Russian Pension Reform: Why So Little Engagement from Below?

© Laboratorium. 2017. 9(3):44–69

Aadne Aasland is a Senior Researcher at Norwegian Institute for Urban and Regional Research. Address for correspondence: NIBR, Oslo and Akershus University College of Applied Sciences, PO Box 4, St. Olavs Plass, 0130 Oslo, Norway. aadne.aasland@nibr.hioa.no.

Linda J. Cook is Professor of Political Science and Slavic Studies at Brown University. Address for correspondence: Department of Political Science, Brown University, Box 1844, 36 Prospect Street, Providence, RI 02912, USA. linda_cook@brown.edu.

Daria Prisyazhnyuk is a Senior Lecturer at the National Research University–Higher School of Economics. Address for correspondence: National Research University–Higher School of Economics, ul. Miasnitskaia 20, Moscow, 101000, Russia. daria.prisyazhnyuk@hse.ru.

This article analyzes influences on the post-2012 Russian pension reform, focusing on influences “from below.” We identify four main controversial issues related to pension reform: changes in individual accumulative accounts, financing of the system, age of pension eligibility, and indexation of pensions to compensate for inflation. The article uses an analytical framework for understanding welfare reforms developed by Tone Fløtten that we employ to identify four sets of influences on Russian pension reform: from above (high-level decision makers), inside (state bureaucracy and professionals), outside (international organizations and policy learning), and below (civil society and public opinion). We argue that the reform has been driven by elites from above and inside who have largely protected the interests of current and near-term pensioners. Costs have been imposed mainly on current workers and future pensioners. The core of the article focuses on influence from below and presents data from public opinion polls about pension reform, the positions and influence of pensioners’ and other societal organizations, and the near absence of protest. We argue that maintenance of current pensioners’ incomes, deferral of costs into the distant future, and the complex and often obscure nature of the reforms account for the lack of pushback from below. While Russian civil society remains weak, citizens have protested loss of social rights in other arenas. Our article explains the lack of societal engagement or protest in response to this major reform. The article is based on analysis of newspaper articles, civil society organizations’ webpages, and academic and policy documents in Russian and English. The document analysis has been supplemented with 12 semistructured interviews with a range of pension reform experts.

Keywords: Pension Reform; Russia; Civil Society; Public Opinion; Protest

At the end of 2013 the Russian State Duma adopted three pension laws that represented a major overhaul of Russia’s pension system.[1] The reform was motivated by increasing Pension Fund deficits, an economic downturn of the Russian economy, and ageing of the population.[2] Its main purpose was to cut expenditures and budget subsidies to the pension system in the short term and to increase the system’s long-term viability. The reform introduced a new pension formula that takes into account the number of years worked, the salary during those years, and the age of retirement, benefitting those who continued to work after the official retirement age. The accumulative (or funded) component of the pension system that had been introduced with the major pension reform in 2002 became voluntary.

While in recent months and years there have been mass protests against planned and implemented pension reforms around the world, in particular in some Latin American countries,[3] Russian civil society has remained conspicuously silent. No major demonstrations against the reforms have been organized, nor have organizations representing pensioners protested reforms. This response is also in stark contrast to the nationwide protests that erupted when the regime introduced monetization of social benefits to try to reduce the social burden on the state in 2005. Those protests demonstrated the strong mobilization capacities of pensioners and halted the government’s efforts at rationalization of the benefits system (Cook 2007:179–182). While the 2005 protests stand alone as national-level mobilizations against social entitlement cuts in the era of President Vladimir Putin, localized protests over loss of social rights (in housing, education, health care) have increased during the current recession (Greene 2014:145–166; Holm-Hansen 2016). So, how has Russia’s government managed to reduce the burden of pensions without provoking societal opposition?

We discuss several plausible explanations for the low level of activity from below intended to influence the direction of pension reform. We use an actor-oriented analytical framework to frame and assess different types of influences. Three factors are emphasized: the complexity and opaqueness of the reform itself, the well-known weakness of Russian civil society, and the substance and effects of the reforms that were enacted. Moreover, we examine how civil society organizations, including those representing pensioners, trade unions, employers, and veterans, viewed pension reforms.

To preview the argument: we find that current and near-term pensioners, who have the strongest stake in the system and demonstrated capacity for mobilization, were largely protected from both declines in the real value of their pensions and increases in the pension eligibility age. Indeed, payments to current pensioners have been maintained partly by taking current workers’ contributions in accumulative accounts and using them to sustain current pension levels. In principle, these contributions are to be returned to the accounts, and in any case affected workers will not feel these losses for decades. Increases in the age of pension eligibility, while viewed as a necessity by elites and pension specialists, have been delayed indefinitely.[4] In sum, the reform avoids imposing immediate costs on current recipients and, thus, averts both blaming of politicians and societal pushback. The complex and confusing reform process—and an environment of economic volatility and uncertainty—also discourage public engagement. The weakness of relevant civil society actors is also a contributing factor.

Despite a relatively large number of societal organizations, Russia is well known to have a weak and state-dependent civil society. Earlier scholarship (e.g., Evans, Henry, and Sundstrom [2006] 2016) shows a civil society that is fragmented, lacks information and organizational resources, a broadly authoritative nation-wide leadership, and a platform for joining forces to work out collective demands. Since 2006 NGOs have been placed under increasing state restrictions and surveillance (Ljubownikow, Crotty, and Rodgers 2013:161–163; Flikke 2016). A sense of solidarity among different segments of the population is also in short supply. In many Western countries trade unions have played a major role in influencing the course of pension reforms and sometimes even exerted a veto power on the introduction of reforms that they disapprove (Ebbinghaus 2011). The Russian trade union movement, however, is weak, which prevents it from acting as a bargaining agent for labor (Vinogradova, Kozina, and Cook 2015; Davis [2006] 2016).

The tougher formal and informal sanctions against labor strikes and civic protests, in particular after mass political protests in 2011–2012, are yet another obstacle to public engagement and civil society activity. As research from Graeme B. Robertson’s authoritative study of protests in 1997–2000 shows, most protests have focused on social issues that are concrete, particularistic, and local (2010:49–63). Recent protests that have erupted when communities are threatened with the loss of long-held social benefits follow this model. Policies of both repression and cooptation of civil society organizations during Putin’s third term as president have represented an additional obstacle to more independent public engagement and civil society activity on the pension issue.

The article proceeds as follows: We first present the analytical framework and the data sources for our study. The second section presents a brief historical background and explains the most contentious issues of the ongoing pension reforms. The third part looks at “influence from below” through the lenses of public opinion, activities of civil society organizations, and protests. We then return to explaining “why so little pressure from below,” in light of broader accounts of welfare state retrenchment.

Framework for analysis and data sources

In contemporary Russia, federal policy making, on pensions as well as many other areas, is dominated by the presidential administration and relevant central ministries. While some areas of welfare have been decentralized to the regional level, the pension system remains the sole responsibility of the federal government (Kulmala et al. 2014:529). Despite its domination by federal authorities, however, the pension reform affects many societal stakeholders who are consulted in various forms in the policy process. Paul Pierson (1994) has argued that welfare programs create constituencies in society, including beneficiaries, professional organizations, and public sector workers, who have a vested interest in the existing system and usually resist reform. Following this analysis, we analyze how and how much societal stakeholders may impact the policy process. Besides pensioners’ organizations, our study includes private business, employers’ associations, and trade unions, as well as think tanks and academic institutions.

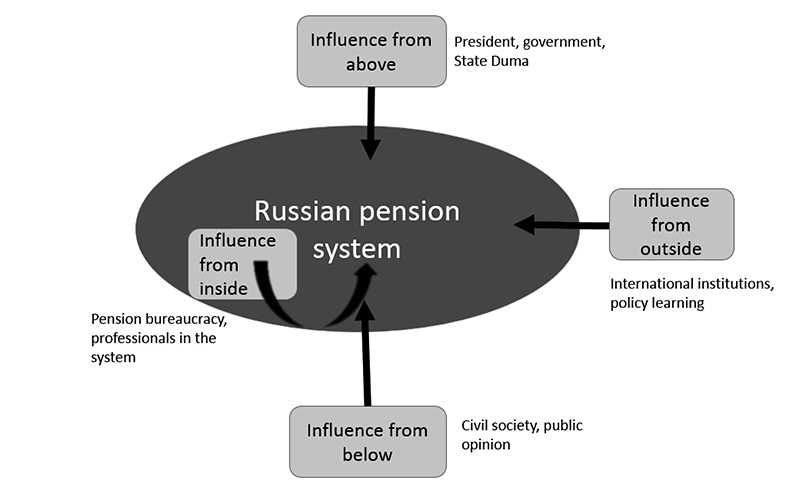

We rely on Tone Fløtten’s (2006) model of quadruple pressure to structure the study of societal stakeholders’ influence on policy outcomes but use the broader concept of “influence” instead of Fløtten’s more narrow “pressure.” The model, shown in Figure 1, identifies four types of influence on policy reform processes: from above, inside, outside, and below. Analysis of the reforms using this quadruple model provides a comprehensive view of all significant stakeholders and helps to identify not only sources of influence but also crosscutting pressures and the composite roles of actors.

