Shopping at Sizomag: The Internet as a Potemkin Village of Modern Russian Penal Practice

Dina Gusejnova is a Leverhulme Early Career Fellow at the Centre for Transnational History, University College London. Address for correspondence: Gower Street, London, WC1E 6BT, UK. d.gusejnova@ucl.ac.uk.

Some of the theoretical premises for this essay are based on research into the place of prisoner of war camps in twentieth-century cultural history, which is supported by the Leverhulme Trust. I would like to thank Ol’ga Romanova and Petr Kur’ianov (Rus’ sidiashchaia), Anastasiia Ovsiannikova (Sakharov Center), and Nina Tagankina (Moscow Helsinki Group) for sharing their insights into post-Soviet Russian penitentiaries with me, although any errors in this essay remain my own. I also thank Ol’ga Romanova for allowing me to use photos from her archive in this essay. The contributions and support of Laboratorium’s editors were critical at various stages of this project. I thank them for their patience in allowing me to navigate this unfamiliar territory, even though any remaining shortcomings pointed out by them and the anonymous reviewers are still my responsibility.

The aim of this introduction and the ensuing discussion is to explore the role of the Internet in postsocialist Russian penitentiary practice and the social economy of punishment. The Internet has multiple functions in modern societies, as an information resource, communication tool, and instrument of government. This introductory essay is based on what could be called a digital phenomenology of the Russian Internet, supplemented by interviews with experts and a small selection of photographs from the personal archive of Ol’ga Romanova. As such, it provides only an outline of questions, with few tentative answers, which suggest how one might problematize the social significance of Internet-based services that have been offered in Russian penitentiaries since 2009 alongside the growth of the Internet as a medium of information exchange on penitentiaries. In sharp contrast to the language of modernization that governments and corporations tend to apply when they introduce digital technologies, their practical implementation in penitentiaries suggests at best uneven levels of modernity. Looking at the Russian case through the way it presents itself on the Internet, this essay and the following contributions by Judith Pallot and Yvonne Jewkes invite future studies to apply theories of “uneven modernity” and “normalization” in order to lay out critical perspectives for understanding the Russian case in comparative and diachronic perspective.

Keywords: Penitentiaries; E-Governance; Post-Soviet Studies; Uneven Modernity; Modernization Theories; Nation-State; Communications Technology; History of the Internet

The Internet has become a key medium through which conflicts and tensions in contemporary Russian society have become manifest. Internet resources, ranging from personal blogs to social networks to public information websites, as well as the streaming of live videos from courtrooms and private videoconferencing facilities, have been revealing to an increasingly large public aspects of penal practices in Russia that were previously invisible. This essay and the two other pieces in this discussion on “Penitentiary Systems in the Era of Internet Services” by Judith Pallot and Yvonne Jewkes present an initial contribution to the study of the Internet’s role in modern penal practice.

I would like to describe the method I use here as a combination of critical theory and “digital phenomenology.” While phenomenology is also a field of philosophy, which traces its origins to the work of Edmund Husserl, in the social sciences it has come to be used as a method of understanding the human that could be described as a way of grasping our structures of knowing through the forms that this knowledge itself takes (Schutz 1932). The Internet is an ideal example of such a structure and has been studied as such particularly by scholars of technology (Kim 2001) and the new subdiscipline of digital anthropology (Horst and Miller 2012). Not only it provides us with information and opportunities to access knowledge or goods, it also shapes the ways in which we access those things, the ways we interact, and how we think of ourselves and others. In the stage of modernity we have now reached, it is misleading to suggest that “being” has become inseparable from “screen,” as Stéphane Vial (2013) has recently put it; rather, the ruptures between “screen entities” and different levels of real experiences disclose the profound unevenness with which conceptions of the human are formed in a modern society such as post-Soviet Russia.

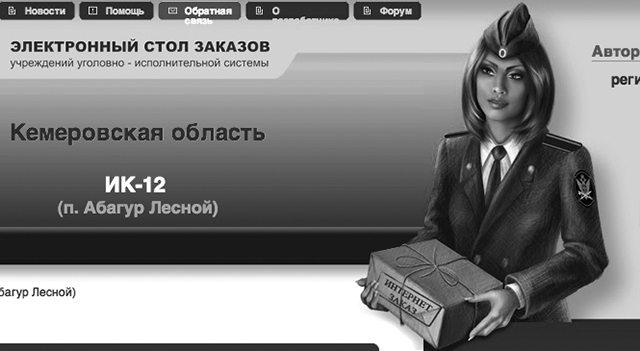

The image in Figure 1 shows a female officer of Kemerovo Correctional Colony No. 12 (IK-12, ispravitel’naia koloniia) delivering an old-fashioned parcel, banderol’, tied with a string and wrapped in characteristic brown paper, with the words “internet zakaz” (Internet order) printed on its side. The page that is supposed to be an online shopping facility features a shampoo from a well-known Russian brand as its only product on offer. Although there are other, more diverse online shops in Russian prison facilities closer to Moscow, the state of this online prison-store-in-the-making in the Siberian region of Kemerovo captures particularly aptly the uneven character through which Internet commerce has permeated the Russian penitentiary.

The Internet, an electronic resource that has far surpassed earlier technologies such as television, is a global electronic communication facility that constitutes a qualitatively new tool of information exchange for images and texts. In the 1990s, a number of optimistic prognoses suggested that the Internet would reduce the powers of nation-states as a result of processes such as the government deregulation of communications (Cairncross 1997; Dizard 1997). Indeed, in some respects, it became possible even for individuals, like, in the Russian case, prominent bloggers Aleksei Navalnyi or Anton Nosik, to reach a level playing field with government resources and the most capitalized private branches of the broadcasting industry. Yet when it comes to the impact of the Internet on nation-states, ten years on, a more complicated picture has emerged, in which both the nation-state and substate private and supranational corporate actors have come out stronger (Chadwick 2006; Castells 2009). This situation forces us to return to earlier warnings from social theorists that the end of the (nation-)state, which social theorists predicted, has never arrived (Mann 1993). Despite being a global technology, the actual content and form of such exchange remain vastly different in global perspective.

