development (European Commission 2008). A feature of this strategy is that while promoting spatial homogenization and coherence, it supports urban/regional entrepreneurship that consequently leads to competition and a “trickle-down effect,” where the outcome is expected to benefit all of society.

These formulations of standards for future development (the European city, the global city) are open for interpretation depending on national preconditions, but are largely based on external models. Earlier research related the construction of the ideal of the “European city,” with its local idiosyncrasies, to the notion of the “American city,” with its uniformity (Molnar 2010), referring to aesthetic but also social and historical distinctiveness. While for Stockholm the notion of the “European city” is developed to stimulate marketing strategies and capitalizing on “local idiosyncrasies” in an era of global competition between cities, Saint Petersburg is being reinvented and reestablished as one more European city among peers. Instead of competing, the current plan for Saint Petersburg is struggling to ascertain commonalities in order to overcome its former separation from the European community. The shift that took place in both contexts, exemplified by the notion of the European city, unveils a normative perception of commodified urban space, in strong contrast to the earlier focus on urban inhabitants and their standards of living. The principle of centralized top-down steering has been replaced by a globalized agenda-setting approach, which only can be realized at the local level.

To summarize, economic, political, and ideological restructuring has changed the understanding of planning practice as means of transforming the fabric of urban space, restricted planners’ room to maneuver, and simultaneously increased the state’s need to legitimate planning (Young 2008:75). While in the earlier plans space was conceptualized as “plannable,” a means of centralized manipulation of social development toward a desired direction, contemporary plans transfer some control over space to the market and underscore the need for continuous flexibility and adjustment. As a result, space in general becomes conceptualized as “unplannable,” not subject to direct top-down control; instead, the formulation of spatial representations and organization of the planning process becomes open to other actors, creating new conditions for planning without the centralized state control. The resultant unpredictability of representations of space needs to be incorporated into plans. In reaction to this challenge, the plan for Saint Petersburg included a special projection for which laws would need to be passed by the city’s legislative bodies in order to structure relationships among different actors, such as government, investors, entrepreneurs, and citizens. The Stockholm plan became less precise in its orientation, creating opportunities for regular revisions and adjustments without reconsideration of the overall concept. Social engineering within the capitalist economy of today is, as much as in other systems, based on ideological prerequisites that should not be overlooked. General city plans are much more similar in promoting global neoliberal goals than in projecting equality goals.

Concluding Remarks

With regard to contemporary trends in urban development, neoliberalism is usually presented by politicians in the public debate as the only alternative for a postindustrial society, where different forms of interventions and regulations are designed to create the best conditions for expanding market adaptation. Here, we do not discuss whether all changes to planning ideas took neoliberal forms but instead concentrate on the foundational principles that follow the trend to extend “market discipline, competition, and commodification throughout all sectors of society” (Brenner and Theodore 2002:3).

In our analysis of city planning in Saint Petersburg and Stockholm, this becomes most evident through examining the shift in conceptualizations of space—from “plannable” to “unplannable”—during the two time periods. A critique of the disciplining aspects of former centralist bureaucratic conceptualizations of space is evident in the scholarship, but “the disciplining order of the market or of non-state social forces is more rarely subjected to the same attention, hiding its power behind the love affair with chaos” (Massey 2005:112). This article aims, through historical comparison, to contribute to the unmasking of ideological norms and ideals behind the current transformation of spatial representations. The shift in conceptions of space signifies the abandonment of ideas that presented an alternative to market-based societal development. In line with the notion of globalization, this illustrates the hegemonic status of neoliberal ideology and its influence on urban planning.

This, of course, is not to imply that homogenization of the ideological underpinnings of urban planning leads to the same outcomes in every national context—this deserves a study of its own—but our analysis of changes in city planning in two cities, Saint Petersburg and Stockholm, testifies to a certain convergence toward a uniform postindustrial, in other words neoliberal, “global” city.

References

- Allen, John and Michael Pryke. 1994. “The Production of Service Space.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 12(4):453–475.