Our main concern in this article is influence “from below,” including public opinion and organized protests as well as civil society involvement. We also pay some attention to how policy elites structured the reform, because this is key to an understanding of the societal response. A separate article fully analyzes the other three sets of influences (Cook, Aasland, and Prisyazhnyuk forthcoming). By “above” we understand the ruling elites: the president, the ministers responsible for the reform, the ruling United Russia (Edinaia Rossiia) Party, and the State Duma. “Inside” is defined as the ministerial bureaucracies, the state Pension Fund, private pension funds, and other actors with significant professional interest in the issue. By influence from “outside” we have in mind advice from foreign countries and international organizations, such as the World Bank, International Monetary Fund, Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, and others, as well as policy learning from foreign pension reform experience.

These influences should not be considered mutually exclusive, as some actors may belong to more than one category. In fact, we find in Russia networking among all four categories of actors and collaboration to strengthen pressure for shared goals (Aasland, Berg-Nordlie, and Bogdanova 2016:148–149). Mass media also plays a role, although not as an independent actor. Rather, various media provide platforms that give voice to actors with different agendas and forms of influence. In sum, we use Fløtten’s model as an analytical tool to study how these various actors engage with and try to influence pension reforms in Russia and whether they succeed or fail. The model should not be considered static, as the continuous interplay of the actors, changes in their power relations, and domestic and international policy developments keep the constellations in constant flux and contribute a dynamic element. We consider Fløtten’s model to be the best option when the aim is to study how actors from below (citizens) are confronted or intertwined with the elite actors who have a potential influence on pension reform.

Data sources and methodology

A variety of sources have provided data for our study, including systematic reading of articles on pension reform in social science journals, on internet sites, and in newspapers, in both Russian and English. A variety of media outlets present articles on pension reform under a separate subject heading, so-called siuzhety, on their internet sites; articles from RIA Novosti, TASS, and Rossiiskaia gazeta for the period September 2013–December 2016 were systematically analyzed.[5] In addition, a specialized pension reform internet site that, among others, presents articles on pension reform from various media, Laboratoriia pensionnoi reformy,[6] was analyzed for the same period. Furthermore, we actively searched for relevant information on websites of those civil society organizations that were mentioned in the media or, based on our previous and exploratory research, identified as relevant stakeholders for pension reforms.

These sources were supplemented with 12 semistructured interviews conducted in the spring and summer of 2014–2015 by the Russian member of our team. From each of the influence categories we chose people who were deeply involved in pension reform and interviewed the highest-level representatives in each category that we were able to contact. We sought to map a range of opinions from civil society and government. Realizing that the number of interviews was limited, we used them to supplement more systematic reading on the reform.

Respondents were key experts on the Russian pension reform. Perspectives “from below,” our focus here, were provided by two high-level trade union representatives,[7] two high-level representatives of employers’ organizations (the largest, RSPU, and a smaller one), two academic specialists with diverging views on the pension system, and the editor of a journal specializing on pensioner issues. In addition, we interviewed officials representing two ministerial “blocs”—the “financial-economic” and the “social”—which opposed one another on pension reform (one representative from each bloc—the federal Ministry of Economic Development and the Ministry of Labor and Social Protection). Finally, representatives of the Pension Fund of Russia, the National Association of Pension Funds, and a private pension fund were interviewed (one person from each). While only six interviewees are directly cited in the text, most of them provided valuable information and different perspectives on the involvement of societal interests and contributed to different aspects of the analysis.[8]

Interviews were conducted in Russian, and citations have been translated into English by the authors. All interviewees were asked questions about the influence on pension reform of a variety of societal actors. However, the interview guides were tailored to each of the interviewees so that their responses would reflect the vast variation in their expertise. The interviews were analyzed with the use of NVivo qualitative data analysis software. A list of interviewees cited in the text can be found in the Appendix. We identify interviewees only by category in order to protect their anonymity.

Background of the reform[9]

The Soviet economy required nearly universal participation in the labor force. As a consequence, the Russian state began with an exceptionally high proportion of its population receiving pensions, higher than that in most European states.[10] The age of pension eligibility—60 for men and 55 for women—was low by international standards, and many workers as well as professionals had rights to early retirement. The system functioned on a pay-as-you-go (PAYG) basis, funded initially by a 29 percent payroll tax that employers paid to an off-budget Pension Fund. During the 1990s pension payments were often months in arrears because of the declining wage bill and large-scale tax evasion, but the State Duma (Russian federal legislative body) opposed changes in the pension system that were advocated by liberal reformers and the World Bank. President Boris Yeltsin did manage to legalize by decree nonstate pension funds in which workers could participate voluntarily, but the first serious reform was not legislated until the Putin presidency, as part of the 2002 Gref Program.

The Gref reforms, named after German Gref, the Minister of Economy and Trade of Russia in the 2000–2007 period, instituted partial privatization of the pension system by creating a mandatory invested (or funded) tier in which individual workers would accumulate savings for their own retirement. Reformers promoted the invested tier as a solution to multiple problems. They argued that private pension savings would solve the problem of the worsening “dependency ratio” between workers and pensioners in the PAYG system as Russia’s population aged.[11] Invested pensions savings would reduce Pension Fund deficits and deepen capital markets that would in turn invest in national development. The reform would also shift part of the responsibility for pensioners’ social security from the state to individual workers and subject pension savings to market risk. At the same time the Putin leadership kept off the agenda more visible reforms such as raising the retirement age.

Although promoted by Putin and his team, the pension reform was approved only after long political contestation and bargaining among opposing government ministries. The Ministry of Economic Development and the Ministry of Finance promoted the private pension tier for its potential to benefit financial markets and relieve pressures on the state budget. The Pension Fund, Ministry of Labor, and main representative of labor—the Federation of Independent Trade Unions of Russia (FNPR)—resisted because of the risk to pensioners’ financial security. Pension Fund bureaucrats also wanted to keep control over the large pool of pension savings. The two sets of governmental actors bargained over the size, regulation, and riskiness of the funded tier. A broader range of societal organizations was brought into the National Pension Council to consult on the reform, but only after most of the major decisions had been made. The process involved compromises, but in the end the Ministry of Economic Development and the Ministry of Finance won over the Pension Fund and social ministries: a mandatory funded component was added to the pension system (Cook 2007:169–173). The 2002 reform applied only to workers born after 1967 and diverted only 6 percent of pension contributions to the funded component. Although modest by international standards, the reform was a breakthrough for the privatizers in Russia.

In essence, the reform required then-current workers to finance payments for current pensioners while at the same time saving for their own future pensions, creating a “double bind” (Brooks 2008:148–191). For the six years, from 2002 to 2008, the Russian GDP grew at 7–8 percent a year, increasing the tax base and moderating pressures on the pension system. However, the Pension Fund began to run deficits in 2005 and required large subsidies from the state budget to pay current pensions. The low retirement age and the fact that one-third of Russian employees were eligible for early pensions added to the burden (Zakharov 2013). The 2008 recession intensified pressures, and after the second economic downturn in 2012 structural reforms of the pension system again appeared on the political agenda.

Controversial elements in Russian pension policy

The new round of structural reforms begun in 2013 proved challenging. The reforms would have to reach seemingly irreconcilable goals: to reduce the huge pension fund deficit and the burden of subsidies on the state budget without increasing the retirement age or reducing the living standards of current pensioners. Ministerial coalitions similar to those from the 2002 reform again debated and struggled over the terms of the reforms (Remington 2014:14–17). A package of bills was finally introduced in 2013 and adopted by the State Duma in December of that year. The reform has since undergone several amendments, and at the time of this writing is still very much a work in progress. We will not attempt to explain all the aspects of this complex reform. Instead we will focus on four of the most controversial issues that have been the subject of contestation among actors from above, inside, outside, and below. Actors both within and between each of these categories have taken conflicting positions.