Looking at penitentiaries, the communication revolution has received largely negative evaluations. Among scholars of penal practice, the Internet has attracted attention primarily in two respects: as an instrument of crime and as an instrument of control (Jewkes 2007b). As a communication tool, the Internet lends itself to criminal activity and calls for a reconceptualization of notions of victimhood and agency (Jewkes 2003). The criminal capacity of the Internet appears to be particularly great when it comes to nonverbal communication and the use of photo and video footage. Secondly, as a communication tool that is particularly potent in managing the relationship between governments and population groups, the Internet has attracted attention from social critics and prison reformers. In penitentiary practice, prison regimes have come to see the Internet as another sphere in which prisoners can and should be isolated from society, something which advocates of prison reform have discussed as problematic (Jewkes 2011:237ff.). Punishment is becoming an integral part of what Nils Christie has called “crime control as a product” (1993:93) or what David Garland (2001) described as the “culture of control.” Seen in this light, the social and political architecture of the World Wide Web shapes not only the concept but also the practice of punishment in Russia. As a source of knowledge about penitentiaries, the Internet has become an instrument for producing and consuming information about incarceration as well as empathy with the inmates or with the administration. But it is also a tool of surveillance, control, and identity management for individuals, groups, and governments.

In particular, the Internet has become a new platform on which governments can communicate with and exercise control over populations through what is often called “e-governance” (Bellamy and Taylor 1998; Meier 2012). We can differentiate between several aspects of electronic governance to which the Internet lends itself. One is the use of digital technologies and electronic intelligence by governments for purposes of ordering populations. A second form of electronic governance entails the use of such technologies by corporations for the sake of profit. A third form relates to civic uses of new technologies for politics, from communal to transnational and global in scale. Finally, we can speak of personal uses of the Internet as ways of fashioning the self, such as keeping a diary or pursuing various pleasures or forms of knowledge. The function of the Internet in prisons captures all four dimensions in a complex entanglement with each other. However, because the government has disproportionate control over both commerce and communication in the penitentiary, there is the danger of the emergence of a pernicious cartel—between governmental and corporate forms of e-governance, at the expense of civic forms of e-governance.

In this essay I want to identify a further aspect in which the Internet can be of interest to scholars of penal practice. As Internet technologies have become more socially diffused, making it easier for private individuals to upload and share information, the function of the Internet as a tool of control has also changed. Control through media such as radio and television, which previously had been the prerogative of governments or broadcasting corporations, has not only become participatory, suggesting that each Internet user can also become complicit in the exercise of control. Thanks to its social character, the Internet also manifests and activates new forms of group identity. The metaphor of the Potemkin village, the intricate system of show façades that Prince Grigorii Potemkin allegedly had designed to impress Catherine the Great on her visit to the Crimea, has been used to describe post-Soviet Russia before (Allina-Pisano 2008). Here, the metaphor is used to refer to the façades of modernization that are specific to the Internet as a medium of commerce and communication. Using the resources and ideas embedded in the Internet itself, how might we begin to approach a critical inquiry into the logic of present-day Russian penal practice?

My study of the impact of the Internet on conceptualizations of punishment, supplemented by interviews with experienced observers of penitentiaries as well as former inmates, can only serve as a preliminary foray into this field. Two pioneering sets of critical and empirical studies are fundamental for any exploration of the modern Russian penitentiary, as well as the question of the Internet in modern penal regimes. The first is the work on the Russian penitentiary by Judith Pallot and Laura Piacentini, who engaged with questions of Russian exceptionalism in comparative and diachronic perspective through the prism of the penal periphery as a key concept of Russian carceral theory (Pallot and Piacentini 2012). The second is the work on the place of the media in modern theories and practices of punishment by Yvonne Jewkes, which concerns mostly modern British cases and problematizes the ambivalent function of the media in society in this sphere (Jewkes 2003, 2007a, 2007b, 2011). What connects both sets of work is not only a shared interest in identifying penal studies as a field of understanding modernity but also the attention to autoethnographic and critical observations of the pathways by which we can acquire knowledge of penal geographies that is not itself complicit in the exercise of punishment. The Internet as a window on the penitentiary opens up a way for an analysis of penal practice not as a detached object of study but as a cultural product that each author coproduces through extracting information from the Internet.

Without sharing my observations of the Russian case, which are outlined here, I approached Judith Pallot and Yvonne Jewkes with a list of questions, and their answers follow this essay. The general question I wished to ask them concerned how new technologies and services facilitated by the Internet affect the relationship between state and society in the sphere of criminal punishment in modern societies. Does it lead to a “normalization” of the penitentiary both among the incarcerated and the free population, in the sense of making the penitentiary a regular and accepted form of life? Or does the Internet “humanize” the experience of incarceration for prisoners and their families? Does the penetration of the Internet into prisons transform inmates—or at lease their representation in the media—from their long-standing position in the Russian society as laborers into consumers? To what extent does the introduction of Internet services and Internet-mediated discussions of prisons change the construction of gender expectations and stereotypes? What is the commercial function of the Internet in construing the relationship between governments, prisoners, and the “free” segment of society? This essay will provide some context and theory for this discussion and sketch out possible directions of further study through the concept of “uneven modernity.”

Unevenness and Post-Soviet Society

The concept of “unevenness” in studies of modernity, inspired by work that revisits classical critiques of political economy through global human geography, helps to grasp the observation that modern societies like Russia, which have experienced technological advancements, can nonetheless be fragmented into multiple, not always overlapping communities that enjoy radically different and partial levels of access to the goods and services associated with modernity. After the breakup of the Soviet Union, the traces of a centrally managed economy but also a rigid system of penal labor were gradually eroded and replaced by a mixture of authoritarian government and anarchic forms of capitalism. This perspective on the cultural dimension of uneven modernization has already yielded new research in studies of societies such as contemporary China (Gong 2012). In the case of Russia, historians have observed “uneven modernity” as a feature that connected imperial practices of “internal colonization” with socialist practices of hegemony and that persist in the postsocialist era (Smith 1984; Harvey 2006; Etkind 2011). A notable example for this is the patchy use of electronic means in different domains of governance.

In the sphere of punishment, the concept of unevenness might be used to explain the simultaneous coexistence of forms of punishment that are usually associated with earlier historical periods. As David Garland and others have indicated, the coexistence of archaic, spectacular forms of punishment with modern, correctional forms was unforeseen by classical theorists of the penitentiary (Garland 2001). Classical theorists of modern punishment, notably Émile Durkheim, distinguished between premodern and modern forms of punishment by suggesting that the public visibility of punishment was a characteristic of premodern societies with their “mechanical” forms of solidarity (Durkheim 1899–1900). These tend to opt for deterrent uses of punishment as a spectacle; conversely, modern societies tend to see the function of punishment in the correction of deviant behavior and the restoration of normal social life.

