The Soul of Stone: Mineral Symbolism in Vepsian Villages of Karelia

Anna Varfolomeeva is a PhD candidate in the Department of Environmental Sciences and Policy, Central European University. Address for correspondence: Department of Environmental Sciences and Policy, Central European University, Nador u. 9, 1051 Budapest, Hungary. varfolomeeva_anna@phd.ceu.edu.

This article is based on field research conducted with support from Central European University (Research Support Scheme). I would like to thank my supervisor Tamara Steger for her support, as well as the two anonymous reviewers and the editors of Laboratorium for their helpful comments and suggestions.

This article is a case study of the northern Vepses, an indigenous group residing in the Republic of Karelia, and their relations with mining industry. As early as the eighteenth century, Vepses in Karelia were involved in the extraction of rare decorative minerals (gabbro-diabase and raspberry quartzite), and this involvement continues today. The article discusses the variety of symbolic meanings stone has for contemporary residents of Vepsian villages, who see it simultaneously as a source of hardship, struggle, and pride. Local residents view nature and stoneworking as interconnected, seeing mining development in the region as a consequence of its natural richness. This case study illustrates that indigenous lifestyles, industrial development, and nature may be perceived as coexisting and interconnected elements.

Keywords: Indigenous Peoples; Vepses; Karelia; Mining; Stone Symbolism

”I will tell you a story,” the car driver said, smiling, after he found out I was going to see the local quarry. ”Many years ago, when Napoleon was in Russia, he saw our quartzite and liked it so much that he immediately ordered it for his future tombstone. That’s how famous our stone is.” It felt strange to talk about Napoleon on the road between Shoksha and Kvartsitny, two of the villages in Karelia where indigenous Vepses reside. However, local residents are used to it, as the rare crimson-colored stone connects their villages with Vladimir Lenin’s Mausoleum in Moscow, the palaces of Saint Petersburg, and even Napoleon’s sarcophagus in Paris.

This article discusses the influence of dominant discourses and local experiences on contemporary perceptions of the mining industry in Vepsian villages in the Republic of Karelia (northwest of Russia). In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, Vepses residing in Karelia were involved in the extraction of rare decorative minerals, and this involvement continues today. The identity of Karelian Vepses, as well as people from other parts of the country who moved to their villages to work in the quarries, was in many ways formed under the impact of mining.

Stuart Hall (1990:225) defines identities as “the names we give to the different ways we are positioned by, and position ourselves within, the narratives of the past.” Drawing on Hall’s theory, Tanya Murray Li (2000:151) argues that indigenous self-identification is neither natural nor simply constructed; it is rather a “positioning which draws upon historically sedimented practices, landscapes or repertoires of meaning.” The articulation of indigenous identity in many cases reflects the general relations of power in society. Within these dominant discourses relations between indigenous communities and extractive industries are often presented through oppositions such as “traditional activities” versus “mining development” or “indigenous person” versus “industrial worker.” However, as a number of studies show, these dichotomies can be reductive. Indigenous groups may have been involved in resource extraction in the past (Pringle 1997; Cameron 2011; Cooper 2011), industrial workers in the North may develop attachments to their natural surrounds (Bolotova 2012), and reindeer herders may work in the oil industry (Dudeck 2008).

Existing indigenous-settler power relations are nowadays questioned by aboriginal communities, and the emergence of indigenous subjects is a process taking place in many different parts of the world. However, in trying to establish their subjectivities, indigenous communities may accept the discourses of the state or extractive businesses. In Russia, due to its strong legacy of state superiority as well as the weakness of contemporary legislation, cases of indigenous resistance against extractive businesses are few. Many indigenous residents choose silent resistance over open conflicts: from changing mobility patterns and everyday practices (Dudeck 2012) to suicide as an act of ultimate protest (Stammler 2011). Brian Donahoe (2013) points out that indigenous groups in Russia in most cases accept the external definitions and categories used to construct their social identities.

However, the emergence of indigenous subjects cannot be viewed as simply ”constructed” or ”imposed” by states or extractive businesses. This process is driven by, among other factors, indigenous historical experiences and the specificities of their landscape. One such strong factor influencing the shape of local identities among northern Vepses, a small indigenous group in Karelia, is their historical engagement with stoneworking. Nowadays quartzite and diabase form an important part of everyday life in the villages, dominating the landscape, conversations, and activities. In the following sections of this article I will analyze the material and symbolic meanings of gabbro-diabase and raspberry quartzite in Vepsian communities under the influence of dominant state discourses and local interactions with the mining industry. The Soviet-era discourse of struggling with stone or mastering it still has an impact on contemporary perceptions of mining in Vepsian villages, although nowadays the roles are often reversed, and informants figure the diabase and quartzite as a force shaping their lives. At the same time, many residents of Vepsian villages are proud of their local stone due to its rarity, toughness, and glorious history, and this attachment forms a substantial part of their local identity. This research shows that the relationship between indigenous communities and extractive industries may go beyond established dichotomies and historical connections to minerals in some cases become an important factor influencing residents’ attitudes to industrial development in the region.

Methodology

This research incorporates several ethnographic methods including participant observation and in-depth interviews conducted with the residents of three Vepsian villages—Shoksha, Kvartsitny, and Rybreka—in 2015–2016 (22 recorded interviews, as well as informal communication with local residents). The age of the respondents varied between 47 and 88 years; thus, most of them were employed in mining industry during both Soviet and post-Soviet years (it was a common practice in the villages to continue working at the quarry even after retirement, just shifting to legkii trud—light work). Twenty-one out of 22 respondents either had worked at diabase or quartzite quarries in the past or were employed there at the time of the interview; one informant worked at the music school in Kvartsitny. The extensive work experience of most of my informants provided valuable data on the changes to the mining industry in the villages since the postwar years. The interviews were semistructured and lasted between 40 minutes and 2.5 hours; in most cases they began with introductory questions on the informant’s family history and background, then moved to several thematic areas including their perceptions of work in the quarry during Soviet and post-Soviet periods, relations (if any) with Vepsian language and culture, the informant’s views on present-day life in the village and currently operating mining companies, and their ways of spending free time in the past and present. Snowball sampling was used in order to enlarge the set of possible informants.

Shoksha and Kvartsitny are situated close to the two quarries where quartzite used to be extracted; one of the mining sites which used to produce quartzite gravel stones is now closed, while another is privately owned and producing quartzite blocks on a small scale. The settlements have experienced different models of development: whereas Shoksha is an old Vepsian village, Kvartsitny was built in the 1970s near the newly opened quarry. In Rybreka, also a centuries-old Vepsian village, several private companies are currently extracting gabbro-diabase.

The initial aim of my fieldwork was to conduct interviews with different groups of locals: indigenous and nonindigenous residents, mining workers, and indigenous activists. However, this division is not strict, as the same person may easily play multiple roles in the community, for example being both an indigenous citizen and an activist or a local resident and a company representative. Besides, soon after starting fieldwork I learned how vague and fluid the notion of “indigeneity” is when applied to the diverse communities of Vepsian villages in Karelia. Several of my respondents did not consider themselves Vepses, identifying as Russian despite being from the region or speaking the Vepsian language in their childhood. At the same time, there were people who moved to the region because of work or family reasons and after several years felt local. I was told a story about a German woman moving to Karelia with her Vepsian husband after World War I; she quickly learned the Vepsian language and started working in the quarries (Interview #18). One of my informants, Valentina, originally from Ukraine, also learned the Vepsian language, became very keen on Karelian nature, and defined herself as a “Ukrainized Veps” (Interview #16).