The first issue generating debate and criticism of government policy is the so-called pension moratorium, which was initiated in the fall of 2013 and has continued through 2017. During the moratorium, pension assets accumulated by workers are not transferred to their individual accounts. Instead they are used for current pension payments in the PAYG system. Initially instituted for one year, the moratorium was extended in late 2015 despite assurances from the prime minister in April 2015 that it would end in that year.[12] At the time of this writing there are proposals to extend the moratorium for several additional years (Kalachikhina and Malysheva 2016). The social bloc in the government, represented by Vice Prime Minister Ol’ga Golodets, has been the most ardent supporter of the moratorium. The economic bloc, the private pension funds, and the Bank of Russia have fiercely resisted it.

The second issue concerns whether to retain the funded tier that was introduced in the 2002 reform and has been continually contested and changed since that time. Currently the employer pays 22 percent of an employee’s salary as a tax towards pensions. Sixteen percent goes into the PAYG system to cover current pensions. Still, these contributions are registered on notional individual accounts that are used to calculate future pensions of individuals according to a points system. The points earned are based on the size of the worker’s salary, length of work, and age of retirement.[13] For the remaining (and most debated) 6 percent each individual born after 1967 has a choice. The employee can transfer the money to the state Pension Fund as part of the PAYG system, whereby it is added to his or her notional account. Alternatively, it can be invested in a nonstate pension fund or in a state or nonstate management company (upravliaiushchaia kompaniia) as part of a funded (accumulative) tier. For persons born before 1967 the whole amount of 22 percent is automatically transferred to the PAYG scheme. Debates have focused on whether to keep a funded tier in the pension system at all; if the funded tier is retained whether contributions should be voluntary or mandatory; and whether those born before 1967 should be able to participate. The social bloc in the government, the Communist Party, the Just Russia (Spravedlivaia Rossiia) Party in the parliament, and the trade union movement have lobbied to eliminate the funded tier—in effect to reverse the 2002 privatization.

The current reform also introduces a rather complicated system for calculating the size of future pension payments, based on workers’ accumulation of points during their years in the labor force. This system is intended to create incentives for people to work longer before retiring, providing an alternative to a universal increase in the pension eligibility age.

The third controversial issue is whether to raise the age of pension eligibility or to penalize the payments to the large number of pensioners who continue to work. Experts and economists have long and strongly advocated for an increase in Russia’s low retirement age, but Russia’s leadership has until recently kept this proposal off the table. Initial steps in this direction were finally taken in the fall of 2015, when the government increased the retirement age for those working in state and local government administration. In December of that year Putin announced that there were no current plans to extend this increase to additional categories of workers, although he anticipated the need for such a step in the future.[14] Even if the government has planned such a move, political analysts doubt that it would be announced before the 2018 Russian presidential election.[15]

Some workers, like those who worked at so-called harmful and dangerous enterprises, have a right to early retirement, but the government is now proposing to shift the costs from the state to employers. Paying for early retirement presents a huge challenge to the Russian budget, but the government appears very reluctant to take away this right.

The fourth set of controversial issues concerns whether pensions should be indexed fully or partially to compensate for high inflation and whether such compensation should include the large number of working pensioners (Gerber and Radl 2014:160). The pension replacement rate in Russia is less than 40 percent of the average salary; pensioners who are capable often continue working to supplement their income. Although some of those involved in the pension reform debate oppose cutting compensation for working pensioners, the government has decided that, as of 2016, payments to working pensioners will no longer be indexed fully for inflation.[16]

Guarantees that pensions would be increased to compensate fully for inflation were revoked for all pensioners in 2016.[17] Past Russian legislation provided that all pensions would be indexed twice a year in line with inflation (Bazenkova 2015). However, the real value of pension payments declined by 5 percent from 2014 to 2015 (average salaries declined more sharply). Now, in a compromise between the opposing blocs, indexation is guaranteed only in so far as it can be covered by available resources.[18] It seems that pensioners will no longer be insulated from the decline in real incomes that the working population experiences. The possibility and size of pension indexation will now be determined annually by the relevant ministries.

Before the September 2016 parliamentary elections the indexation issue was much discussed. For weeks the government had been debating the possibilities for a second indexation of pensions for the current year, which had not been projected in the budget. Would the leadership increase the budget deficit to continue a popular compensation measure with the aim of maximizing pensioner turnout and support in the election, or would it delay a decision at the risk of antagonizing pensioners? Less than a month before the election Prime Minister Dmitrii Medvedev announced that, instead of a second indexation in 2016, there would be a once-only payout of 5,000 rubles to all pensioners in January 2017, money that he ordered the Ministry of Finance to find.[19] This decision seems likely to increase pressures on the state budget in the short term. However, the long-term implications of a once-only payout are more favorable for balancing future budgets than full indexation because it will establish a lower base for the next indexation than a second full indexation in 2016 would have done. At the same time such an ad hoc decision adds to the impression of a zigzagging pension reform. It seems likely to undermine confidence in Vice Prime Minister Golodets’s reassurance that 2016 is an exception and that starting in 2017 pensions would again be indexed to fully compensate for inflation (Kuznetsov 2016).

It is striking that for three of these controversial issues, elites’ decisions strongly favored interests of current and near-term pensioners over those of either current workers or the longer-term viability of Russia’s pension system. The moratorium essentially raided accumulative pension accounts to pay current retirees. Eligibility ages remained low even though both politicians and experts saw this policy as unsustainable. Full indexation of pensions every six months was maintained until 2015, and less-than-full indexation continued.[20] Pensioners did not participate in the reform, but their straightforward interests in maintaining benefits were accommodated by elites.

Influences from above, inside, and outside: A brief overview

In a related article on Russian pension reform we look into the other influences in the reform process that are identified by Fløtten—those from above, from inside, and from outside—considering how they position themselves and the alliances and tensions between them (Cook et al. forthcoming). For these three influences we give only a brief summary here. The tendency we find is that the latest reform initiatives have been elaborated and carried out within a closer circle of actors than the previous (2002) reform. The prime minister and, sometimes, the president have negotiated between the social and the financial-economic blocs in the government to reach compromises that have generally favored the social bloc. However, a seeming victory at one stage has not been a guarantee of long-term domination; both sides have seen setbacks and continued to press for change if an outcome has not been to their liking.

The main responsibility for the reform lies with the Ministry of Labor and Social Protection. A key figure in the social bloc is Vice Prime Minister Golodets, who has strongly defended existing benefits along with the Labor and Social Protection Minister Maksim Topilin. Besides the social ministries, the Pension Fund is a central player and the core of the opposition to continued privatization. The financial-economic bloc—consisting of the Ministry of Economy, with its focus on long-term macroeconomic stability, and the Ministry of Finance, with a focus on balancing the budget—are their main adversaries in the government.

The ministries have allies in various institutions that share a stake in the reform process. The trade unions and pensioners’ organizations tend to side with the social bloc, while the financial-economic bloc finds strong support from the Bank of Russia, nonstate pension funds, and employers’ organizations. However, our interviewees from some of these institutions claim that they have little direct influence on the reform process.

International organizations were actively involved in advising Russian policy makers on pension reforms in the 1990s. However, Sarah Wilson Sokhey (2015) notes that World Bank officials were largely excluded from policy deliberations for the 2002 pension reform and argues that they were much less influential than domestic actors. International organizations appear to have played no significant role in the current reform, although domestic actors have both learned from and deployed experiences of other countries in their debates.

Thus, Russian pension reform has been subject to prolonged intragovernmental struggle with two competing blocs seeking dominance and forming alliances with likeminded bureaucrats. The fact that such a struggle has been allowed to go on for years is a strong indication that the president, who normally dominates the Russian polity, has taken a largely hands-off position in order not to be blamed for unpopular decisions.

Influence from below

While it seems clear that Russian pension reform has been elite dominated, the next sections of the article look at “influence from below” on pension reform through the lenses of public opinion, activities of civil society including labor unions and pensioners’ organizations, and protests. We look at available evidence of citizens’ responses to the main controversial issues identified above: (1) the moratorium on (effectively, confiscation of) contributions to the funded tier; (2) maintenance of a mandatory funded tier in the pension system versus reversal of privatization; (3) proposals/measures to raise the age of pension eligibility; and (4) conditions for working pensioners and indexation of pensions to compensate for rising inflation.