Between the eighteenth and the twentieth century, Europe’s modernizing societies tended to distribute their populations in remote penal colonies, parallel to the way that slave labor was used in areas removed from the metropole. Thus, France’s penal colonies were located in the Caribbean, which was also where its slave labor was based; British penal colonies were based in North America and Australia (Williams 1944). According to early twentieth-century Marxist critics of punishment, the function of modern penal institutions was to serve as sources of labor exploited for surplus (Pashukanis 1932; Rusche and Kirchheimer 1939). Indeed, large socialist industrial projects such as Belomorkanal were made possible largely due to the labor of prisoners. Similar observations have been made of the use of transportation and penal labor in the European overseas colonies (Barbançon 2003; Toth 2006).

By contrast, postmodern systems of punishment contain elements of both, and the Internet in particular constructs new types of spectacle, as well as new modes of isolation from and connection with the outside world. Postmodern societies appear to reverse these tendencies: their imprisoned population tends to be concentrated in high-security, privately run prisons, which can be located both in urban centers and in remote areas. It is their “free” citizens who are encouraged to move wherever the market may take them, including to the areas of intense exploitation of free labor.

The dissociation of penal regimes from regimes of production allowed critics of late modern systems of punishment, notably Michel Foucault, to point out that both the “corrective” and the “productive” functions of punishment in modern systems are only their apparent functions (Foucault 1975). The real function of punishment is rather similar to the function of science in the modern world: it is to establish distinctions between the normal and the pathological in a society. While the apparent function of punishment is to punish (or at least to respond to and, perhaps, prevent future) crimes, the real function of punishment is to create the idea of a social norm: in terms of gender, race, or notions of maturity and health prevalent in a given society.

The way contemporary Russian penal colonies are both embedded in and excluded from the national and global political economy fits this model of penal practice as an institute of normalization very well, particularly when it comes to the unevenness and contradiction in terms of its place in Russian society. At first sight, the Russian penal colony appears to be an island (or archipelago) within a nation-state, as famous classics of twentieth-century Russian literature have argued (Margolin 1949; Solzhenitsyn 1973–1975). According to the economist Anton Tabakh, from the point of view of economic effectiveness prisons continue to be “mysterious islands” (with reference to Jules Verne’s eponymous novel) because they are an irrational feature of the modern economy. The rationale behind the present system, which allocates the majority of prisoners to colonies based on strict labor regimes, fails in its reforming purpose because only 23 percent of the Russian prison population (or between 30 and 36 percent, according to other sources) has any kind of employment, and even those who are employed have few incentives for work and thus self-betterment.[2] The only economic sense the Russian penal system makes is that, due to a currently interned population of around 680,600, penal administration is one of the government’s largest employment sectors, employing 310,600 people, roughly equivalent to the number employed by the Russian postal service—390,000.[3] In the 2013 federal budget, 215 million rubles are allocated to the financing of federal correctional institutions, a figure that is comparable to the budget for national healthcare (282 million rubles). Tabakh’s conclusion is that real humanization of the “island” would involve substantial reform of its management as an economic system that does not cost the taxpayer this kind of expense without achieving the goals of reeducation of prisoners and economic sustainability (Tabakh 2012).

According to Oleg Korshunov, head of the financial and marketing division of the Federal Penal Service (FSIN, for Federal’naia sluzhba ispolneniia nakazanii), in 2013 prisoners produced up to 100,000 different items worth up to 30–34 billion rubles (Veselov 2013; Telekanal Dozhd’ 2013). Currently, on FSIN’s own website[4] products are classified by the type of material they are made of, for example, production for the logging industry (2.16 percent of total), metal (16.28 percent), services (18.95 percent), light industry (19.8 percent), and the “production of goods for national consumption.”[5] But a clearer way to categorize these products for analytical purposes would be in terms of their place in the national and global markets. The first, most visible category of products comprises things that are used to maintain the system of FSIN: uniforms and shoes for police and the FSIN administration, but also barbed wire and even buses that are used to transport prisoners (the so-called avtozaki). The second category, also visibly advertised on some FSIN websites, comprises items destined for a limited market of those who want to support FSIN production; it includes souvenir items, such as chessboards and backgammon sets.[6] The third category, finally, is products that are designed for a much larger and less visible market, which involves agreements between the FSIN administration and private entrepreneurs. According to Korshunov, it is this last sector that the FSIN administration has been trying to centralize since January 2013.

Russia’s current Federal Criminal Code (Ugolovno-ispolnitel’nyi kodeks) justifies its activities in the liberal language of correction and reintegration. The “correction of convicts” is defined as the effect of forming among them “respect for the human being, society, labor, norms, rules, and traditions of cohabitations and the stimulation of lawful behavior.” The means of attaining this are a given order of punishment (rezhim), including education, professional training, and “social influence” (Ugolovno-ispolnitel’nyi kodeks 1997, Article 9). At the same time, as Pallot and Piacentini (2012) show, the Federal Penal Service, where such reeducation supposedly occurs, still bears the mark of forced labor that was embedded in the penal system of the Soviet Union, which was much less interested in reintegration than in isolation from and long-term removal of criminal populations from its political heartlands. Despite modernization in other areas, Russia has maintained its penal peripheries, and technological innovations such as telephones, television, and now the Internet have served as mere partial “fixes” to this system. In fact, Pallot and Piacentini suspect that the construction of distance, following Henri Lefebvre (1991), is at the very heart of the specific form of punishment that distinguishes the Russian penal tradition. They give at least two criteria for measuring distance in terms that make it relevant to human geography. One is the distance of prisoners from their homes; on this count, the production of distance as an instrument of penal power appears to have gone down, with 41.3 percent of all prisoners in the Soviet Union being sent out of their home regions in 1989, and only 33.4 percent of men and 17.7 of women sentenced to another region in 2009 (Pallot and Piacentini 2012:47). The other concept of distance as a category relevant to human experience is the hierarchy of regions that emerges if we consider the factor of density of prison population by region, which produces a sort of “negation” of classical center-periphery relations in Russia. By this token, the center of governance, Moscow, has a characteristically low density of prison population; conversely, the peripheries of governance in the North and Far East turn out to be leaders when it comes to the density of their penal population (57).

The modern Russian prison system, with its emphasis on reeducation in the penal periphery, then, seems to be a “peculiar institution” (Stampp 1956). Like slavery, it exists in and is upheld by societies of rational beings, although it is not even in the economic (let alone in the human) interests of these societies. Considering its isolation from the national market, where FSIN is a closed system or island of its own, the Federal Penal Service appears to lack economic sustainability. While some prison colonies have insufficient opportunities for work by inmates—which is true particularly of penal colonies for men, formerly set up for such industries as logging—other colonies, particularly in the clothes manufacturing sector for women, have been found to breach EU norms of labor regulations.