This article, therefore, does not aim to draw a line between the relations with stone experienced by different ethnic groups residing in the villages. While between the seventeenth and nineteenth centuries these settlements were populated mostly by Vepses, later, especially during the Soviet period, a lot of people moved to the villages from other places in Karelia or from other regions. Although they were not Vepsian by ethnicity, the features of landscape, traditional occupations of local residents, and the centuries-long connection to decorative stones in the area impacted their personalities, especially as most of them started working in the quarries and therefore mining became an important part of their lives. While at the beginning of each interview I asked whether the informant’s family was from the villages, I did not aim to interview only those people whose families had been in the district for generations, as the identities of those who moved to the villages from other regions were also shaped by local attitudes to mining as well as by the specificities of Karelian nature.

In order to identify state discourses on nature and resource extraction and their influence on local attitudes towards mining in Prionezhskii district, fieldwork also included an analysis of relevant publications in the Karelian press. This article primarily concentrates on the publications in Kommunist Prionezh’ia (Communist of Prionezhskii district), a leading local newspaper (renamed Prionezh’e in 1991), also using materials from Krasnoe Sheltozero (Red Sheltozero) a newspaper which was published in one of the villages of Prionezhskii district. The Soviet-era publications cited in this article cover the period between the 1930s and 1970s. Newspapers were the primary medium for disseminating Soviet ideology alongside radio and, later, cinema (Zassoursky 2004:6). As Minna-Mari Salminen points out, the Soviet media system was closed to Western influences and had several main goals, the first of which was to spread information about the Soviet way of life and its supremacy (2009:28). Thus, my analysis of Soviet-era newspapers serves as a reflection of state ideology and the main messages it tried to send to its audience. However, in order to show the media discourses of today, I also include data from materials published in 1991–2015 in several regional newspapers: Prionezh’e, Kareliia, and Kodima (a newspaper which is published partly in Vepsian). The analysis of the Soviet and post-Soviet newspapers alongside contemporary interview data will show how the dominant discourses on natural resource extraction correlate with people’s perceptions of mining in the region.

The next section of the article is devoted to the discourses about indigenous communities in relation to extractive industry development and to the symbolic meaning stone has for those involved in resource extraction. Both the dominant state discourses and historical connections with mining and landscape influence the residents of Vepsian villages in Karelia and their perceptions of mining in the region.

Discourses on indigeneity and extractive industries

European representations of indigenous peoples have their origins in the Enlightenment, when the first conceptualizations of “exotic others”appeared. Aboriginal societies were then perceived as the embodiment of Western dreams about freedom and simplicity or, on the other hand, as savages who needed to be “civilized” (Nakashima and Roué 2002:316). In today’s world, many of these assumptions are still preserved and are reflected in perceptions of indigeneity in relation to resource extraction. Whether viewed through the lens of “environmental nobility” or colonial discourses, indigenous communities are often presented as societies living in the past, refusing changes and denying the positive or negative effects of industrial development.

While the concept of ecological nobility aims to empower indigenous peoples, in many cases it reinforces existing discrimination (Ellingson 2001) by embedding their complex relations with nature and industry into a concrete paradigm. The notion of “ecological nobility” creates a burden for indigenous communities, as in many cases they are expected to live up to the unreachable standards imposed on them (Nadasdy 2005:293). Failure to maintain these standards leads to new labels like “nonauthentic,” “ignoble,” or “antienvironmentalist.” At the same time, the colonial approach to indigeneity is still strong. Native communities occupying lands which possess untapped resources are still sometimes described as primitive (Gedicks 2001:17).

The established discourses on indigenous peoples influence the debates related to mining development in different parts of the world. Stuart Kirsch presents the case study of the indigenous movement related to Ok Tedi mine in Papua New Guinea, concluding that one of the reasons for the campaign’s eventual failure was its inability to overcome representations that reduced indigenous views to a single dimension. The campaign, like many other indigenous movements, had more complex objectives than simply closing down the mine. The movement asked for compensation for environmental damages and less pollution of the river, but at the same time the participants hoped that the mine would continue operating as it brought economic benefits to the community. However, their claims did not have the expected effect as they stepped out of an “antidevelopment” paradigm (Kirsch 2007:314). As Kirsch notes, “instead of allegories about environmental activism, anthropologists need ethnographic accounts that better represent the complex and potentially contradictory ambitions of indigenous movements” (314). Ximena Warnaars and Andrew Bebbington’s study (2014:109) focusing on the impacts of natural resource extraction on indigenous and rural livelihoods in Ecuador shows that state models of extractive industry development are often not informed by the needs of affected populations. The authors argue that conflicts around mining are the result of divergent perceptions of development and differing approaches to land use, territorial control, and the environment (110).

In the case of Russia, as Florian Stammler (2011:262) notes, many indigenous communities internalize the idea of the superiority of state interests, which is a part of the Soviet legacy. The indigenous elite, mostly trained in the Soviet Union, often views confrontation with the state as morally questionable and values collective interests over individual needs. Besides, the Soviet ideology promoted a common development model of “one unified people,” and thus the coexistence of industry with herding or fishing was envisaged (Stammler and Forbes 2006:52). As a result, indigenous groups affected do not have the tradition, the power, and the connectedness allowing them to resist industrial development (Stammler 2011:262). Fieldwork among reindeer-herding nomads showed that there is no significant resistance against extractive industry development but rather an expressed will to coexist (252), as the Soviet idea of the “collective,” as Stammler notes, serves as important social glue (249). Another example illustrating this coexistence is Stephan Dudeck’s (2008) case study of indigenous oil workers in Kogalym, a town in Khanty-Mansi Autonomous Okrug, where a lot of Khanty and Nenets reindeer herders are employed by oil companies. Surprisingly, indigenous oil workers do not express significant concerns related to their contested relationships with the environment, and they counterbalance the negative impacts of industrial development with the new opportunities such work offers.

As Stammler’s and Dudeck’s studies show, indigenous cultures and mining development are not necessarily in opposition, and there is a possibility for coexistence. This case study of Vepses illustrates the possible links and connections between indigenous lifestyles, stoneworking, and nature through the symbolic value added to stone.

Materiality and animism of stone

Christopher Tilley (2004:19) views animism as a system of thought wherein “inanimate” natural objects such as trees, stones, and mountains, or buildings, monuments, and artifacts, are treated as being alive or having a soul and akin to a person. In this system people, animals, and things reciprocally participate in one another’s existence (20). Tim Ingold (2006:10) holds a similar notion of animism, describing it as a constant process whereby people and things “continuously and reciprocally bring one another into existence.” It is not a one-directional infusion of spirit into a nonliving substance; rather it goes beyond the whole discrepancy between the categories of living and nonliving things. This process is only a part of a continuous intertwining among people and objects in the world, where everything in the environment is linked and entangled (13).

It may seem that indigenous lifestyles and mining are naturally opposed; however, there is a number of studies showing the importance of mineral extraction for aboriginal societies. Heather Pringle (1997) describes how widely dispersed and important metal was in prehistoric Arctic cultures. Pringle points out that archaeological findings in the Canadian Arctic and Greenland discovered metal objects hundreds of kilometers from known sources of iron and copper, implying the existence of an established metal trade. Metals were so important for Arctic Inuit communities that they recycled broken pieces over and over again; besides, the possession of metals apparently reflected a person’s social ranking (Pringle 1997:766).