- Bessonova, Olga. 1992. “The Reforms of the Soviet Housing Model: The Search for a Concept.” Pp. 220–230 in The Reform of Housing in Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union, edited by Bengt Turner, József Hegedus, and Iván Tosics. London: Routledge.

- Brenner, Neil. 2004. New State Spaces: Urban Governance and the Rescaling of Statehood. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Brenner, Neil. 2009. “What Is Critical Urban Theory?” City 13(2–3):198–207.

- Brenner, Neil and Nik Theodore. 2002. “Cities and Geographies of Actually Existing Neoliberalism.” Pp. 2–32 in Spaces of Neoliberalism: Urban Restructuring in North America and Western Europe, edited by Neil Brenner and Nik Theodore. Malden, MA: Blackwell.

- Brown, Kate. 2001. “Gridded Lives: Why Kazakhstan and Montana Are Nearly the Same Place.” The American Historical Review 106(1):17–48.

- Buchli, Victor. 1997. “Khrushchev, Modernism, and the Flight against Petit-Bourgeois Consciousness in the Soviet Home.” Journal of Design History 10(2):161–176.

- Castells, Manuel. 1996. The Information Age: Economy, Society, and Culture. Vol. 1, The Rise of the Network Society. Malden, MA: Blackwell.

- Cooke, Catherine. 1997. “Beauty as a Route to the ‘Radiant Future’: Responses of Soviet Architecture.” Journal of Design History 10(2):137–160.

- European Commission. 2008. Green Paper on Territorial Cohesion: Turning Territorial Diversity into Strength, COM (2008) 616, October. Retrieved September 29, 2013 (http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=COM:2008:0616:FIN:EN:PDF).

- Fainstein, Susan S. 2000. “New Directions in Planning Theory.” Urban Affairs Review 35(4):451–478.

- Flyvbjerg, Bent. 2003. “Rationality and Power.” Pp. 318–329 in Readings in Planning Theory, edited by Scott Campbell and Susan S. Fainstein. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Franzén, Mats. 2004. “Rummets tvära dialektik: Notater till Henri Lefebvre.” Pp. 49–63 in Urbanitetens omvandlingar: Kultur och identitet i den postindustriella staden, edited by Ove Sernhede and Thomas Johansson. Göteborg, Sweden: Daidalos.

- Franzén, Mats and Eva Sandstedt. 1981. Välfärdsstat och byggande: Om efterkrigstidens nya stadsmönster i Sverige. Lund, Sweden: Arkiv.

- French, Anthony R. 1995. Plans, Pragmatism and People: The Legacy of Soviet Planning for Today’s Cities. Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh Press.

- Friedmann, John. 2002. The Prospect of Cities. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Friedmann, John. 2005. “Globalization and the Emerging Culture of Planning.” Progress in Planning 64(3):183–234.

- Gans, Herbert J. 2002. “The Sociology of Space: A Use-Centered View.” City and Community 1(4):329–339.

- Generalplan för Stockholm. 1952. Stockholm: Stockholms stadsplanekontor.

- Golubchikov, Oleg. 2004. “Urban Planning in Russia: Towards the Market.” European Planning Studies 12(2):229–247.

- Golubchikov, Oleg. 2010. “World-City-Entrepreneurialism: Globalist Imaginaries, Neoliberal Geographies, and the Production of New St Petersburg.” Environment and Planning A 42(3):626–643.

- Gottdiener, Mark and Joe R. Feagin. 1988. “The Paradigm Shift in Urban Sociology.” Urban Affairs Review 24(2):163–187.

- Gunder, Michael. 2005. “The Production of Desirous Space: Mere Fantasies of the Utopian City?” Planning Theory 4(2):173–199.

- Hall, Peter. 1999. Cities in Civilization: Culture, Innovation, and Urban Order. London: Phoenix Giant.

- Hall, Stefan and Sonja Vidén. 2005. “The Million Homes Programme: A Review of the Great Swedish Planning Project.” Planning Perspectives 20(3):301–328.