The women, who are forced to work sixteen-hour days, often more than five days a week, are paid an average of 1,200–1,300 rubles per month (the equivalent of about $40) (Lenta.ru 2013). The account of forced labor in Correctional Colony No. 14 (IK-14) in Mordoviya by Nadezhda Tolokonnikova, the political activist and member of feminist punk band Pussy Riot, serving a prison sentence since August 2012 on charges of hooliganism for a performance at Moscow’s Christ the Savior Cathedral, has triggered investigations into where the income of surplus work done by inmates in women’s prison colonies might go (Tolokonnikova 2013).[7] From the perspective of the prisoner, the monthly pay of between 29 and 1,000 rubles for a sixteen-hour working day, during which prisoners produce uniforms for the police, suggests that profit from this labor goes elsewhere (Veselov 2013).

The full extent to which Russian prison colonies are embedded in national and transnational markets remains to be analyzed in more detail, but it is clear that prison colonies are far from being closed or irrational economic systems. They may be unable to sustain themselves, but they certainly bring profits to some groups. Investigative journalists who followed up on Tolokonnikova’s allegations found out that in the case of this particular colony, part of the clothes output was sold on the global market through the Moscow and Saint Petersburg–based company Vostok-Servis, which specializes in heavy duty work clothing and ships the products it collects from prison colonies such as IK-14 via contractors to global distribution systems (Maetnaia and Petelin 2013b). While officially the production goes towards sustaining government services and supplying clothes for government civil servants such as police, prisoners also appear to work as forced laborers in a transnational economy of production and distribution. Thus isolation within certain segments of national economies, such as the existence of penal colonies which provide clothes for the administration of penitentiaries or police, may well coexist with integration in a particular segment of the international market (as in the case of Vostok-Servis) (see, e.g., Kortunova 2013; Rozhkova 2013). A full empirical investigation of the economic inclusion of Russian penal colonies in global markets is yet to be done. But at this stage, a closer look at the more visible instruments of government implemented in modern Russia already looks like a cautionary tale concerning premature assumptions of the linkages between modernization, e-governance, and democracy, as the UN special report on e-governance tends to present it (United Nations 2012).

Deceptive Proximity and Real Distance

As Pallot and her colleagues have shown, geographical distance and penal labor are embedded in Soviet and post-Soviet, national and transnational economies of violence at the same time (Pallot 2005; Pallot and Piacentini 2012). Taken together, they suggest that distance as a socially constructed factor continues to play a role in postsocialist Russia, particularly in the sphere of punishment. The question is to what extent this effect is softened when, as in some Russian prison colonies, prisoners get partially reintegrated into the social web of the Internet. The unevenness of their integration in social and geographic terms is another dimension of “uneven modernization” that needs to be considered in more detail. As studies with prison populations in Western Europe have shown, distance from home is the factor that makes reintegration of former prisoners in society particularly difficult, and in some cases the Internet can be used to resist the production of distance in prisons (Corston Report 2007; Scott and Codd 2010:168; Pallot and Piacentini 2012:250). It remains to be seen to what extent the introduction of Internet services to prisons in Russia changes the character of punishment, but the double periphery constituted by remote location and no access to the Internet appears to work in exactly the opposite direction if the intended goal of such internment is indeed future reintegration in society.

The Russian government first introduced Internet-based government services as a priority in 2009, when the office of the president began employing the paradigm of e-governance to describe the integration of new electronic technologies for the exercise of government and the availability of government services by electronic means. A special presidential council for technological modernization was set up, which comprised not only politicians but also leading entrepreneurs in this field, such as the Kaspersky family, who designed the famous eponymous antivirus software used worldwide.[8] According to the United Nations E-Government Survey 2012, Russia is now among the “emerging leaders” in this field in Eastern Europe and globally, even though it lags behind Western European countries (United Nations 2012). The idea that the Internet could draw a larger percentage of the electorate into an active participation in civic and political life fits into this narrative of modernization as progress that is measured by degrees of participatory forms of self-government. However in Russia, far from enabling greater levels of democratic accountability or civic autonomy, new technologies are used by governments for purposes of control over populations.

In the sphere of penal justice, the Russian Criminal Code was amended in June 2012 to include references to lawful use of “electronic means of surveillance” (Ugolovno-ispolnitel’nyi kodeks 1997, Article 83). By contrast, Pravila vnutrennego rasporiadka ispravitel’nykh uchrezhdenii (Rules of internal organization of correctional facilities) expressly forbid any use of electronic technology by prisoners.[9] When it comes to prisoners’ rights, the Rules speak exclusively of letters posted through a physical mailbox or even dispatches by telegraph. A supplement, drafted in February 2009, itemizes “articles [of clothing] and items, foods, which convicts are prohibited from carrying with them, receiving in parcels or packages, or acquiring”; according to this document, convicts are expressly not allowed to possess personal computers (which item 13 of the supplement 1 defines as elektronno-vychislitel’naia tekhnika), even though the document is silent when it comes to the use of computers in specially allocated educational rooms. A special amendment to this provision of February 2012 suggests that lawyers are allowed to use cameras as well as audio and video technology during their meetings with clients in prison colonies.

While the Code and the Rules contain no references to the Internet, there is plenty of clarity when it comes to other media, including radio and television. For instance, Article 94 of the Code, last amended in 2001, discusses regimentation of “watching of films and television, listening to radio programs by those sentenced to deprivation of freedoms” in dedicated “educational rooms” and during times not occupied by correctional labor or scheduled sleeping hours. Article 92, similarly, discusses the regulation of permissible telephone conversations, which are to be limited to 15 minutes per session and could be restricted to as few as six conversations per year, depending on the regime of incarceration. In my discussions with former prisoners, I found that in practice there was great disparity in terms of access to communication technology in correctional institutions.