Emilie Cameron criticizes the established view on mining as something alien to indigenous cultures and traces the significant role of “copper stories” in different Canadian Inuit narrative. These narratives illustrate that metal had been appreciated by indigenous communities long before their contact with Europeans (Cameron 2011:178). Kory Cooper relates the perception of metals in ancient cultures with Tim Ingold’s concept of animism—as metals were appreciated by indigenous cultures of North America not only for their visual appeal and practical purposes but also for their association with supernatural spirits (Cooper 2011:254). These studies help to rethink the established indigenous narratives away from postcolonial framing and the traditional binary notions such as “traditional” versus “modern,” “Inuit” versus “European,” and so on (Cameron 2011:188). Contrary to presenting copper mining as a wholly modern technology alienating indigenous peoples from their traditional way of life, the studies of Cameron and Cooper offer ground for more complex analyses of indigenous encounters with extractive industries.

Due to their beauty, rarity, and durability, precious stones are often given symbolic meaning in different cultures. An interesting example of diamond symbolism in Sakha Republic (a region in Siberia) is presented by Tatiana Argounova-Low; she discusses the concept of symbolic ownership over diamonds. After diamonds were discovered in Sakha, they were initially represented in the culture as a pan-Soviet thing, but consequently the representation became more “ethnicized” and associated with Sakha local identity (Argounova-Low 2004:263). Veronica Davidov refers to the complex symbolism of gold in the Soviet Union: it was “both a symbol and an anxiety-provoking reality that holds within itself the danger of pollution and must be handled with extreme caution” (2013b:24).

Traces of stone cults are visible across the whole territory of the Russian tundra, from the Kola Peninsula to Kamchatka (Titov 1976:4). The Sami seids (sacred boulders) and stone labyrinths at the Kola Peninsula are well-known examples. Some of the seids look like huge rocks standing on smaller stones; several small rocks are also sometimes placed on the surface of a seid (Titov 1976:18). Many researchers relate seids to various cults: they could have been used as prayer altars before hunting or as protection against evil spirits. Seids could also be interpreted as the places where the spirits of the dead gathered or as patrons giving happiness to those who make their sacrifices near them. Labyrinths created out of medium-sized rocks are another example of stone cult constructions that were most probably used for sacrifices (Fefilat’ev 2007:2). Seids and stone labyrinths are also present in the territory of Karelia (Mel’nikov 1998). Karelia is also known for its petroglyphs—rock carvings off the eastern coast of Lake Onega and the White Sea (Stoliar 2001) representing images of hunting, skiing, and religious rituals. As the next part of the article will illustrate, stones were also an important part of Vepsian beliefs and rites.

The symbolic and material role stone played—or still plays—in the life of indigenous groups is an important factor that helps us to understand their views on extractive industry development in the region. However, this dimension is almost absent from academic discourse on extractive industries and indigenous communities. Aboriginal peoples’ relations with stoneworking in many cases reflects global discourses on resource governance and indigeneity; at the same time, they may be presupposed by people’s daily practices and local experiences, as well as their historical relations with the landscape and with precious stones.

The history of mining in Prionezhskii district

The Republic of Karelia is a well-known tourist destination due to the beauty of its natural environment. Karelia is also rich in mineral resources including iron, chrome, uranium, granite, diabase, marble, shungite, and precious metals. The mining industry alongside forestry is one of the primary economic activities in the region; Karelia, as one of the local newspapers states, ”stands on stone legs” (Kareliia, July 13, 2006, p. 8). There are concerns, however, that Karelia is overreliant on resource exploitation: between 2009 and 2015, the share of resource extraction in the Karelian economy grew by 24 percent, whereas the share of processing industries dropped by 16 percent (Hille 2015).

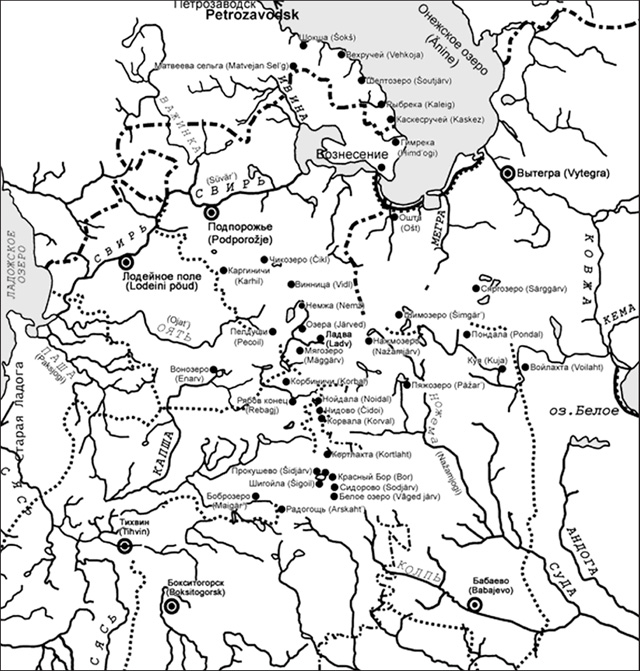

The region is home to several Finno-Ugric minorities: Karelians, Vepses, and Finns. According to the 2010 census, there are 3,423 Vepses in Karelia (5,936 total in Russia, as Vepses also reside in nearby Leningrad and Vologda regions). Historically Vepses inhabited the areas around Lake Onega, Lake Ladoga, and White Lake (Vinokurova 1994:5); however, due to administrative divisions and insufficient transport connections Vepsian villages belonging to different regions became more isolated from each other (Strogal’shchikova 2014:12). The Vepses residing in Karelia are known as “northern Vepses” and are separated geographically from the Vepses residing in other regions (12). The region inhabited by Vepses in Karelia is called Prionezhskii district or Prionezh’e.

The specificities of landscape often influence economic activities in a particular territory (Potakhin 2008). Thus, as the region on the shore of Lake Onega was rich in two rare minerals—raspberry quartzite (also referred to as “crimson quartzite”) and gabbro-diabase—Vepses became involved in stonecutting crafts. Diabase, a dark-grey rock that becomes black when polished, is found in large quantities only in Karelia (near Rybreka), Ukraine, and Australia (Davidov 2013a). As for raspberry quartzite, it is especially valuable due to its unusual dark-red color, durability, and rarity: the quarry near Shoksha in Karelia is the only place in the world where it is extracted.

As early as the eighteenth century Vepses were famous in other Russian regions as skilled stoneworkers (Strogal’shchikova 2012:140). In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries both minerals were used for decorative purposes in several cities, including Moscow (Cathedral of Christ the Saviour) and Saint Petersburg (the altar of Saint Isaac’s Cathedral, the stone-block pavement of the Kazan’ Cathedral, decorations of the Winter Palace). In 1847, 27 blocks of raspberry quartzite were sent to France for the construction of Napoleon’s sarcophagus (Strogal’shchikova 2014). Vepsian stoneworking brigades regularly accompanied the minerals to construction sites. Many skilled villagers worked as otkhodniki (seasonal labor migrants) at construction sites in different cities. The Vepsian ethnographic museum in Sheltozero (opened in 1967) is situated in the former house of Ivan Mel’kin who managed the transfer of Vepsian stone to the construction sites of Saint Petersburg and Petrozavodsk in the nineteenth century. The museum contains a special exhibition devoted to mining and the travels of Vepsian work brigades.