- Harvey, David. 1985. The Urbanization of Capital: Studies in the History and Theory of Capitalist Urbanization. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Harvey, David. 1989. “From Managerialism to Entrepreneurialism: The Transformation in Urban Governance in Late Capitalism.” Geografiska Annualer 71(1):3–17.

- Healey, Patsy and Richard Williams. 1993. “European Urban Planning Systems: Diversity and Convergence.” Urban Studies 30(4–5):701–720.

- Herington, John. 1989. Planning Processes: An Introduction for Geographers. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Hort, E. O. Sven. 1990. Social Policy and Welfare State in Sweden. Lund, Sweden: Arkiv.

- Hort, E. O. Sven. 2009. “The Swedish Welfare State: A Model in Constant Flux?” Pp. 428–443 in The Handbook of European Welfare Systems, edited by Klaus Schubert, Simon Hegelich, and Ursula Bazant. London: Roudledge.

- Jacobs, Jane. 1961. The Death and Life of Great American Cities. New York: Random House.

- Kamenskii, Valentin. 1972. Leningrad: General’nyi plan razvitiia goroda. Leningrad: Lenizdat.

- Kamenskii, Valentin and Aleksandr Naumov. 1966. General’nyi plan razvitiia Leningrada. Leningrad: Stroiizdat.

- Khakee, Abdul. 2003. “Den post-socialdemokratiska staden är här.” Plan: Tidskrift för samhällsplanering 57(1):40–43.

- Klosterman, Richard E. 1985. “Arguments for and against Planning.” Town Planning Review 56(1):5–20.

- Kogan, Leonid. 1982. Sotsial’no-kul’turnye funktsii goroda i prostranstvennaia sreda. Moscow: Stroiizdat.

- Leary, Michael E. 2009. “The Production of Space through Shrine and Vendetta in Manchester: Lefebvre’s Spatial Triad and the Regeneration of a Place Renamed Castlefield.” Planning Theory and Practice 10(2):189–212.

- Lefebvre, Henri. 1991. The Production of Space. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Mandelbaum, Seymour J. 1990. “Reading Plans.” Journal of the American Planning Association 56(2):350–356.

- Marcuse, Peter and Ronald van Kempen. 2000. Globalizing Cities: A New Spatial Order? Oxford: Blackwell.

- Massey, Doreen. 2005. For Space. London: Sage Publications.

- Meerovich, Mark. 2008. Nakazanie zhilishchem: Zhilishchnaia politika v SSSR kak sredstvo upravleniia liud’mi, 1917–1937. Moscow: RosPEn.

- Molina, Irene. 1997. “Stadens rasifiering: Etnisk boendesegregation i folkhemmet.” PhD Dissertation, Department of Human Geography, Uppsala University.

- Molnar, Virag. 2010. “The Cultural Production of Locality: Reclaiming the ‘European City’ in Post-Wall Berlin.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 34(2):281–309.

- Översiktsplan 1999 Stockholm. Stockholm: Strategiska avdelningen, Stadsbyggnadskontoret.

- Perry, David. 1995. “Making Space: Planning as a Mode of Thought.” Pp. 209–242 in Spatial Practices: Critical Explorations in Social/Spatial Theory, edited by Helen Liggett and David Perry. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Proekt general’nogo plana Leningrada 1958–1980. 1964. Tsentral’nyi gosudarstvennyi arkhiv nauchno-tekhnicheskoi dokumentatsii Sankt-Peterburga. F. 386. Op. 3-3. D. 35.

- Ruble, Blair A. 1990. Leningrad: Shaping a Soviet City. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Ruoppila, Sampo. 2007. “Establishing a Market-Oriented Urban Planning System after State Socialism: The Case of Tallinn.” European Planning Studies 15(3):405–427.

- Scott, James W. 1992. The Challenge of the Regional City. Berlin: Dietrich Reimer Verlag.

- Seniavskii, Aleksandr. 2003. Urbanizatsiia Rossii v XX veke. Moscow: Nauka.

- Taylor, Nigel. 1998. Urban Theory since 1945. London: Sage.