According to some observers of modern penitentiary systems that I have spoken to at the Sakharov Center in Moscow, the Moscow Helsinki Group, and “In Defense of Prisoners’ Rights” Foundation (Fond “V zashchitu prav zakliuchennykh”), the Internet is unavailable to many inmates in practice, or its use is not officially sanctioned. In places where it exists unofficially (due to illicit mobile phone use, for example) it is used by prisoners primarily for social networking (on websites such as VKontakte, Facebook, or Odnoklassniki), as an informational and pornographic resource, or, more rarely, for shopping and managing finances. Speaking recently to a group of former prisoners, I found that they were, understandably, particularly reluctant to provide detailed information about illicit access to the Internet that inmates might have. But others, such as former prisoner and now social activist Petr Kur’ianov, suggested that access to Internet facilities, even where possible, was in practice limited due to the strict regulation of prisoners’ time, which leaves at best a total of half an hour of private time that could be used for personal hygiene or acquiring food and that prisoners are therefore unlikely to spend trying to get access to the Internet, books, or even television in the rooms dedicated to leisure. [10]

According to investigative journalists, the spread of Internet technologies in Russian prisons is linked to a “commercial turn” in penitentiaries that can be traced back to 2009, when Aleksandr Reimer was appointed head of FSIN (Maetnaia and Petelin 2013a). In 2013, he was prosecuted on charges of corruption, involving the production and supply of electronic tags to prisons (Petelin and Barinov 2013). As Valentin Bogdan told me in an interview, it was under Reimer that both state- and privately run services for shopping for and communicating with inmates were first set up. As another feature of “uneven development,” the prison stores seemed attractive to users because they allowed the provision of goods that the Criminal Code and the Rules normally exclude from the list of permissible items. Such items that are available at online stores for prisoners but cannot be sent by other means range from toilet paper and toothpaste to items of feminine hygiene, cigarettes (which normally are broken up when passed by hand), electric heaters, and specialty foods (Petelin and Maetnaia 2012). The initial establishment of prison online shops coincided with increased consumer use of digital money and web-based financial services (Voronina 2013).

The overall picture of the Internet is that as an instrument of modernization its spread across the penal sector of post-Soviet Russia has been uneven. But aside from the fact that it is not available everywhere, what could be the ethical implications of unevenness precisely in this area of technological development? Looking at another level of unevenness in post-Soviet Russia—the relationship between proximity and distance in its penal logic—I suggest that such implications are greater than one might think.

Of particular importance for understanding uneven levels of modernization in the present context is the fact that among the free residents of different Russian regions, Internet usage is particularly low in those areas on the periphery that have a particularly high density of prisoners, such as Mordoviya and Perm’, which Pallot and Piacentini (2012) call the “penal heartland” of Russia. Being sent to one of these regions, then, multiplies the effect of isolation particularly for those prisoners whose origins are in the intensive zones of Internet usage, because informational isolation that comes with incarceration is further augmented by the fact that the local population among whom the camp is located is disconnected from the virtual segment of Russian public life. According to some estimates, the share of Russians who regularly accessed the Internet in 2012 was 57 percent of its 143 million population (Interfaks 2012). Yet in geographic terms, this high level of Internet participation shows great unevenness in distribution. In cities such as Saint Petersburg and Moscow, around 68 percent of the population use the Internet on regular basis. By contrast, in remote regions on the Far East, like Tuva, only 30 percent of the population go online regularly (Goncharov and Lebedev 2011; Redaktsiia FOM 2013). It is these regions that also have a disproportionately high level of incarceration per capita. Prisoners in remote areas are twice removed from Russia’s modernization—by geographic and by punitive means of exclusion.

Given the unevenness in actual distribution of Internet services, the glaring gap between unofficial and official knowledge about the Internet in penitentiaries, and the disproportionate presence of highly educated prisoners in Internet discussion rooms, how might one approach the study of the Internet in the Russian case? I suggest that one step toward it is through a phenomenology of Internet services that FSIN officially provides, which can be juxtaposed with photographs and reports about prisons and penal colonies. Together, they form an ambivalent picture of what I would call “normalization,” using a concept which historian Mary Fulbrook developed for the experience of life in the GDR. She describes it, contrary to its common-sense meaning, as an “intrinsically relational, comparative term, with an element of movement or time frame: returning to, or making conform to, or aspiring to, some conception of ‘normality’” (Fulbrook 2009:3). In the context of West Germany, where the term was widely applied, it was associated with life after Nazis’ defeat and the “economic miracle” of the postwar years, during which an ideology-free life became possible. By contrast, as she argues, drawing on Kieran Williams (1997) and Zdeněk Mlynář (Brus, Kende, and Mlynář 1982), in the context of the GDR and Eastern Europe, “normalization” was a transitive and top-down process, by which governments were establishing hegemony over populations, particularly when it came to Soviet hegemony over Eastern Europe.[11] Normalization, then, is the double process by which governments make societies conform to certain norms and through which individuals and groups, in turn, are conditioned to experience their life as “normal.” It is also a term that describes a particular period in the life of a society in which a certain collective intention is formed to return to normality after what is presumed to be a period of rupture. In the case of modern Russian penitentiaries, this rupture was constituted by seventy years of Soviet rule during which the country lived under the ideological banner of alternative modernization, but in fact ended up lagging behind, particularly with respect to the “information revolution” that had taken over the rest of the developed world in the late 1980s. Constructing images of “normality” is one of the senses in which Internet services are Russia’s new Potemkin villages.

The Internet and the Notice Board: On the New Economy of Nerves

The Internet as a social medium introduces wider audiences to standards of “normality,” which includes the “normalization” of life in penitentiaries. Government services use the press services of FSIN to show outwardly that penitentiaries are a normal part of social life and that they are humane correctional facilities aimed at reintroducing prisoners into society; yet internally, the regime enforces its arbitrary rules with notices attached to walls by hand, which communicate to prisoners and their families that they continue to be embedded in society and ought to learn the norms that they are being accused of having broken.

2a

2b

2c

2d

2e

The new selective visibility and openness of punishment as correction, in which we can all observe and read about abusive practices in prison colonies whilst being told that all is normal in the penitentiary, introduces a new quality: this is not just medieval spectacle as deterrent, and not modern isolation as correction, but a new form of punishment, a virtual and even interactive spectacle of dehumanization. The Federal Penal Service prides itself on its own Youtube and Rutube channels. It collects a record of its own appearances on television. The FSIN website also contains references to a select number of web-based communities of prisoners and their families.