In the Soviet period, mining in the Vepsian area was actively developed. The first state mine of gabbro-diabase was opened in 1924; the stone was mostly transferred to Leningrad over water. At first all the works were performed manually, but within 10 years the mine was to a large extent mechanized. Both minerals were used for decorative purposes in Petrozavodsk, Moscow, Leningrad, Yalta, and many other cities. One of the most famous examples is the Red Square ensemble: its stone-block pavement is made of gabbro-diabase, and raspberry quartzite was used for the construction of Vladimir Lenin’s Mausoleum. In the Soviet period both diabase and quartzite quarries were managed by the state, but Vepses continued to be symbolically linked to the stone. In the poem “The Ballad on Vepsian Stone” (1970) Taisto Summanen, a Karelian poet, recalls the history of Vepsian mining with a poetic image of the small people commemorating Lenin in stone (for the Mausoleum): “We will create our song not out of words, but out of stone—for centuries.”

After the fall of the Soviet Union, the quartzite and gabbro-diabase mines were partly closed and partly sold to private companies, the majority of these being from other Russian regions, but some of them foreign or involving foreign partners (Davidov 2013a:139). Due to financial difficulties, most of the enterprises, after turning into joint-stock companies, were closed in the 1990s (Prionezh’e, May 6, 1997, p. 1). Raspberry quartzite extraction has almost stopped: today the only remaining private mining site is making gravestones, and, as locals say, only around 20 people are employed there (Interview #20). Gabbro-diabase mining is still actively carried out by private companies (Strogal’shchikova 2012:141). Most of the extracted stone is taken out of Karelia (Interview #20). The majority of men residing in Shoksha and Kvartsitny continue to be involved in the mining industry, but now they mostly work for the neighboring village of Rybreka, where private mining of gabbro-diabase is actively developing, or at the quarries in other Karelian regions. The largest mining company in Rybreka is Karelkamen’ which positions itself as the successor to the former state enterprise (Prionezh’e, September 12, 2014, p. 1). The taxes paid by Karelkamen’ constitute more than 80 percent of the Prionezhskii district’s budget; thus, Rybreka and other villages largely depend on it, and they are largely supported by local administration (Trofimova 2015). This specific position of Karelkamen’ is reflected in regional newspaper publications where Karelkamen’ is often referred to as the village’s ”pivotal enterprise” and in general pictured very positively (Prionezh’e, July 25, 2014, p. 1; September 12, 2014, p. 1). Other mining companies, however, are sometimes blamed for damaging the forest around the villages (Prionezh’e, May 23, 2014, p. 1), problems with waste treatment facilities (Kareliia, January 24, 1995, p. 2), or for occupying public roads around the settlements (Prionezh’e, April 9, 2015, p. 4). Local residents are upset that the wealth of Karelian mineral resources often does not improve their life conditions. Though the mining companies of Prionezhskii district are selling rare stones all around the world, they are unable to repair the road in Rybreka (Kareliia, July 13, 2006, p. 8); though the raspberry quartzite has earned a world fame, many families in Kvartsitny live in poverty (Prionezh’e, May 27, 2005, p. 4). These publications demonstrate that the Vepsian villages in Karelia largely depend on resource extraction, and it is important to understand not only the material benefits of mining but also its symbolic meanings. The next part of the article will discuss the symbolism of the natural world in Vepsian communities as well as the importance of stone in today’s life of Prionezhskii district.

Vepsian stone and its symbolism

Madis Arukask (2014:324) refers to the relations of Vepses with the natural world as “animistic communication with nature.” Different spaces, including fields, forest, lakes, and rivers, were animated and had their “masters” (in Vepsian, ižand). Belief in the mecanižand (forest master) reflects the dual attitude of Vepses to the forest: on the one hand, it is perceived as the source of well-being; on the other hand, as a place full of dangers (Vinokurova 1994). While Vepsian villages are usually surrounded by forest and thus a lot of beliefs are related to it (Salve 1995), the Vepses in Karelia are also closely connected to lakes and rivers, especially Lake Onega, as most of the villages are situated on its shore. The master of water is the source of similar ambivalence: while providing people with fish and being responsible for the change of seasons, he could also cause harm for fishermen or even kidnap children (Vinokurova 2006).

Stones were also given sacred meanings in Vepsian culture: Arukask (2014:327) gives the example of Ristkivi (cross-stone), which can be found in the deep forest near Nemzha, a Vepsian village in the Leningrad region. Only locals know the way to the sacred stone; they use it as a place for prayers and appeals to God and, probably, also to the masters of nature (as at the end of each visit the villagers leave some food near the stone “for forest spirit” [327]). Similar sacred stones can be found near other Vepsian villages in the Leningrad region. The warming of lake water in June was believed among northern Vepses to be the result of D’umal (the god of thunder and lightning) placing a warm stone in the water (Vinokurova 2010:70). Gravel stones (čuurkivi) were a part of several important rituals related to weddings or funerals (Vinokurova 2010, 2012). The name of one of the former villages in Prionezhskii district—Čuurušk—comes from this stone (Strogal’shchikova 2015).

In Shoksha, Kvartsitny, and Rybreka today it is easy to notice what the main occupation of local residents is. The stone is everywhere; it is incorporated into pavements and house designs or simply lies around—by the houses, near the road, or even in the forest. Local residents are accustomed to the sound of trucks carrying gabbro-diabase to Petrozavodsk, the capital of Karelia, though the people living close to the main road often complain about the noise and dust caused by the trucks (Interviews #9, #15). This symbolic domination of the landscape reflects the general importance of stoneworking in the life of villagers. Many local residents are employed in the stoneworking industry, so this topic dominates their conversations. The life of many families is divided into 15-day periods when the husband and father is either na vakhte—at his working shift—or at home, when a lot of household tasks are managed (Interviews #13, #20). The instruments of local miners form a part of local school exhibitions in Rybreka. Kindergarten children learn poems and songs about stone to perform at various events (Interview #11), including Miner’s Day, which is celebrated in the end of August in Rybreka and attracts many people from neighboring villages (Kodima, September 2013, p. 4). High school students prepare presentations about local mining dynasties for the annual school conference, and many of them plan to work with stone in the future.

The next part of the article discusses several important symbolic meanings stone has for contemporary residents of Vepsian villages and how these meanings are informed by dominant state discourses reflected in Soviet-era newspapers as well as local interactions with nature and mining. For my informants the material importance of stone as a source of prosperity for the villages and its symbolic meaning as a part of their identity are often interconnected. They speak about stoneworking as an unhealthy but profitable occupation, about the rarity and uniqueness of diabase and raspberry quartzite, and about the well-arranged life they had in the past in comparison to the unstable present.

Cursed stone

In 1932, Karelian journalist Sergei Norin published a collection of feature articles; one of them, “Vzorvannye gory” (Blown mountains), is devoted to industrial development in the Vepsian area in Karelia. The story presents a sharp contrast between mining in the early twentieth century and Soviet-era stone extraction. It starts with a vivid description of the dark and cold mountain area populated by wolves and bears. In the early twentieth century, Norin writes, stone extraction was a hard occupation, as all the work had to be done manually and the workers had no stable income. The workers called the extracted stone pieces ”prokliatyi kivi” (cursed stone, where the first word is Russian and the second Vepsian) as they suffered so much because of it (Norin 1949:8).

The theme of ”cursed stone” is present in other publications devoted to the pre-Soviet period of stoneworking. For example, a compilation of materials on handicraft industries in Karelia published in 1895 describes stoneworking as an extremely harmful occupation. A lot of Vepsian stoneworkers at that time died at the age of 50–55 from tuberculosis (Blagoveshchenskii and Gariazin 1895:30). Whereas in the Soviet period local newspapers often mentioned that working with stone is hard, these hardships are presented more like a challenge. For example, the article published in 1972 describes a working day of stonecutters: ”This occupation requires a lot of strength, agility, and courage. Try to drop a huge piece of stone after explosion, when it is literally at the very edge of the cliff” (Kommunist Prionezh’ia,[1] July 15, 1972, p. 2). The article concentrates on the results and achievements rather than the toil of stoneworking.