Public Opinion

It makes sense to begin by asking whether Russian citizens are aware of changes to the pension system. Public opinion polls show that many are poorly informed about the content of the current reform. In a 2015 nationwide poll on pension reform carried out by FOM (Fond obchestvennogo mneniia) only 14 percent of respondents claimed that they understand how the pension system works, and only a minor share was able to give correct answers to rather simple factual questions on the pension system.[21]

A general lack of information, the complexity of the reform itself, and the belief that one cannot expect more than a basic minimum from the pension system (80 percent hold this belief, according to the FOM survey) are factors that help explain the low level of public interest. Indeed, the system itself is quite complex, and even our expert informants complained that it is difficult to grasp. According to a trade union representative interviewed for the project, “I cannot understand all of it, even though I am constantly involved, only a specialist [on the pension system] can do so” (Interview #2).

Pension Moratorium

Public opinion polls have shown a rather negative attitude towards the pension moratoriums, even though these same polls also reveal that a majority of people are poorly informed about them. The FOM opinion poll showed that 36 percent were against the 2015 moratorium, 15 percent in favor, while the majority was undecided or did not want to answer.[22]

According to a representative of an employers’ organization we interviewed, the introduction of a pension moratorium and its continuation for two years have had a particularly negative effect on people’s trust in the system:

One year they froze [the funded pension part], a second year they froze [it], but when they froze it a third time, it’s already a system…. Therefore, as the system was just about to stand on its own feet in people’s psyche, they started the freezing; they tore the wings off the system. (Interview #5)

Maintaining a Mandatory Funded Tier

A 2012 survey found majorities to be indifferent or opposed to keeping the funded tier. In 2014, two years into the reform, the Russian public was “largely uninformed and apathetic about the funded component of the pension system” (Sokhey 2017:230). Neither income, nor educational level, nor age affected awareness or predicted preferences. In a FOM survey conducted in spring 2015, by contrast, 62 percent of respondents opposed abolition of the funded pension tier (Krzyzak 2015). The reasons given for this view were, firstly, poorer future retirement prospects associated with demographic trends and Russian economic performance and, second, the prospects of losing the opportunity to save for retirement on an individual basis. It is noteworthy that Prime Minister Medvedev justified the government’s decision to preserve the mandatory funded tier (announced in April 2015) by referring to expert advice and public opinion.

Even if some polls show the public to be generally in favor of preserving the mandatory funded tier, their actual behavior does not testify to an active approach to their own pensions. Besides low levels of knowledge, many are confused about making difficult and uncertain choices, especially given the unpredictability caused by continuously changing rules of the game. Many ordinary people trust neither the state Pension Fund nor private actors in the pension market; indeed negative experiences with financial pyramids, devaluation of the national currency, and loss of savings have contributed to a general lack of trust in financial institutions (Belozyorov and Pisarenko 2015:166). This distrust has contributed to a large number (about 50 percent) of so-called silent (molchuny) who do not make an active independent choice about where to invest their pension money but let the state decide for them.

Raising the retirement age

The most broadly held attitudes concern the age of pension eligibility. In a nationwide representative survey carried out by VTsIOM (Russian Public Opinion Research Centre, also known as the Levada Centre) in April 2015 respondents expressed a clearly negative attitude towards increasing the retirement age. Three quarters (74 percent) opposed such a measure, while only 20 percent were in favor, with half of these only supporting an increase either for men or for women. However, there is nuance even in this broadly held view. Asked to choose between higher taxes or increasing the retirement age, a greater share (37 percent) would prefer to increase the retirement age than to raise taxes (preferred by 25 percent), with the remaining 38 percent being undecided.[23] According to a more recent VTsIOM survey, a vast majority of Russians also favor the possibility for people after retirement age to continue working while at the same time receiving a pension.[24]

Indexation and once-only payout

In a survey conducted by the Levada Centre in August 2016 the majority of the respondents (56 percent) claimed that they had heard of the newly decided once-only payout of 5,000 rubles to all pensioners in January 2017, instead of an indexation to compensate for inflation. Of those who had heard of this decision, a greater proportion expressed a negative than a positive attitude (47 and 31 percent, respectively), the rest being indifferent or finding it hard to answer (17 and 4 percent, respectively). Nonworking respondents above the retirement age held the most negative attitudes (55 percent were negative). Indeed, the notion of “anger” was mentioned by 30 percent of the retired respondents, followed by “bewilderment” (18 percent) and “resignation” (4 percent).[25]

Respondents working in the private sector expressed more consistent and critical views on pension indexation. One informant from a private pension fund saw these payments as driven by electoral pressures:

Our state is not at all motivated by what is beneficial for the economy. It took on enhanced social obligations, and all these obligations were connected with another election cycle, whether to the State Duma or presidential elections. (Interview #5)

Why is public opinion on the pension issue important if the reform is elite driven? Russian policy makers are not insulated from public pressure, and there is strong reason to believe that the Russian leadership takes public opinion into account when designing pension policy. They appear to be particularly hesitant to introduce measures that negatively affect current pensioners. It is most notable that real incomes of current recipients have been largely protected during the current reform, in part by large subsidies to the Pension Fund from the federal budget. Pensioners account for close to 40 percent of the electorate, and they are much more likely to vote in the elections than younger generations. While Putin in his early years as president sought to accommodate the needs and aspirations of a growing Russian middle class, in his third term he has been much more inclined to give priority to the older generation’s desire for stability.

Civil Society Activism

We turn now to civil society organizations participating in debates on pension reform and start with those operating in the labor market. The Federation of Independent Trade Unions of Russia (FNPR), the largest and dominant trade union organization in Russia, is one of the obligatory participants in the tripartite commissions in which pension reforms have been discussed. Their stance on pension reform has clearly been in support of the social bloc of the government. In particular they have advocated for abolishing the mandatory funded part of the pension system and reestablishing a solely publically managed distributive system.[26] In the FNPR’s view any participation in a funded tier should be voluntary. The trade union federation’s main reason for skepticism towards the mandatory funded tier is the lack of investment mechanisms that would ensure a preservation of purchasing powers of future pensioners. They are also concerned about the complexity of investing:

Unfortunately, experience shows that citizens themselves are not capable of making wise investment decisions. We cannot allow that people remain without pensions when the time for their pension payments arrives. (Interview #2)

Neither does the FNPR agree that abolishing or freezing individual pension savings is the same as stealing people’s money—they argue that all the transferred funds will be registered in individual pension accounts. Thus, according to the FNPR leader, “all transfers will work towards increasing the pensions of those insured” (Interview #2). There seems to be an alliance between FNPR and an interpartisan fraction in the Duma—the so-called interfractional working group Solidarity—that has voiced many of the same concerns as the trade unions in debates on pension reform (Pozdniakov 2015).

Although FNPR and other trade unions have expressed concern and taken positions on pension reform, their direct influence appears to be rather limited. Moreover, the trade unions’ standing among the general population remains weak, and more independent trade unions have low potential for mass mobilization (Crowley 2002; Vinogradova et al. 2015; Davis 2016). Smaller independent unions have taken positions but have no presence at the federal level and even less influence on the direction of reforms.[27]

On the employers’ side, the Russian Union of Industrialists and Entrepreneurs (RSPP) has been particularly active in promoting its stance on pension reform. In 2006 it established a working group on the development of the pension system, with three main proposals: (1) a flexible retirement age; (2) to allow people born before 1967 back into the funded pillar; and (3) to introduce tax incentives for voluntary pension savings (Krzyzak 2015). More recently the RSPP has advocated increasing the retirement age and has been a strong proponent of keeping and strengthening the funded component of the pension system.[28] Thus, while trade unions have been supporters of the approach of the social bloc in the government, the employers’ side has tended to support the financial-economic bloc (Remington 2014:11–12). There are also issues on which trade unions and employers have joined forces, such as the possibility for working pensioners to continue receiving pensions.[29]

According to several of our interviewees, RSPP was a rather influential actor in the previous (2002) round of pension reforms but has been less involved in the current, ongoing reform. Our RSPP interviewee informed that although the organization is involved in various consultative arenas for dialogue with the government on pension reform, “often we do not succeed in changing the government’s position” and that “we do not agree with everything.” As an example of an issue where RSPP has had some influence, the interviewee mentioned the issue of working pensioners where RSPP put pressure on the government to “fully reestablish the rights of the working pensioners.” A compromise was reached whereby working pensioners are still able to accumulate pension eligibility, though at a lower rate than those below retirement age. The RSPP representative claimed this as a partial victory for their organization. The interviewee furthermore believed that joining forces with experts, individual employers as well as trade unions on the issue had been crucial for convincing the government (Interview #6).