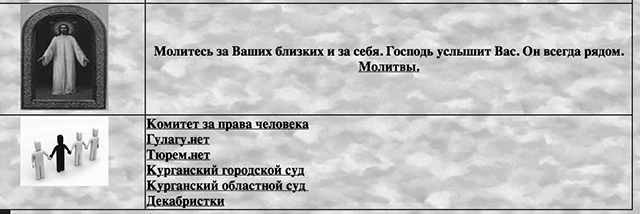

The overcoming of temporal and spatial obstacles is a major theme of these websites. A much repeated trope is that these sites promise users to save them “the expense of time and nerves,” some even “the expense of time, money, and nerves” and the hassle of having to travel long distances to visit incarcerated relatives.[13] On one website each element in the list—time, money, and distance—is documented with illustrations, featuring a clock, images of money, and images of old ladies carrying large bags across a railway track (see Figures 2a, 2b, and 2c). The last one supposedly illustrates how relatives of prisoners had to carry goods to their loved ones before the Internet became available. This combination of phrases such as saving time, money, and nerves is a cliché in commercial advertising, but it acquires sarcastic connotations when it comes to addressing the relatives of prisoners, as if being in prison and supplying a prisoner with goods were a regular part of one’s economy of life. There is even a way in which Internet services, such as the parcel service Peredachka45, indicate the existence of different temporal time frames: One line (see Figure 2d) suggests, for instance, that prisoners “pray to God” for their next of kin, and includes a hyperlink to prayers as well as the image of Jesus. The next line contains an abstract drawing of three white mascots holding a red mascot by the hands and links to counseling and advocacy networks and the social network Dekabristki, named after the famous wives of the men behind the Decembrist uprising in the history of nineteenth-century Russian liberalism. Yet another line on this website suggests that relatives might also want to send “humanitarian aid” to their relatives behind bars; the illustration chosen for this action is a giant flat-screen TV (Figure 2e).

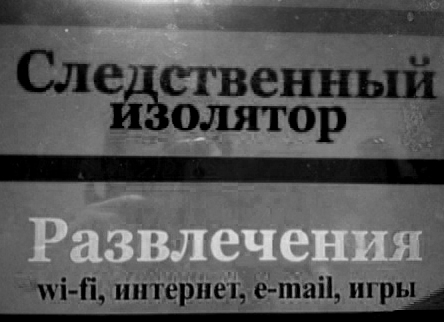

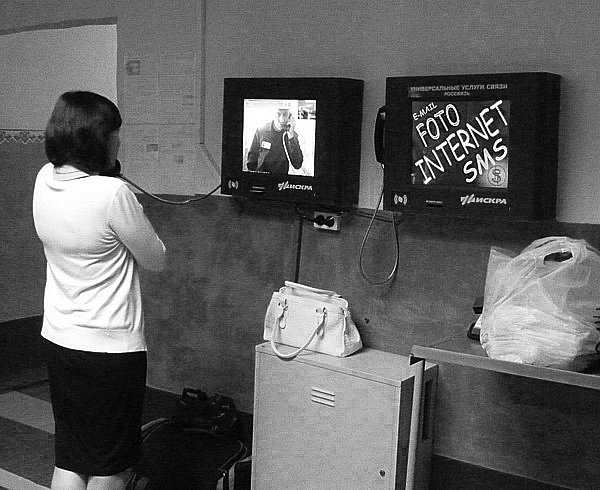

The simulation of normality through references to modern gadgets and technologies is also attempted in advertising for Wi-Fi and Internet as entertainment in pretrial detention zones (as in Figure 3), which present Internet services in a way that is completely disconnected from the idea of human contact.

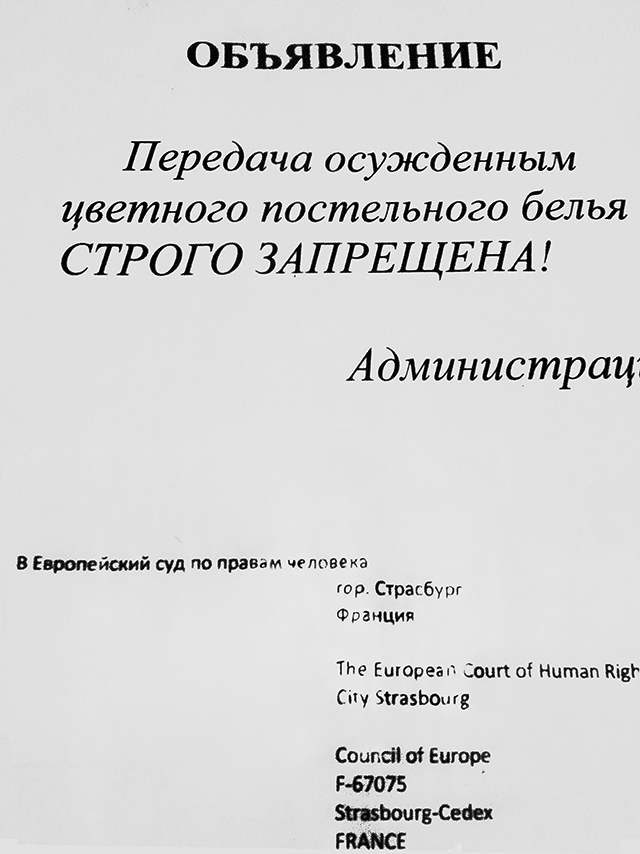

Such signs of modernization, however, coexist in modern prisons alongside entirely nontechnological, as well as seemingly absurd—yet, from the point of view of administrative consequences, dead serious—notices. In Figure 4, the notice that “The handing over to convicts of colored bed sheets is STRICTLY PROHIBITED—The Administration” is immediately followed by the address of the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) to which all complaints should be sent. Such notices not only highlight that the real instrument of governance in prisons is the hand-posted notice (even if it is printed on a laser printer), but they also indicate that the Russian detention center itself defers all complaints not to domestic committees for human rights or Russian high courts but directly to the ECHR, indirectly deferring ultimate sovereignty to this court. Indeed, Russian appeals constitute the majority of all human rights appeals cases to the ECHR. Thus in 2012, over 22 percent of appeals came from Russia, followed by 13.2 percent from Turkey, 11 percent from Italy, and 8.2 percent from Ukraine (European Court of Human Rights 2013:8). Behind the façade of normalization, where Wi-Fi is part of “entertainment,” we can thus still discern the profound sense of disorientation, as the penal institution defers its own authority to the European Council, a legal body located outside of the country’s state borders.

E-Letters to Prison and Scanned Letters from Prisons

Another contrast between the digital façade and real power is in the sphere of communications. The first virtual system of communication with prisoners called FSIN-pis’mo was introduced in Saint Petersburg’s infamous Kresty prison in 2009.