Sometimes the hardships related to mining are simply omitted in publications. A newspaper article from 1934 states that 220 women were employed at the mining site. In order to free working women from looking after children, a nursery was opened in 1930 (Krasnoe Sheltozero, November 7, 1934, p. 4). The tone of the article is positive, and there is no implication that working in the mine could be difficult for women. However, this theme was present in several of the interviews I conducted. Several former workers of quartzite and diabase quarries mentioned that there was no special treatment for pregnant women—they had to work the same amount of hours with the same working standards, and the work often involved lifting stones or other heavy objects (Interviews #2, #10, #16). In general, during the Soviet period women were often employed by the quarries as unskilled labor which in many cases meant extremely heavy work. One of the informants from Shoksha, Liudmila, says, ”I had a good job, I was cleaning—not like those poor women who had to work with the stone outside, in any weather” (Interview #5). Evgeniia, who started working at the wharf in Rybreka after the war loading stones to the ships with other women, describes:

In autumn we were shipping stones until October. I remember how the last barge came in October, just before the November holidays. There were such waves, and we had to load the stones. And the waves were all over the wharf. So we were all wet, from head to feet…. My boots were full of water, and the water is cold in autumn, you know. After that loading I fell ill and had fever, I was even taken to hospital. (Interview #16)

The motives of stone as a source of suffering or health disorders are often present in the interviews. Almost every informant mentioned that stoneworking industry is harmful for health as rock dust causes silicosis, a pulmonary illness (Interviews #2, #8, #14, #17, #18). Galina, aged 78, stressed that a lot of the people working in the quartzite quarry with her in the 1960s had died from silicosis (Interview #2). Other possible health problems were also mentioned, through less frequently. One of the former workers I interviewed in Shoksha said, ”This quartzite, it has radiation! When they blow up the stone you can see it glowing—that’s a sign it’s radiated” (Interview #4). Many informants talked about the hardships of stone production: workers had to spend hours outside, even when it was –29C in winter (at –30C they had the right to stop working). Most of the tasks of stone chopping and grinding were performed by women. Another challenge was that some jobs in the quarries required working shifts lasting from 8 a.m. to 4 p.m., from 4 p.m. to 12 a.m., and then the night shift—from midnight to 8 a.m. (Interview #16). The shifts (and therefore daily routines) changed every week. Those who had children mostly needed to ask grandparents or other relatives for help.

When talking about the difficulties related to mining work, the informants in most cases talked about them as something ordinary. A lot of informants presented working in the quarries as inevitable and stressed that they had no choice: “Where else could I go? There was no other production in the village, just the promkombinat [consumer goods manufacturing], the sovkhoz [state farm], and our mine” (Interview #22); “There was no other job for me, except for stone loading” (Interview #16); “What else could the people do?” (Interview #15); “Work is work, you know” (Interview #10). Sometimes the hardships were even presented as a joke: three times during fieldwork I was told the same anecdote about tourists from Leningrad visiting one of the quarries and asking the women working with stone, ”For how many years have you been sentenced?” taking them for prisoners. ”But no, we were doing it voluntarily!” a local woman told me, laughing. While the villagers knew that the stoneworking jobs might be harmful and challenging, a lot of them still chose this occupation as salaries were much higher than in the neighboring collective farm in Sheltozero and other employment options (Interview #2). Besides, as workers in a hazardous industry they had the right to retire five years earlier than other Soviet citizens, and their retirement benefits were higher.

While most of the informants talked about the hard labor of the past as a fact, they were still nostalgic as, at that time, ”there was stability” (Interview #19) and ”people didn’t have to search for jobs in other places, everybody was working” (Interview #4). This contrast between a secure past and an unstable present was especially visible in interviews with the residents of Shoksha and Kvartsitny, as they indeed experienced a noticeable change: in the 1990s the settlements lost their main source of employment (the quarry producing gravel stones). Though many informants focused on the hardships of mining in the past, a number of them also stressed that they felt motivated and hopeful about the future then (Interviews #19, #14). As one of the older women told me, “Our life was hard, but it was a good and merry life” (Interview #16).

The depiction of mining as a hazardous industry is therefore common in newspaper publications of the Soviet period as well as interviews with post-Soviet residents of Vepsian villages. However, while Soviet-era newspapers present stoneworkers as heroes overcoming hardships triumphantly, my informants describe these hardships in all their vividness, stressing that they chose the occupation because of its economic benefits and a lack of other jobs. Most informants do not perceive the hardship of mining as possible to overcome, but rather as a force influencing and shaping their lives.

Struggling with stone and nature

The end of the feature by Sergei Norin shows the capitulation of wild nature to the power of human progress: the formerly empty mountain is now populated, the wolves have left the area, and the bear was shot, as it was preventing road construction (Norin 1949:36). The theme of struggle and symbolic ”victory” over stone is often present in Soviet-period local newspapers and other publications, and it goes in line with the general discourse of romanticized industrialization (Bolotova and Vorobyev 2007:30) and the theme of humankind’s victory over wild nature. Active mining development in the Soviet time went alongside significant transformations of the landscape. This transformation became especially significant in the 1970s, when the new modern settlement of Kvartsitny was built close to the mining deposit, resulting in significant migration from other Russian regions to Karelia.

One of the articles published in 1972 in a local newspaper is titled ”Struggling with Stone” and describes the work and responsibilities of excavator driver Mikhail Kalinin. The article states: ”He [Kalinin] has devoted 10 years to his favorite machine, his homeland, and the battle with stone. And as evidences show, he always won this battle” (KP, June 15, 1972, p. 2). Another article devoted to the development of a new mine describes the area where the stone will soon be extracted: ”All the trees have been cut, and here and there huge stones and stubs are hulked up.... It may seem that there has recently been a fierce battle in this area” (KP, June 8, 1972, p. 1). The descriptions of ”struggles” and ”battles” in Soviet newspapers showed the evidence of human progress and conquering nature for a better future. One of the articles in the local newspaper is titled ”Ukrotitel’ kamnia” (The stone tamer), with ”tamer” indicating the victory of man over a wild creature and, consequently, man’s victory over nature itself (KP, May 27, 1967, pp. 1, 3).

In order to win over the stone it was considered important to understand it, to feel its “soul.” One of the articles published in Kommunist Prionezh’ia states, ”Because of workers’ great enthusiasm, the stone opened its soul and yielded” (KP, November 14, 1967, p. 2). Another article mentions, ”You should combat stone wisely; its power is widely known. You just need to find its weak spot and use it” (KP, July 15, 1972, p. 2). Both of these articles present stone as an animate object: it has its own soul and character, and stoneworking is pictured as a competition where it is extremely important to know one’s rival. Ivan Kostin (1977:53), the author of a series of sketches devoted to mining in Karelia, describes a scene where he asked a stoneworking foreman: “What do you think is the most important part of your work?”The foreman replied: “It is hard to say, but probably the most important part is to feel the ’character’ of stone, to know all its peculiarities.”