Together with representatives of the state, the Russian trade unions and employers’ organizations have a tripartite commission for regulation of social and work relations at the federal level, with 30 representatives from each side.[30] The commission regularly discusses issues related to pension reform. It is important to note that besides tripartite negotiations on salaries and labor conditions, this commission is first and foremost a consultative body whose aim is to advise government institutions responsible for policy development and legislation on work-related issues and to seek joint solutions and compromises in cases where they have different views or interests. There are indeed examples where the state has taken an issue off the meeting agenda because the sides stand far apart. One incident concerned exactly an announced further discussion of pension payments to working pensioners to be raised at a meeting in October 2015, which was removed from the meeting agenda by the state.[31] When asked about the importance of such bodies for policy making in the pension sphere, our interviewees gave a mixed rating, indicating that the important decisions are made elsewhere:

There are various channels: councils under the Ministry of Labor [and Social Protection], the tripartite commission. We have many different bodies, and one can hear about them everywhere. But you have to understand that the issue of pension security has left the level of social-labor relations to become a political issue (Interview #4).

Probably the most influential organization with the aim of defending the rights of pensioners in Russia is the Union of Pensioners (RUP), one of the largest civil society organizations in the country with approximately 1.4 million members. The RUP is far from an opposition movement; in 2011 it was one of the first organizations to join the government-organized All-Russian People’s Front, and it emphasizes joining forces with the state and local government as well as religious and other civic organizations to promote pensioners’ rights and interests. The RUP is represented in many of the consultative bodies set up to give advice on pension issues. RUP seems to balance its position on the most controversial pension reform issues and informs its membership about the different opinions and implications of different approaches rather than representing a critical voice in the debates.[32] The RUP leader Valerii Riazanskii has, however, spoken in favor of removing the funded component of the system, leaving it to individuals, or their employers, to pay additional contributions towards their pensions on a purely voluntary basis outside the system. He also supports the pension moratorium.[33] Riazanskii would prefer indexation over one-time payouts to compensate for inflation, but accepted that the economy did not allow for a full compensation in 2016.[34] On most issues RUP therefore seems to stand closer to the social than the financial-economic bloc in the government.

Veterans’ organizations are first and foremost concerned with the pension rights of veterans and work on issues such as retiring before the official retirement age, keeping pensions while remaining in work, keeping pension privileges for certain categories, and so on. Veterans were among the most affected during monetization of social benefits in the early 2000s (Cook 2007; Kulmala and Tarasenko 2016). However, these organizations seem not to have played an active role in pension reform processes, although they enjoy respect in Russian society and are seen by many as deserving special attention and thus appear to have a considerable indirect impact.

In sum, trade unions, employers’, pensioners’, and veterans’ organizations have voiced positions on pension reform, but all seem to be at best minor players that support positions of key governmental actors—organized employers support the financial-economic bloc while unions, pensioners’, and veterans’ organizations line up with the social bloc. Interviews and other evidence indicate that these organizations exercise little independent influence.

The most active and outspoken pressure from “below”—as defined in our model—comes from the academic community. A number of think tanks, research institutions, and independent experts have been vocal in pressing their positions on pension reform. Most are prominent economists or pension system experts concerned with fiscal integrity and long-term viability of Russia’s pension system. They advocate raising the retirement age and maintaining the funded tier and warn against overspending on social welfare today at the expense of future generations. Their positions generally line up with those of the financial-economic bloc, with which they have close ties. The most prominent and most often cited such expert is former Finance Minister Aleksei Kudrin, who is the head of the Civil Initiatives Committee (Komitet grazhdanskikh initsiativ).[35] Another prominent pension reform expert is Oksana Siniavskаia from the Centre for Studies of Income and Living Standards at the Higher School of Economics, who has worked as consultant for the Russian government on pension reform issues.[36]

There are also academic institutions and think tanks active in the pension-reform debate that have a more left-leaning approach. Institut globalizatsii i sotsial’nykh dvizhenii, headed by Boris Kagarlitskii, has, for example, made extensive analysis of Russian pension reform (see, e.g., Kagarlitskii et al. 2013). Interestingly, the institute favors preserving the funded part of the pension system but with more public control over investment of contributions. As regards the question of retirement age, the institute favors a flexible approach, but to keep trust in the system the institute’s representatives stress that under no circumstances should already-acquired rights be cut. Although Kagarlitskii has been invited to many public debates on pension reform, it is doubtful that he and his team have any substantial impact on policy making in the sphere.

Table 1 lists the main civil society actors and their stances on the four most controversial pension policy issues and comparison with the standpoints of the social and financial blocs in the government as well as actual implemented policy.

| Accumulative pensions (Social bloc skeptical; financial-economic bloc mostly in favor) |

Pension moratorium (Social bloc in favor; financial-economic bloc against) |

Increase of retirement age (Social bloc against; financial-economic bloc in favor) |

Indexation of pensions (Social bloc in favor; financial-economic bloc mixed) |

|

| Union of pensioners | Skeptical | Supports | Against | In favor, but accepts rationale for exceptions |

| Veterans’ organizations | Skeptical | Not vocal | Against | In favor |

| FNPR (federation of trade unions) | Skeptical | In favor | Against | In favor |

| RSPP (main employers’ organization) |

In favor, should be strengthened | Against | In favor of flexibility | Against |

| Academic institutions / think tanks / experts | Mostly in favor | Against | Mostly in favor | Mostly against |

| Public opinion | Mixed | Against | Against | Negative to once-only payout; attitudes towards indexation not found |

| Government policy | From obligatory to voluntary. Continuously debated | Introduced 2013. Continues, although prime minister promised abolishment | Talk about necessity of rise, but only a few measures taken so far (state officials) | Dynamic, was in legislation, abolished 2016, but pensioners compensated by cash payment in 2017 |

Societal Protests

Recent polls show that only a small and shrinking proportion of Russians (11 percent in October 2015) is ready to participate in public protests and demonstrations, and less than one in five considers that such protests are likely to take place.[37] Nevertheless, the past few years have seen a rise of local protests over social issues in Russia. In the first six months of 2015 protest increased by 15 percent compared with the same period of 2014, and with a high emphasis on social issues, according to a study by the Committee on Civil Initiatives.[38] As noted earlier, recent protests against housing reforms and evictions, hospital closings and consolidations, inadequate facilities for children with disabilities, and other issues have been recorded, although these protests have remained local and particularistic (Greene 2014; Holm-Hansen 2016).

Against this background, one could say that Russian citizens have been conspicuously silent in their response to the Russian pension reform. As pointed out by one of our interviewees, when asked about public expressions of resistance towards the reform: “None at all. There have not been any” (Interview #1). In fact we have found some scattered incidents of protest relating to pension reform, but most date back to 2012–2013 and are locally oriented, far from covering the whole country.[39] No organized social movement or united civil society platform is attempting to influence policy making in the sphere.

Our interviewees suggest several factors they see as contributing to lack of protest in Russia. One respondent noted that many people think of pensions as an obligation of the state, something for which the state is responsible, not something that they created, their own deferred earnings (Interview #1). Secondly, interviewees stressed that the reform is difficult to understand, especially the recently introduced points system, that workers cannot anticipate or calculate the effects on their pensions and will understand the implications only much later, when they go to apply for their pensions. In general, as mentioned above, levels of literacy on pension security are quite low. One respondent pointed out that the people are not experiencing effects of the reform in the present and that this situation was diametrically opposite to the 2005 reforms that sparked large protests (Interview #3). Finally, interviewees pointed to path dependency from communist rule to explain why Russians do not protest: “Yes, this is our culture, this is the effect of 70 years … of the socialist system. That is, people have been to such an extent oppressed and intimidated, that they are not ready [to protest]” (Interview #2).

Why so little engagement from below?

Given the strong social mobilization and disruptive protests against the monetization of benefits in 2005, mainly by pensioners, and protests against pension reforms in, for example, Latin America, why has there been so little societal response to the recent reforms that affect pensioners’ rights? Most of the activity affecting the reforms, as we have shown, has taken place among actors from above and inside—the presidential administration, ministries, and the Pension Fund. In civil society it is mainly economists and pension experts who have tried to influence the reforms. The mass of civil society has not mobilized on the pension issue in organized or spontaneous demonstrations, actions of protests, strikes, petitions, meetings, or other ways of showing discontent, as it has, to at least some extent, in other areas of social policy.