The page, surrounded by a colorful fringe reminiscent of an international letter, invites users to send e-mails—and even pictures—to prisons currently covered by the service. An online counter keeps a minute-by-minute record of how many letters have been delivered. Such e-mails are treated like regular letters: once you have paid your fee, they are processed by censorship authorities and passed on to the addressees. Sending each letter costs 50 rubles ($1.5) per page if you do not want a reply or 100 rubles if you want to request a reply from the recipient, with 25 rubles extra per picture. These services, notably, are only available in a small selection of prisons and prison colonies, in 17 regions out of Russia’s 83.[14] There is, unfortunately, no official data available on usage of the Internet in this way in Russian prisons and colonies. But FSIN does advertise that a large number of prison colonies now also subscribe to a range of videoconferencing services similar to Skype, such as VideoRendezvous (www.videosvidanie.com) or HomeConnection (www.rodnayasvyaz.ru).

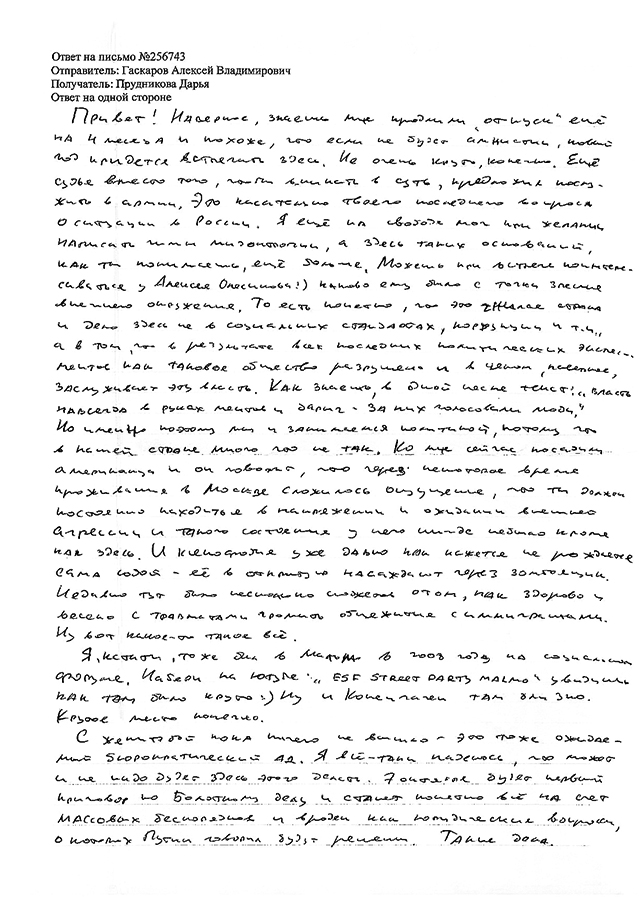

Elements of virtual communication such as these suggest that the “penal periphery” described by Pallot and Piacentini (2012) might indeed be partially overcome through technology. However, when it comes to the way such services are arranged, we have to consider the asymmetries of power that inform them. Payment for services such as videoconferencing and e-mail is essentially dependent on relatives in the free world. Moreover, most frequently, replies from prisoners continue to reach a wider public in the form of scanned letters handed to lawyers during their visits. This dialogue between prisoners and their relatives is visibly asymmetrical: each typed e-mail gets a handwritten letter in response (see, for example, Figure 7 that shows a handwritten letter from one of the defendants in a case against anti-Putin protesters).

The geographic distance of the penal periphery and the isolation of prisoners in detention facilities may be overcome by technology, but it also continues to be maintained due to the symbolic distance of digitally processed versus handwritten communication.

E-Shopping for Inmates: Government Holdings and Private Companies

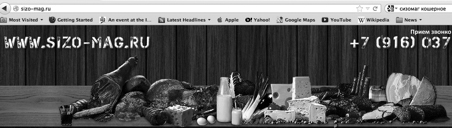

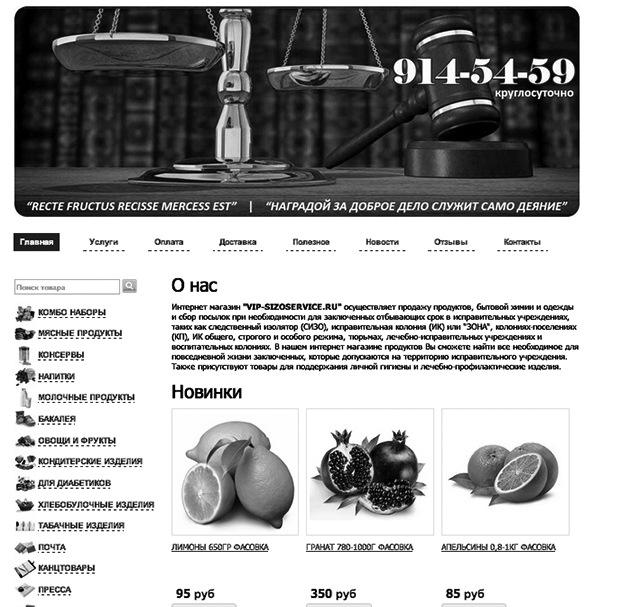

In the Russian media, the introduction of Internet services by governments is often presented as a value-free and ideology-free expansion of service. It is a feature of modernization in the positive sense, allowing more people to exchange more goods and ideas over increasingly greater distances. Internet online stores, such as Sizo-mag, invite prisoners and their families to use their shopping facilities in order to avoid the hassle of sending parcels, which may not pass security controls. But overwhelming empirical evidence of human rights abuses in Russian prisons suggests that these new phenomena are also new variants of Potemkin villages for the virtual age. Stores delivering goods to pretrial detention centers show images of abundance on their websites, as in Figures 8a and 8b.

8a

8b

The online store that bills itself as VIP advertises lemons, oranges, and pomegranates as “new items.” The background image for the website’s logo shows scales of justice, followed by a misspeled Latin quote that reads “Recte fructus recisse mercess [sic] est,” which means roughly “The fruit of having done the right thing is the deed itself.”