In many cases publications relate people’s character to stone or to nature in general. There are articles that reflect on the severe northern environment forming especially strong characters (KP, January 22, 1972, p. 2). In his feature article Norin reflects on the changes in the Vepsian district over the first years of professional mining development: ”Struggling with the storm of difficulties, with the waves of obstacles, people were working on the shore. They were tougher than diabase” (1949:34). In Kostin’s sketches an older stoneworker tells his younger colleague: ”Stone respects those who are patient” (1977:10). Sometimes such comparisons between people and stone were also drawn in interviews, as respondents stressed that working with stone required physical and moral strength: “It was hard work…. One had to be firm” (Interview #16).

During the interviews done in 2015 ”battles” with nature were perceived as negative and harmful. One of the respondents said, ”In Soviet times they drained the swamp…. They thought it would be better, but the swamp was there for a reason, it was needed…. Now we have fewer berries, and there are forest fires every summer” (Interview #3). Several other respondents mentioned that there were fewer berries in the surrounding forests and fewer fish in the lake, but they were not sure about the possible reasons for this decline and more often blamed the tourism companies from Moscow for buying the land near the lake and polluting the water. ”Are you from Petrozavodsk?” one resident of Kvartsitny asked me, adding: ”Good, I was already thinking it’s somebody from Moscow again” (Interview #12). He later explained that tourists from Moscow were expropriating the land near the villages, including the territory of the former monastery and the shore of Lake Onega. A shop assistant in Kvartsitny called the villagers ”cobblers without shoes” as they no longer had access to the lakeshore because of the tourism boom—”the whole shore had been bought.” Private mining enterprises are also often blamed for damaging the ecology, as the informants complain about the dust and noise created by mining (Interviews #9, #15). At the same time, even when private companies are accused of mismanagement, the importance of mining itself was never in doubt for informants.

Most of the people I talked to were deeply connected to their surrounding nature: they often went to the forest and to the lake, grew vegetables and flowers. A woman who moved to Kvartsitny from Shoksha described how she would help her mother with the garden and the cows in the mornings, then go to work, and come back to help with the household in the evening (Interview #7). Most informants had similar experiences combining working in the quarries and growing vegetables, fishing, hunting, and picking mushrooms and berries (Interview #6). They do not perceive the coexistence of the mining industry and natural riches as necessarily a problem and do not see a need for future “struggles” with nature.

Being proud of stone

Another theme that is present in both Soviet-era publications and my fieldwork data is a sense of pride in the ”Vepsian stone.” This theme is related to feelings of locality and belonging. People’s interactions with landscape serve as a primary source for the establishment of human belonging, rootedness, and familiarity (Tilley 1994:26); the feeling of belonging may be cultivated through local myths, oral histories, narratives, or museums. The unique stone that was extracted in the Vepsian villages made their residents feel that they were engaged into important and valuable activity. Besides, as the stone was used for many well-known monuments around the country, the stoneworkers’ hard labor ultimately connected them symbolically to the whole country.

This feeling of belonging was strong at the beginning of the twentieth century when Vepsian stoneworkers were saying proudly, ”Our oldsters were building [Saint] Petersburg” (Kuznetsov 1905:106). But during the Soviet period their pride in the unique and valuable stone was especially cultivated. In the office of the main mining company of Prionezhskii region there was a map showing all the destinations where Vepsian stone was going (Kostin 1977:14). The workers were aware of the destination of each new order, and they felt they were doing an important job.

In 1967 raspberry quartzite from Shoksha was used for the construction of the Unknown Soldier’s Grave in Moscow. Four representatives from Shoksha and Rybreka were invited to the monument’s opening ceremony, and local newspapers in Prionezhskii region widely covered their trip. Grigorii Medvedev, one of the participants of the stoneworking delegation, was in Moscow for the first time. The delegation spent a week in the capital; they were present at the opening ceremony, attended the reception at the Palace of Congresses, and went to the theater. The article ends with the proclamation: in Moscow the stoneworker from Rybreka saw ”the fruits of his labor” and the labor of all the stoneworking communities in their region; he saw where Karelian stone goes. While walking along the Red Square by the Mausoleum, Medvedev could always see his work (KP, June 8, 1967, p. 2).

A similar message is conveyed in an interview with a famous stoneworker from Rybreka village, Aleksandr Ryboretskii: ”When we are in Moscow, in Leningrad, in Petrozavodsk, or in other cities, we do not part with our Rybreka. We are proud to know that monument details in those cities are made with our own hands” (KP, November 4, 1967, p. 2). The newspapers published reports on every important result achieved by stoneworkers and about every notable destination to which the stone traveled. Such reports were probably designed to be motivational messages that would inspire the workers and persuade them to achieve better results.

My fieldwork data show that narratives on the rarity and durability of local stone are still important for the residents of Vepsian villages. A number of informants talked about the uniqueness of raspberry quartzite and gabbro-diabase, describing them as unusually hard and beautiful stones. ”If you pass a knife over a piece of stone, you will see a line on it—but it is not a line on stone, it is the knife being grinded,” as one respondent told me as proof of the unusual firmness of raspberry quartzite (Interview #21). Most of the people I talked to mentioned at least one or two of Karelian stone’s famous destinations—for example, Lenin’s Mausoleum, pavements in Red Square, or Saint Isaac’s Cathedral in Saint Petersburg. A resident of Rybreka, a former mining worker, recalled how during his studies in Moscow he proudly told other students when they visited Red Square: “This is our stone!” (Interview #9). Another former miner remembered his trip to Saint Petersburg where he saw the raspberry quartzite at Saint Isaac’s Cathedral and stated, “I can recognize this stone everywhere” (Interview #15).

Legends about the glorious past of raspberry quartzite and diabase were often contrasted with the current situation. Some respondents were upset about private companies wasting ”their stone” on graveyard monuments and felt that the stone is less important than it used to be. One former worker told me, ”We were producing spheres made of stone, they were used by plants all around the country. It was impossible to replace them with anything else. I don’t know what is going on now, when the quarry is closed. Maybe they have finally replaced these spheres” (Interview #1). The worker was upset about the fact that the unique product they previously made is not needed in the contemporary world, and they do not even know the reasons behind such a change.

Conclusion

The analysis of local perceptions of stone in Vepsian villages of Karelia shows that indigenous relations with extractive industries are more complicated than traditional binary notions suggest. Contemporary residents of Vepsian villages often view mining, nature, and their livelihoods as interconnected and interdependent elements. For residents of Vepsian villages, mining development on their territory was a consequence of its natural richness and the uniqueness of their stone. Thus, stoneworking may be considered an essential continuation of nature; the future of the villages, at the same time, to a large extent depends on the development of the mining industry. Conversely, mining influences nature, and many informants mentioned the drop in fish populations and rock dust in the air. However, even when talking about the negative consequences of mining, locals do not blame the industry itself but rather the private owners of the mines who are mostly not from Prionezhskii district and, as many locals see it, do not respect its nature enough. Residents of Vepsian villages wish there was more control over these companies—but mining, in their opinion, should be continued.

While the collective identity of local residents was in many ways formed through mining development, their bonds with nature remained strong: many of them spent their free time in the forest or by the lake, went fishing, or hunted while working in the quarries. The discourse of conquering nature and struggling with stone was very often present in Soviet-era newspapers, but both the mining industry and nature are important for the well-being of the contemporary residents of Vepsian villages, and they do not perceive them as being necessarily in opposition.

The stoneworking industry was often associated with hard labor and the risk of injuries; besides, being engaged with it meant working outside, often in extreme weather conditions. When so much is sacrificed for mining, it becomes extremely important to perceive not only its material benefits but also its symbolic meaning. The symbolism of mining was reinforced by newspaper articles that proclaimed the glory of Vepsian stone, the courage and strength of stoneworkers, the changes this industry had brought to the villages, and the importance of miners’ hard work. During interviews many of my informants mentioned the beauty and rarity of their stone, its famous destinations, and the glory it brought to their villages.