- Vladimirov, V. 2003. Regional’noe gradostroitel’noe planirovanie. Saint Petersburg: Limbus Press.

- Yiftachel, Oren. 1998. “Planning and Social Control: Exploring the Dark Side.” Journal of Planning Literature 12(4):395–406.

- Young, Greg. 2008. “The Culturization of Planning.” Planning Theory 7(1):71–91.

- Zakon Sankt-Peterburga No. 728-99. 2005. “O general’nom plane Sankt-Peterburga i granitsakh zon okhrany ob’’ektov kul’turnogo naslediia na territorii Sankt-Peterburga.” Retrieved September 29, 2013 (http://ppt.ru/newstext.phtml?id=4560).

- Zukin, Sharon. 1995. The Cultures of Cities. Oxford: Blackwell.

Разочарование в «грандиозных планах»? Репрезентации пространства в практике городского планирования в России и Швеции

Лиза Кингс – исследователь в Институте по изучению миграции, этничности и общества (REMESO) в Университете Линчёпинга и старший преподаватель Школы социальных наук Университета Сёдерторна. Адрес для переписки: School of Social Sciences, Södertörn University, ME241, SE-141 89, Huddinge, Sweden. lisa.kings@sh.se.

Жанна Кравченко – старший преподаватель факультета социологии Университета Уппсалы и исследователь в Школе социальных наук Университета Сёдерторна. Адрес для переписки: Department of Sociology, Uppsala University, Box 256, 751 05, Uppsala, Sweden. zhanna.kravchenko@soc.uu.se.

Исследование, о котором идет речь в этой статье, было осуществлено при поддержке Фонда Балтийского моря, Университета Сёдерторна и факультета социальных наук (Школа социальной работы) в Университете Лунда. Авторы выражают особую благодарность трем анонимным рецензентам и редакторам Laboratorium за их глубокие и конструктивные замечания и предложения.

В статье изложены результаты исследования репрезентации городского пространства в ходе городского планирования в Стокгольме и Ленинграде/Санкт-Петербурге за последние полвека. Городские генеральные планы, которые представляют собой эмпирическую основу статьи, были претворены в жизнь в периоды, весьма значимые для исторического развития обеих стран, – в середине ХХ века и в начале ХХI-го – и отражают специфику их идеологического и социально-политического наследия. Статья описывает, каким образом репрезентации пространства, представленные как идеи о целях и возможностях пространственного планирования, изменялись с течением времени, и как они отражали общие политические, экономические и идеологические преобразования в Швеции и России. Две основные темы представлены в анализе. Во-первых, идеал равенства, который доминировал как в социалистической, так и социал-демократической идеологии в 1950–1960-х годах и благодаря которому были открыты возможности для широкого нормативного контроля и манипулирования общественной жизнью посредством планирования физической среды. Во-вторых, идеал «Европейский/глобальный» город, который выделяется как средство содействия экономическому развитию путем включения новых акторов и переключения на более рыночно-ориентированный подход к планированию в начале 2000-х годов.

Ключевые слова: городское планирование; репрезентация пространства; Стокгольм; Санкт-Петербург

- Although the term “master plan” is used more often in relation to this type of documents, this study uses “general plan” as a category that is semantically close to categories used in respective languages: генеральный план in Russian and generalplan in Swedish (before 1987). ↩

- Both the previously classified project for the general plan accepted in 1962 and the publicly available version of the plan from 1966. Considering that general city plans were not publicly available during the Soviet period, three versions of the plan’s text were examined in order to capture representations targeted at both professional and general public. ↩

- The 1952 general plan for Stockholm includes a nineteen-page summary in English. ↩

- A concept related to the engagement in EU and OECD of the future of urban environment and the development of European sustainable cities. Focus is on cultural, aesthetic, and environmental aspects, but the need for flexibility of cities is also of special concern. ↩

- Source: Attachment 2 to Zakon Sankt-Peterburga No. 728-99 2005. ↩

- A social democratic idiom from the 1930s for the expanding welfare state. ↩