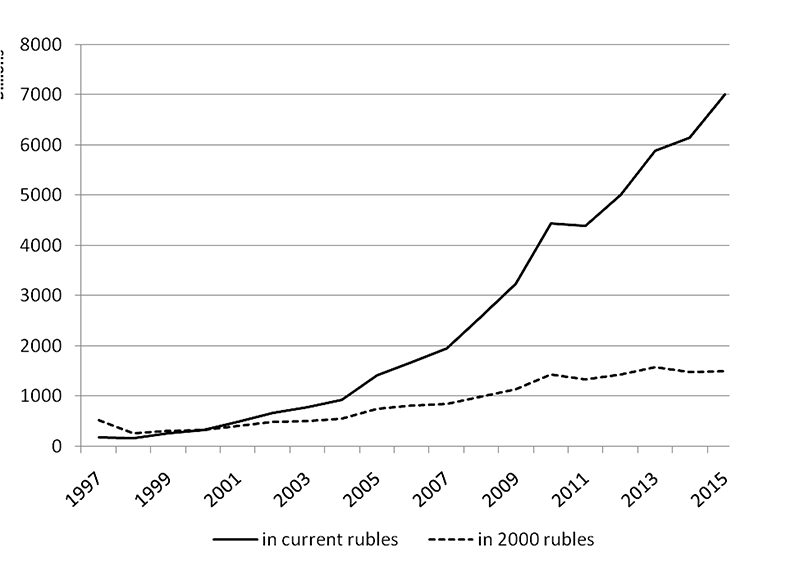

The main reason for the lack of societal response is that elites have managed pension reform to protect the benefits of current pensioners. As Figure 2 shows, the real value of payments received by current pensioners has been largely protected against inflation by steady increases in nominal pension payments. Near-term retirees have been protected by decisions not to raise the pension eligibility age. A voluntary accumulative tier will provide more funds for payouts to pensioners.[40] By contrast, workers paying into the pension system have suffered losses of contributions to their individual funded accounts. However, those losses are not tangible because the money would not have been paid out until far into the future, when the generations born after 1967 retire. Further, public opinion research (cited above) shows that many workers never understood how funded accounts were supposed to work and have little knowledge about or interest in the reforms. Low public engagement also results from the complex nature of pension reform. The general weakness of Russia’s civil society (discussed above) also contributed to the lack of response.

This policy approach contrasts sharply with that of the 2005 benefits reform, when significant and tangible benefits were taken away all at once from a massive group of mainly older beneficiaries. Although the earlier reform promised to “monetize” benefits—convert them to cash payments—both the immediate experience of the state “clawing back” benefits in a period of prosperity and pensioners’ distrust of the promised cash substitutes fueled outrage and led to large protests.

Dominance of the social bloc in reform policy accounts for these propensioner policy outcomes. As Table 1 (above) shows, the policies supported by the social bloc, and so far largely adopted, line up closely with the preferences expressed by the Union of Pensioners, veterans’ organizations, and major trade unions (FNPR)—the organizations closest to pensioners. While our research indicates that these organizations did not exercise direct pressure or influence, they articulate the interests of pensioners. The financial-economic bloc, by contrast, favored policies that would have avoided the moratorium, raised the age of pension eligibility, and cut or ended indexation of pensions. Explaining in full why the social bloc has dominated is beyond the scope of this article. However, we observe that debates in the government over pension policy referred frequently to pensioners’ interests, and the public speeches of Putin, Medvedev, Golodets, and other leaders regularly assured pensioners that their rights would not be taken away.

Conclusion

In this article we have used Fløtten’s actor- and interaction-oriented model of reform from above, inside, below, and outside to assess Russian post-2013 pension reform. In particular, we have examined influence from below, with emphasis on public opinion, civil society organizations, and protest. We show that the reforms have been elite driven and that social and financial-economic blocs within the government have struggled over policies to reduce the pension burden. Alliances of actors have been formed that crosscut the four types of influences in Fløtten’s model, but we find that influence from “above” and “inside” have been much stronger than those from “outside” and “below.”

Neither bloc has tried to involve the public in development of pension policy. Although some civil society organizations have engaged in the pension issue, their direct influence has been very limited. Protests on the issue are virtually absent.

The weakness of Russia’s civil society matters. The lack of societal involvement left the policy field almost entirely to elites, who have fought over pension reforms since 2013, creating great policy instability. Every year there were conflicting promises and late decisions about the moratorium, the accumulative tier, policy shifts, and unresolved issues. More importantly, decisions were left to blocs of elites with conflicting interests: giving preference to the rights of current pensioners against those of current workers and the longer term viability of the pension system. There were no societal actors to press for negotiation and compromises that would take account of both workers’ and pensioners’ interests, as well as the broad societal interest in fiscal solvency. Russian elites are not accountable to society for the results of their decisions. Pensioners’ rights are protected because the social bloc wins, not because their organizations have influence.

Still, public opinion and the potential for social instability appear to have had considerable impact on the government’s pension policy. Putin’s government has until now maintained what R. Kent Weaver (1986) termed “blame avoidance” for pension reforms. The social protests that erupted in 2005 in connection with the monetization of social benefits demonstrated to the regime the strong mobilization capacities of pensioners. The more recent localized protests have raised the specter of new mobilizations against loss of social benefits. The Russian government has seemed reluctant to introduce more radical steps—which would impose immediate losses nationwide—to solve the pension fund deficit crisis, for fear of risking social stability.

Finally, it should be mentioned that while mass mobilization against pension reform has taken place in a number of countries, recently most notably in Latin America, there are many countries with much stronger civil societies than Russia’s where few people protest over pension reforms. This common public passivity is well explained by Paul Pierson’s (1994) classic argument that welfare retrenchment provokes strong pushback when it imposes immediate costs on large groups of current beneficiaries but can fly by “under the radar” when costs are deferred into the future or otherwise obscured, so not visible to any organized or conscious group in the present. As Pierson shows, deferral of pension cuts and other costs of welfare state retrenchment is a common strategy of political elites. The breadth and immediacy of benefit cutbacks are likely the main reason why Russian pensioners took to the streets in 2005, and protection of current beneficiaries a reason they refrained from protesting during the current reform.

The strategy of protecting pensioners has begun to hit its limits in the face of Russia’s prolonged economic downturn and weak recovery. As noted above, the practice of full pension indexation was abandoned in 2016, and the real value of pensions has been falling. In a recent public opinion survey, low pensions were named as one of the most important problems facing families in Russia.[42] The deeper structural reforms advocated by economists and pension specialists have been delayed but not necessarily abandoned. It remains to be seen what the future will bring and how Russian pensioners and workers will respond.

References

- Aasland, Aadne, Mikkel Berg-Nordlie, and Elena Bogdanova. 2016. “Encouraged but Controlled: Governance Networks in Russian Regions.” East European Politics 32(2):148–169.

- Bazenkova, Anastasia. 2015. “Balancing Russia’s Budget Could Cost Pensioners $46 Billion.” Moscow Times, June 24. Retrieved November 3, 2017 (https://themoscowtimes.com/articles/balancing-russias-budget-could-cost-pensioners-46-billion-47669).

- Belozyorov, Sergey, and Zhanna Pisarenko. 2015. “Pension Reforms in Countries with Developed and Transitional Economies.” Ekonomika regiona 1(4):158–169.

- Brooks, Sarah. 2008. Social Protection and the Market in Latin America: The Transformation of Social Security Institutions. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Cook, Linda J. 2007. Postcommunist Welfare States: Reform Politics in Russia and Eastern Europe. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Cook, Linda J., Aadne Aasland, and Daria Prisyazhnyuk. Forthcoming. “The Russian Pension System under Quadruple Influence.” Problems of Post-Communism.

- Crowley, Stephen. 2002. “Comprehending the Weakness of Russia’s Unions.” Demokratizatsiya 10(2):230–255.

- Davis, Sue. [2006] 2016. “Russian Trade Unions.” Pp. 197–210 in Russian Civil Society: A Critical Assessment, edited by Alfred B. Evans, Jr., Laura A. Henry, and Lisa McIntosh Sundstrom. London: Routledge.

- Ebbinghaus, Bernhard. 2011. “The Role of Trade Unions in European Pension Reforms: From ‘Old’ to ‘New’ Politics?” European Journal of Industrial Relations 17(4):315–331.

- Evans, Alfred B., Jr., Laura A. Henry, and Lisa McIntosh Sundstrom. [2006] 2016. Russian Civil Society: A Critical Assessment. London: Routledge.