The ”mining identity” of northern Vepses and those who moved to the villages from other regions were preserved through time, despite all the transformations of the Soviet and post-Soviet periods. And today local residents do not view mining as something ultimately alien to their territory—indeed, they want to see it developing into the future. At the same time, as private companies currently operating in Prionezh’e invest much less in the district’s well-being than used to be the case when the state enterprise was functioning, many locals are nostalgic about the past when the life of the villages was more organized and they felt more involved in the work they were doing. Nowadays the residents of Vepsian villages feel the loss of jobs, infrastructure, and opportunities for young people; but above it all they feel that Prionezhskii district is losing its unique character related to the rare stone extracted here. As the descendants of famous mining dynasties or former workers of large, lively industries producing stone that was in demand in different parts of the country, they are now deprived of this local identity and symbolic sense of belonging.

References

- Argounova-Low, Tatiana. 2004. ”Diamonds: A Contested Symbol in the Republic of Sakha.” Pp. 257–265 in Properties of Culture—Culture as Property: Pathways to Reform in Post-Soviet Siberia, edited by Erich Kasten. Berlin: Dietrich Reimer Verlag.

- Arukask, Madis. 2014. ”Granitsa i sakral’nost’ v traditsionnoi veppskoi kul’ture.” Pp. 322–333 in Istoriko-kul’turnyi landshaft Severo-Zapada: Shegrenovskie chteniia. Sbornik statei. Saint Petersburg: Evropeiskii Dom.

- Blagoveshchenskii, Ivan, and Aleksandr Gariazin. 1895. Kustarnaia promyshlennost’ v Olonetskoi gubernii. Petrozavodsk, Russia: Gubernskaia Tipografiia.

- Bolotova, Alla. 2012. ”Loving and Conquering Nature: Shifting Perceptions of the Environment in the Industrialised Russian North.” Europe-Asia Studies 64(4):645–671.

- Bolotova, Alla, and Dmitry Vorobyev. 2007. ”Managing Natural Resources at the North: Changing Styles of Industrialization in the USSR.” Patrimoine de l’industrie 9(17):29–41.

- Cameron, Emilie. 2011. ”Copper Stories: Imaginative Geographies and Material Orderings of the Central Canadian Arctic.” Pp. 169–190 in Rethinking the Great White North: Race, Nature, and the Historical Geographies of Whiteness in Canada, edited by Andrew Baldwin, Laura Cameron, and Andrey Kobayashi. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press.

- Cooper, H. Kory. 2011. ”The Life (Lives) and Times of Native Copper in Northwest North America.” World Archaeology 43(2):252–270.

- Davidov, Veronica. 2013a. ”Ecological Tourism and Minerals in Karelia: The Veps’ Experience with Extraction, Commodification, and Circulation of Natural Resources.” Pp. 129–148 in The Ecotourism-Extraction Nexus: Political Economies and Rural Realities of (Un)Comfortable Bedfellows, edited by Bram Büscher and Veronica Davidov. London: Routledge.

- Davidov, Veronica. 2013b. ”Soviet Gold as Sign and Value: Anthropological Musings on Literary Texts as Cultural Artifacts.” Etnofoor 25(1):15–28.

- Donahoe, Brian. 2013. ”Identity Categories and the Relationship between Cognition and the Production of Subjectivities.” Pp. 137–154 in Nomadic and Indigenous Spaces: Productions and Cognitions, edited by Judith Miggelbrink, Joachim Otto Habeck, and Peter Koch. Surrey, UK: Ashgate.

- Dudeck, Stephan. 2008. ”Indigenous Oil Workers between the Oil Town of Kogalym and Reindeer Herder’s Camps in the Surrounding Area.” Pp. 138–144 in Biography, Shift-Labour and Socialisation in a Northern Industrial City—The Far North: Particularities of Labour and Human Socialisation, edited by Florian Stammler and Gertrude Elmsteiner-Saxinger. Proceedings of the International Conference in Novyi Urengoi, Russia, December 4–6, 2008. Retrieved June 25, 2016 (https://raumforschung.univie.ac.at/fileadmin/user_upload/inst_geograph/Book_Biography-ShiftLabour-Socialisation-Russian_North.pdf).

- Dudeck, Stephan. 2012. ”From the Reindeer Path to the Highway and Back—Understanding the Movements of Khanty Reindeer Herders in Western Siberia.” Journal of Ethnology and Folkloristics 6(1):89–105.

- Ellingson, Ter. 2001. The Myth of the Noble Savage. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Fefilat’ev, Iurii. 2007. Po sledam saamskikh tain (labirinty i seidy). Petrozavodsk, Russia: Skandinaviia.

- Gedicks, Al. 2001. Resource Rebels: Native Challenges to Mining and Oil Corporations. Cambridge, MA: South End Press.

- Hall, Stuart. 1990. ”Cultural Identity and Diaspora.” Pp. 222–237 in Identity: Community, Culture, Difference, edited by Jonathan Rutherford. London: Lawrence and Wishart.

- Hille, Kathrin. 2015. ”Hinterland Emerges as Microcosm of Russia’s Wider Structural Woes.” Financial Times, March 24. Retrieved June 25, 2016 (https://www.ft.com/content/619fcb64-d0c2-11e4-982a-00144feab7de).

- Ingold, Timothy. 2006. ”Re-Thinking the Animate, Re-Animating Thought.” Ethnos 71(1):9–20.

- Kostin, Ivan. 1977. Kamennykh del mastera. Petrozavodsk, Russia: Kareliia.

- Kirsch, Stuart. 2007. ”Indigenous Movements and the Risks of Counterglobalization: Tracking the Campaign against Papua New Guinea’s Ok Tedi Mine.” American Ethnologist 34(2):303–321.

- Kuznetsov, Vasilii, ed. 1905. Kustarnye promysly i remeslennye zarabotki krest’ian Olonetskoi gubernii. Petrozavodsk, Russia: Severnaia Skoropechatnia R. G. Kats.

- Li, Tanya Murray. 2000. ”Articulating Indigenous Identity in Indonesia: Resource Politics and the Tribal Slot.” Comparative Studies in Society and History 42(1):149–179.

- Mel’nikov, Igor’. 1998. Sviatilishcha drevnei Karelii (paleoetnograficheskie ocherki o kul’tovykh pamiatnikakh). Petrozavodsk, Russia: Izdatel’stvo Petrozavodskogo universiteta.

- Nadasdy, Paul. 2005. ”Transcending the Debate over the Ecologically Noble Indian: Indigenous Peoples and Environmentalism.” Ethnohistory 52(2):291–331.

- Nakashima, Douglas, and Marie Roué. 2002. ”Indigenous Knowledge, Peoples and Sustainable Practice.” Pp. 314–324 in Encyclopedia of Global Environmental Change, edited by Ted Munn. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons.

- Norin, Sergei. 1949. Izbrannoe. Petrozavodsk, Russia: Gosizdat Karelo-Finskoi SSR.

- Potakhin, Sergei. 2008. ”Shokshinskii landshaft kak areal rasseleniia severnykh (prionezhskikh) vepsov.” Pp. 116–120 in Granitsy i kontaktnye zony v istorii i kul’ture Karelii i sopredel’nykh regionov, edited by Ol’ga Iliukha and Irma Mullonen. Petrozavodsk, Russia: Karel’skii nauchnyi tsentr RAN.