- Flikke, Geir. 2016. “Resurgent Authoritarianism: The Case of Russia’s New NGO Legislation.” Post-Soviet Affairs 32(2):103–131.

- Fløtten, Tone. 2006. “Quadruple Pressure—A Framework for the Study of Welfare-State Development.” Paper presented at the conference “Social Policy in the Baltic States,” May 8–10, Riga, Latvia.

- Gerber, Theodore P., and Jonas Radl. 2014. “Pushed, Pulled, or Blocked? The Elderly and the Labor Market in Post-Soviet Russia.” Social Science Research 45:152–169.

- Greene, Samuel. 2014. Moscow in Movement: Power and Opposition in Putin’s Russia. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Holm-Hansen, Jørn. 2016. “Organized Protest against Housing and Utility Reform in Russia: How Does It Work and What Is Its Impact?” Paper presented at the conference “Between the Carrot and the Stick,” January 28–29, Aleksanteri Institute, University of Helsinki, Finland.

- Kagarlitskii, Boris I., V. G. Koltashov, A. V. Ochkina, and D. I. Grigor’ev. 2013. Pensionnaia sistema v Rossii: Tupiki biurokraticheskikh reform i perspektivy preobrazovaniia. Moscow: Institute for Globalization and Social Movements.

- Kalachikhina, Iuliia, and Elena Malysheva. 2016. “Pensii ne ottaiali.” Gazeta.ru, August 31. Retrieved November 3, 2017 (https://www.gazeta.ru/business/2016/08/31/10168895.shtml).

- Krzyzak, Krystyna. 2015. “Russian Pension Funds Set for More Secure Future.” Investment & Pensions Europe, April 23. Retrieved November 3, 2017 (https://www.ipe.com/countries/cee/russian-pension-funds-set-for-more-secure-future/10007650.article).

- Kulmala, Meri, Markus Kainu, Jouko Nikula, and Markku Kivinen. 2014. “Paradoxes of Agency: Democracy and Welfare in Russia.” Demokratizatsiya 22(4):523–552.

- Kulmala, Meri, and Anna Tarasenko. 2016. “Interest Representation and Social Policy Making: Russian Veterans’ Organisations as Brokers between the State and Society.” Europe-Asia Studies 68(1):138–163.

- Kuznetsov, Aleksei. 2016. “Kak indeksiruiutsia pensii v Rossii.” Komsomol’skaia pravda, August 31. Retrieved November 3, 2017 (http://www.kompravda.eu/daily/26575/3591123/).

- Ljubownikow, Sergej, Jo Crotty, and Peter W. Rodgers. 2013. “The State and Civil Society in Post-Soviet Russia: The Development of a Russian-Style Civil Society.” Progress in Development Studies 13(2):153–166.

- Pierson, Paul. 1994. Dismantling the Welfare State. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Pozdniakov, Aleksei. 2015. “Profsoiuzy raskritikovali pensionnuiu reformu.” Trud, April 28. Retrieved November 3, 2017 (http://www.trud.ru/article/28-04-2015/1324605_profsojuzy_raskritikovali_pensionnuju_reformu.html).

- Remington, Thomas F. 2014. “The Politics of Social Insurance in Russia and China.” Paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Political Science Association, August 28–31, Washington, DC.

- Robertson, Graeme B. 2010. The Politics of Protest in Hybrid Regimes: Managing Dissent in Post-Communist Russia. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Sokhey, Sarah Wilson. 2015. “Market-Oriented Reforms as a Tool of State-Building: Russian Pension Reform in 2001.” Europe-Asia Studies 67(5):695–717.

- Sokhey, Sarah Wilson. 2017. The Political Economy of Pension Policy Reversal in Post-Communist Countries. London: Cambridge University Press.

- Vinogradova, Elena, Irina Kozina, and Linda J. Cook. 2015. “Labor Relations in Russia: Moving to a ‘Market Social Contract’?,” Problems of Post-Communism 62(4):193–203.

- Weaver, R. Kent. 1986. “The Politics of Blame Avoidance.” Journal of Public Policy 6(4):371–398.

- Zakharov, Mikhail. 2013. Sotsial’noe strakhovanie v Rossii: Proshloe, nastoiashchee i perspektivy razvitiia. Trudovye pensii, posobiia, vyplaty postradavshim na proizvodstve. Moscow: Izdatel’stvo “Prospekt.”

Appendix

| # | Respondent’s affiliation | Gender | Date and place of interview |

| 1 | Federal ministry (financial-economic bloc) | female | May 15, 2015, Moscow |

| 2 | Federation of trade unions | male | June 3, 2015, Moscow |

| 3 | Association of private pension funds | male | June 16, 2015, Moscow |

| 4 | Trade union for state employees | male | June 26, 2015, Moscow |

| 5 | Employers’ organization | male | July 13, 2015, Moscow |

| 6 | Russian Union of Industrialists and Entrepreneurs | female | July 22, 2015, Moscow |

Российская пенсионная реформа: почему вовлеченность «снизу» слаба?

Одне Осланд – старший исследователь, PhD, Университетский колледж Осло и Акерсхус по прикладным наукам (Норвегия). Адрес для переписки: NIBR, Oslo and Akershus University College of Applied Sciences, PO Box 4, St. Olavs Plass, 0130 Oslo, Norway. aadne.aasland@nibr.hioa.no.

Линда Дж. Кук – профессор политологии и славянских исследований Университета Брауна (США). Адрес для переписки: Department of Political Science, Brown University, Box 1844, 36 Prospect Street, Providence, RI 02912, USA. linda_cook@brown.edu.

Дарья Присяжнюк – кандидат социологических наук, старший преподаватель департамента социологии факультета социальных наук Национального исследовательского университета «Высшая школа экономики». Адрес для переписки: НИУ ВШЭ, Мясницкая 20, Москва, 101000, Россия. dprisyazhnyuk@hse.ru.

В статье анализируются разного уровня влияния, оказанные на российскую пенсионную реформу 2012 года, с акцентом на влияния «снизу». Мы выявляем четыре основных спорных вопроса, связанных с пенсионной реформой: изменения в системе индивидуальных пенсионных счетов, финансирование системы, пенсионный возраст и индексация пенсий. В статье используется аналитическая схема реформ всеобщего благосостояния, разработанная Тонем Флеттеном, которую мы используем для определения четырех направлений, оказывающих влияние на российскую пенсионную реформу: «сверху» (высокопоставленные лица, принимающие решения), «изнутри» (государственная бюрократия и профессионалы), «извне» (политика международных организаций) и «снизу» (гражданское общество и общественное мнение). Мы утверждаем, что реформа была запущена «сверху» и «изнутри» элитами, которые в значительной степени защищают интересы нынешних пенсионеров и граждан предпенсионного возраста, в то время как бремя расходов несут в основном работающие ныне и будущие пенсионеры. В центре статьи – анализ влияния на пенсионную систему «снизу»: здесь представлено описание и анализ общественного мнения в отношении пенсионной реформы, описаны позиции и возможности влияния на изменения в сфере со стороны объединений пенсионеров и других общественных организаций, а также продемонстрировано почти полное отсутствие протестов. Мы утверждаем, что поддержание текущих пенсий, отсрочка расходов на отдаленное будущее, а также сложный и часто неясный характер реформ объясняют отсутствие несогласий и сопротивлений «снизу», в то время как российское гражданское общество остается слабым, граждане протестуют против потери социальных прав. Данная статья объясняет слабость общественного участия или протеста в ответ на эту крупную социальную реформу. Исследование основано на анализе газетных публикаций, веб-страниц организаций гражданского общества, а также академических и политических документов на русском и английском языках. Анализ документов был дополнен двенадцатью полуструктурированными интервью с различными экспертами в области пенсионной реформы.