- Pringle, Heather. 1997. ”Archaeology: New Respect for Metal’s Role in Ancient Arctic Cultures.” Science 277(5327):766–767.

- Salminen, Minna-Mari. 2009. ”International Academic Research on Russian Media.” Pp. 27–83 in Perspectives to the Media in Russia: ”Western” Interests and Russian Developments, edited by Elena Vartanova, Hannu Nieminen, and Minna-Mari Salminen. Helsinki: Aleksanteri Institute.

- Salve, Kristi. 1995. ”Forest Fairies in the Vepsian Folk Tradition.” Pp. 413–434 in Folk Belief Today, edited by Mare Kõivaand Kai Vassiljeva. Tartu: Institute of Estonian Language and the Estonian Museum of Literature.

- Stammler, Florian. 2011. ”Oil without Conflict? The Anthropology of Industrialization in Northern Russia.” Pp. 243–269 in Crude Domination: An Anthropology of Oil, edited by Andrea Behrendts, Stephen P. Reyna, and Günther Schlee. New York: Berghahn Books.

- Stammler, Florian, and Bruce Forbes. 2006. ”Oil and Gas Development in Western Siberia and Timan-Pechora.” Indigenous Affairs 2–3:48–57.

- Stoliar, Abram D. 2001. ”Milestones of Spiritual Evolution of Prehistoric Karelia.” Folklore 18/19:80–126.

- Strogal’shchikova, Zinaida. 2012. ”Respublika Kareliia.” Pp. 136–149 in Sever i severiane: Sovremennoe polozhenie korennykh malochislennykh narodov Severa, Sibiri i Dal’nego Vostoka Rossii, edited by Natal’ia Novikova and Dmitrii Funk. Moscow: IEA RAN.

- Strogal’shchikova, Zinaida. 2014. Vepsy: Ocherki istorii i kul’tury. Saint Petersburg: Inkeri.

- Strogal’shchikova, Zinaida, ed. 2015. Po derevniam vepsskogo Prionezh’ia. Petrozavodsk, Russia: PIN.

- Tilley, Christopher Y. 1994. A Phenomenology of Landscape: Places, Paths and Monuments. Oxford: Berg.

- Tilley, Christopher Y., and Wayne Bennett. 2004. The Materiality of Stone. Oxford: Berg.

- Titov, Iurii. 1976. Labitinty i seidy. Petrozavodsk, Russia: Kareliia.

- Trofimova, Liubov’. 2015. ”Zapylennaia Rybreka: Zhurnalistskoe rassledovanie.” Petrozavodsk govorit, February 9. Retrieved June 25, 2016 (http://ptzgovorit.ru/content/zapylennaya-rybreka-zhurnalistskoe-rassledovanie).

- Vinokurova, Irina. 1994. Kalendarnye obychai, obriady i prazdniki vepsov. Saint Petersburg: Rossiiskaia akademiia nauk.

- Vinokurova, Irina. 2006. ”Vepsskie vodianye dukhi: K rekonstruktsii nekotorykh mifologicheskikh predstavlenii.” Pp. 314–329 in Sovremennaia nauka o vepsakh: Dostizheniia i perspektivy. Petrozavodsk, Russia: Karel’skii nauchnyi tsentr RAN.

- Vinokurova, Irina. 2010. ”Voda v vepsskikh mifologicheskikh predstavleniiakh o zhizni i smerti.” Trudy Karel’skogo nauchnogo tsentra RAN 4:66–76.

- Vinokurova, Irina. 2012. ”Bannye obriady zhiznennogo tsikla cheloveka v vepsskom kul’turnom landshafte.” Trudy Karel’skogo nauchnogo tsentra RAN 4:57–67.

- Warnaars, Ximena, and Anthony Bebbington. 2014. ”Negotiable Differences? Conflicts over Mining and Development in South East Ecuador.” Pp. 109–128 in Natural Resource Extraction and Indigenous Livelihoods: Development Challenges in an Era of Globalization, edited by Emma Gilberthorpe and Gavin Hilson. Farnham, UK: Ashgate.

- Zassoursky, Ivan. 2004. Media and Power in Post-Soviet Russia. Armonk, NY: M. E. Sharpe.

Appendix 1. Interview list.

| No. | Respondent’s name and age | Date of interview | Place of interview |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Mikhail, 84 | July 24, 2015 | Shoksha |

| 2 | Galina, 78 | July 24, 2015 | Shoksha |

| 3 | Nikolai, 64 | July 25, 2015 | Shoksha |

| 4 | Aleksandr A., 47 | July 26, 2015 | Shoksha |

| 5 | Liudmila I., 75 | July 27, 2015 | Shoksha |

| 6 | Aleksandr E., 56 | July 27, 2015 | Shoksha |

| 7 | Svetlana, 62 | July 27, 2015 | Shoksha |

| 8 | Ven’iamin, 82 | September 16, 2015 | Rybreka |

| 9 | Valerii I., 56 | September 16, 2015 | Rybreka |

| 10 | Anna, 88 | September 16, 2015 | Rybreka |

| 11 | Faina, 63 | September 18, 2015 | Shoksha |

| 12 | Sergei, 48 | September 18, 2015 | Shoksha |

| 13 | Nina, 84 | September 21, 2015 | Rybreka |

| 14 | Vladimir K., 50 | September 21, 2015 | Rybreka |

| 15 | Evgeniia, 87 | September 23, 2015 | Rybreka |

| 16 | Valentina, 47 | September 23, 2015 | Rybreka |

| 17 | Liudmila A., 75 | September 25, 2015 | Kvartsitny |

| 18 | Nadezhda, 78 | September 30, 2015 | Kvartsitny |

| 19 | Vladimir I., 58 | February 24, 2016 | Kvartsitny |

| 20 | Liudmila L., 56 | February 24, 2016 | Kvartsitny |

| 21 | Valerii G., 53 | February 26, 2016 | Kvartsitny |

| 22 | Lidiia, 82 | February 26, 2016 | Kvartsitny |

Душа камня: символизм минералов в вепсских деревнях Карелии

Анна Варфоломеева – аспирант (PhD) факультета экологии и экологической политики Центрально-Европейского университета в Будапеште. Адрес для переписки: Department of Environmental Sciences and Policy, Central European University, Nador u. 9, 1051 Budapest, Hungary. varfolomeeva_anna@phd.ceu.edu.

Статья основана на полевом исследовании, проведенном при финансовой поддержке исследовательского гранта от Центрально-Европейского университета. Автор выражает благодарность двум анонимным рецензентам и редакционной коллегии Laboratorium за комментарии и предложения по доработке этого текста.

В статье рассматривается взаимодействие северных вепсов – коренного народа, проживающего в Республике Карелия, – с горным делом. Уже в XVIII веке карельские вепсы занимались добычей редких минералов (габбро-диабаза и малинового кварцита); добыча камня ведется в деревнях и сегодня. В работе предпринят анализ разнообразных символических значений, которые камень приобретает для современных жителей вепсских деревень, становясь одновременно источником трудностей, борьбы и гордости. Местные жители нередко рассматривают добычу камня и природу в их взаимосвязи, считая развитие горного дела естественным продолжением природных богатств региона. Данное исследование показывает, что традиционный образ жизни коренного народа, промышленное развитие и природа могут восприниматься как взаимосвязанные, сосуществующие элементы.

Ключевые слова: коренные народы; вепсы; Карелия; горное дело; символика камня

- Hereafter referred to as KP. ↩