Ключевые слова: пенсионная реформа; Российская Федерация; гражданское общество; общественное мнение; протесты

- The laws on insurance, on cumulative pensions, and on guaranteed rights when forming or investing pension savings can be found, respectively, at: http://www.consultant.ru/document/cons_doc_LAW_156525, http://www.consultant.ru/document/cons_doc_LAW_156541, and http://www.45-90.ru/images/content/New_Formula/FZ_422_garpn.pdf. ↩

- The article is part of an international project on Russian welfare reform funded by the Research Council of Norway’s NORRUSS programme (Project no. 220615) and carried out in 2014–2016. ↩

- See, for example, BBC reports on huge protests in Brazil (http://www.bbc.com/news/world-latin-america-39287415) and Chile (http://www.bbc.com/news/world-latin-america-39401766). ↩

- With the minor exceptions of civil servants, whose pension eligibility age has been increased, as we discuss below. ↩

- They can be found at: https://ria.ru/trend/Russia_pension_reform_05102012 (RIA Novosti); http://tass.ru/pensionnaya-reforma (TASS); and https://rg.ru/sujet/72/ (Rossiiskaia gazeta). ↩

- http://pensionreform.ru/pension_news. ↩

- Leaders of the Interregional Trade Union for State and Municipal Employees and the Union of Russian Trade Unions. ↩

- For perspectives from “outside” we decided to rely on policy documents of the World Bank, IMF, and OECD, but all informants were asked about external influence on the reforms. ↩

- Much of the text in this section draws on Cook (2007). ↩

- Pension payments in Russia were, however, much lower, both in real terms and as a percentage of wage replacement. ↩

- Demographic experts predict that by 2035 the population of Russian pensioners will have increased by 10 million while the working population will increase by an estimated 11 million (Kulmala et al. 2014:532). Even if these projections overstate future demands on the pension system, an increasingly smaller share of the population will have to work to provide pensions to an increasingly larger share of old-age pensioners. ↩

- “Golodets: Moratorii na nakopitel’nuiu chast’ pensii stal eshche aktual’nee,” Ria Novosti, August 24, 2015 (https://ria.ru/society/20150824/1204207653.html). ↩

- Workers continue to pay for today’s pensioners but their contributions are also credited to notional accounts, which get a rate of return broadly linked to earnings growth. When they retire, their pension benefits are based on the notional capital they have accumulated. ↩

- “Putin rasskazal ob obiazatel’nom povyshenii pensionnogo vozrasta,” TVTs, December 17, 2015 (http://www.tvc.ru/news/show/id/83010). ↩

- “Pensiia 2016 v Rossii: Povyshenie pensionnogo vozrasta, kogda proizoidet, chto budet v 2016 godu,” Poliksal, June 6, 2016 (http://poliksal.ru/novosti-v-mire/41135-pensiya-2016-v-rossii-povyshenie-pensionnogo-vozrasta-kogda-proizoydet-chto-budet-v-2016-godu.html). ↩

- “Budet li otmena pensii rabotaiushchim pensioneram v 2016 godu?,” 2016-god.com, October 10, 2015 (http://2016-god.com/budet-li-otmena-pensii-rabotayushhim-pensioneram-v-2016-godu/). ↩

- “Pensii v Rossii za god uvelichilis’ na 853 rublia,” Lenta.ru, August 23, 2016 (http://lenta.ru/news/2015/04/22/pens850/). ↩

- “Putin podpisal zakon ob otmene indeksatsii pensii dlia rabotaiushchikh pensionerov,” TASS, December 29, 2015 (http://tass.ru/obschestvo/2564347). ↩

- “Minfin otsenil ekonomiiu ot zameny indeksatsii pensii razovoi vyplatoi,” RBK, September 9, 2016 (http://www.rbc.ru/economics/09/09/2016/57d2b2d09a794727d6612c9d). ↩

- The longer-term maintenance of the funded tier was not an issue of immediate importance. ↩

- “Opros: Rossiiane ne nadeiutsia, chto pensiia smozhet obespechit’ im starost’,” Ria Novosti, September 30, 2015 (http://ria.ru/society/20150930/1293894203.html). ↩

- A later poll about prolonging the moratorium also for 2016 gives corresponding negative results, see “VTsIOM: Reshenie o zamorazhivanii pensionnykh nakoplenii v 2016 godu podderzhivaiut 12% naseleniia,” Vedomosti, November 18, 2015 (https://www.vedomosti.ru/politics/news/2015/11/18/617383-vtsiom-zamorozke-pensionnih-nakoplenii). ↩

- “Glas naroda protiv liubykh pensionnykh reform,” Ekonomika segodnia, April 9, 2015 (http://rueconomics.ru/50913-glas-naroda-protiv-lyubyih-pensionnyih-reform/). ↩

- “Bolee treti rossiian planiruiut rabotat’ na pensii – opros,” Vedomosti, November 11, 2015 (https://www.vedomosti.ru/politics/news/2015/11/19/617524-bolee-treti-rossiyan-planiruyut-rabotat-na-pensii-opros). ↩

- “Zamena indeksatsii pensii razovoi vyplatoi,” Levada-Tsentr, September 21, 2016 (http://www.levada.ru/2016/09/21/zamena-indeksatsii-razovoj-vyplatoj/). ↩

- See, e.g., “Profsoiuzy raskritikovali pensionnuiu reformu,” Trud, April 28, 2015 (http://www.trud.ru/article/28-04-2015/1324605_profsojuzy_raskritikovali_pensionnuju_reformu.html). ↩

- See, e.g., “Pochemu russkie – ne frantsuzy?,” Institut “Kollektivnoe deistvie,” July 19, 2011 (http://www.ikd.ru/node/14939). ↩

- “RSPP podderzhivaet initsiativu Minfina o povyshenii pensionnogo vozrasta,” TASS, October 14, 2015 (http://tass.ru/obschestvo/2347025). ↩

- “Pensii v povestke dnia RTK,” Profsoiuzy segodnia, October 12, 2015 (http://www.unionstoday.ru/news/russian/2015/10/12/21065). ↩

- For more on the commission, see the Russian government webpage (http://government.ru/department/141/about). ↩

- “Pensii v povestke dnia RTK,” Profsoiuzy segodnia, October 12, 2015 (http://www.unionstoday.ru/news/russian/2015/10/12/21065). ↩

- See, e.g., “Vybrat’ pensiiu za poltora mesiatsa,” Soiuz pensionerov Rossii, November 17, 2015 (http://www.rospensioner.ru/node/3146), summarizing the pros and cons of extending the deadline to opt for staying with the insurance pension (PAYG) or for the funded pension type. ↩

- “Soiuz pensionerov: ‘Zamorozka’ nakopitel’noi chasti udarit po fondam, a ne po liudiam,” NSN, September 2, 2016 (http://nsn.fm/economy/soyuz-pensionerov-nakopitelnuyu-chast-pensii-otmenyat.php). ↩

- “‘Soiuz pensionerov Rossii’: Razovye vyplaty khuzhe indeksatsii,” NSN, August 17, 2016 (http://nsn.fm/society/soyuz-pensionerov-rossii-razovye-vyplaty-khuzhe-indeksatsii-pensiy.php). ↩

- For a short summary of his views on pension reform, see “Aleksei Kudrin i pensionnaia reforma,” Kadrovik Plus (http://kadrovik-plus.ru/about/news/detail.php?ID=1879). ↩

- See her profession profile at the Higher School of Economics’ website (http://www.hse.ru/en/org/persons/11328583#experience). ↩

- “Interfax: Poll: Russians Continue to Lose Interest in Protests,” Johnson’s Russia List, November 9, 2015 (http://russialist.org/interfax-poll-russians-continue-to-lose-interest-in-protests/). ↩

- Website of Komitet grazhdanskikh initsiativ (https://komitetgi.ru/analytics/2563/). ↩

- See Institut “Kollektivnoe deistvie” website (http://www.ikd.ru/taxonomy/term/41?page=1). ↩

- Working pensioners have been hurt by the decision to stop fully indexing their payments. ↩

- Calculations by Natalia Forrat. Sources: Sotsial’noe polozheniie i uroven’ zhizni naseleniia Rossii 2003. Statisticheskii sbornik, p. 194, Table 6.19; Sotsial’noe polozheniie i uroven’ zhizni naseleniia Rossii 2005. Statisticheskii sbornik, p. 196, Table 6.3; “Konsolidirovannyi biudzhet Rossiiskoi Federatsii i biudzhetov gosudarstvennykh vnebiudzhetnykh fondov” (http://roskazna.ru/ispolnenie-byudzhetov/konsolidirovannyj-byudzhet/); “Indeksy potrebitel’skikh tsen na tovary i uslugi po Rossiiskoi Federatsii v 1991–2015 gg.,” Federal’naia sluzhba gosudarstvennoi statistiki (http://www.gks.ru/free_doc/new_site/prices/potr/2015/I-ipc.xlsx). ↩

- “Public Opinion in Russia: Russians’ Attitudes on Economic and Domestic Issues,” Associated Press–NORC Center for Public Affairs Research (http://www.apnorc.org/projects/Pages/HTML%20Reports/public-opinion-in-russia-russians-attitudes-on-the-economic-and-domestic-issues-issue-brief.aspx). ↩