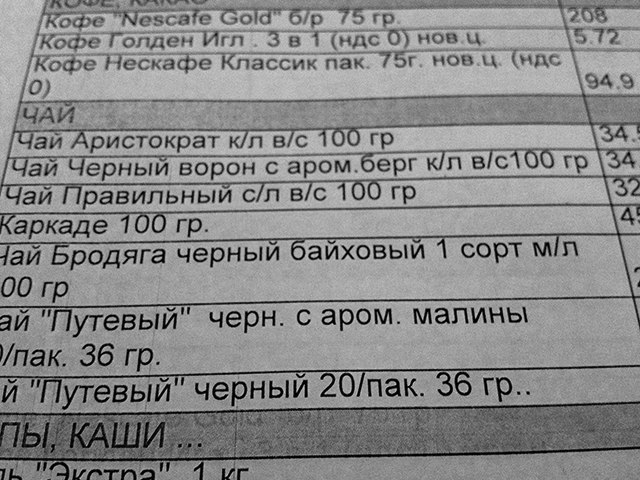

In practice, not only are these Internet shops very expensive and the prisoners’ own shopping transactions limited according to their crime, the selections of goods available inside detention centers and prison colonies also feature an entirely different lexicon of product names. While, as in Figure 9, we can also see that foreign brands such as Nescafe and Golden Eagle remain on offer, they are followed by a tea selection that uses jargon from the world of incarceration. For instance, one tea is called “Black raven” (chernyi voron), an allusion to the popular nickname for the car that picks up convicts from their homes to drive them to prisons. There are also “Vagabond” (brodiaga) tea and “Drifter” (neputevyi) tea, in the sense of good-for-nothing.

Moreover, periodically, regulations about permissible goods are changed on the whim of institutional administrators. For example, in October 2013, the FSIN-run online store (www.sizomag.ru) announced that cucumbers and tomatoes were “prohibited” from online sales at Samara pretrial detention centers.[19]

It is mostly inmates’ relatives who send food parcels through online services, which are subject to weight limitations and sometimes frequency. As prisoners’ rights activists attest, the introduction of online food supplies is nonetheless welcome because it increases the chances of a food parcel reaching the incarcerated; by contrast, in the case of parcels delivered in person, a large number of products were destroyed or not allowed to pass the prison regulations. At the same time, the Internet and its financial forms provide an even more radical form of exclusion for the imprisoned population. As the businessman Aleksei Kozlov, imprisoned from 2009 to 2013, wrote in his blog, which was then maintained by his wife, the journalist and human rights activist Ol’ga Romanova, spending two years without Internet made him alert to what extent his social life and his life as a political subject had relied on the Internet before his imprisonment (Kozlov 2010). To compensate for this isolation, friends and family gave him drawings of his wife’s Facebook page, which contained references to recent news and publications. Romanova told me in an interview that while in prison Kozlov was able to telephone a local supermarket using a printout from the supermarket’s online catalogue.[20] Other surrogates for Internet services included digests of news and information about new developments in technology, which friends provided him with. But what allowed him to order food by phone was the fact that he could provide his bank details at home. This was by far an exception. Even when Internet shopping was introduced to his prison colony, only a few of his fellow inmates, most of whom had not used the Internet for this purpose before, went on to use this service. Most of them continued buying goods in the old-style prison store on wheels on the grounds, as in Figure 10.

At the practical level, the Moscow Helsinki Group’s Nina Tagankina, who has been visiting prison colonies across Russia since the mid-1990s, remarks that the availability of computers and the Internet, like the availability of televisions, often depends on private initiatives by inmates’ relatives and the prison administration.[21] Moreover, in some cases, even the prison administration itself has no recourse to computers. In one case, Tagankina and her colleague were asked to help set up a computer with Internet facilities for the prison administration, and only then was another such computer set up for use by prisoners.

Making Prison Identities Online

The websites maintained by FSIN, as well as the media coverage of penitentiaries, have also become a site for shaping social identities. The first of these is the collective identity of the inmates, or zeki. On November 27, 2009, the Russian tabloid Moskovskii komsomolets, for instance, reported, with its peculiar sense of humor, that the zeki, the slang word for prison inmates derived from the abbreviated “zakliuchennye,” could now “catch” their food through the Internet (Merkacheva 2009). Internally, by labeling goods and services with prison jargon (like “Black raven” and “Vagabond” teas), the administration creates a particular category of persons that is linguistically separated from the rest of the population even when it consumes the same goods. To the outside world, meanwhile, they produce what the websites of FSIN call “souvenirs,” although it remains unclear what exactly these souvenirs commemorate. There are some motifs from Russian history, but the souvenirs on offer are not restricted to those. One particularly prominent theme is warfare, and another one is hunting. For example, souvenirs made in correctional institutions of Omsk Oblast’ include replicas of daggers and sabers from the Napoleonic wars called “Revenge” or “Liberator,” woodwork including reliefs of hunting a wild elk, and a globe resting on three elephants which is more reminiscent of Chinese myths of creation than of Russian ones.[22]

A second aspect is the construction of gender roles and stereotypes. This is visible in the way products are categorized in the online services into “male” and “female” goods. For example, VIP-SIZOSERVICE (Figure 11) advertises differentiated food parcels for men and women.

Prices for male packages are slightly higher than for female packages, between 4,520 rubles for women and 4,700 for men (the equivalent of $141). Indeed, one of the reasons why the Internet stores have been praised is that many items related to feminine hygiene, which are available in online shops for prisoners, cannot be sent to colonies by other means because they are not on the list of permitted items (Petelin and Maetnaia 2012).

A third level at which the online stores configure identity is by both affirming and transcending the isolation of prisoners in terms of geography and markets. Here, the exposure of prisoners to online goods merely highlights a general aspect of the post-Soviet Russian economy, which continues to rely on foreign imports for a variety of consumer products, but also appeals to nostalgia for Soviet times. Images of parcels advertised on online store sites show imported hygiene items, produce, and and groceries, such as Granny Smith apples and garlic from China, Heinz Tomato ketchup and Lipton tea. But even in cases where goods are made in Russia, they refer consumers to the idea of “foreign countries” at the level of images. For example, one online shop offers notebooks “Cities of Europe,” which are manufactured by a Moscow-based company but display images of European landmarks like London’s Big Ben. But there is also another notebook for sale from the same retailer—featuring the austere Soviet look and named after the Russian city of Bryansk.[24]

A further example of the way the Federal Penal Service creates social identities through online services is the return of ethnic and religious stereotyping in prisons, in addition to gender stereotyping. On the official FSIN website, there are two links to forums for prisoners which are not run by the government but are recommended as public resources.[25] One has a neutral title of “Forum about prison life” (www.forumtyurem.net), while another link is to the website called “Shalom to you, prisoner!” (www.shalom-zk.ru) that is directed specifically at prisoners of Jewish origin. FSIN itself gives no statistics on the ethnic or religious origin of its inmates, even though it guarantees freedom of religious service in prisons. Considering, as “Shalom to you, prisoner!” states, that Jews form only about 0.05 percent of criminals in Russia, the question is why one out of two links to forums on FSIN’s website directs readers specifically to this resource, rather than to the dozens of more general social networks assisting prisoners and their families. Jews and Muslims are highlighted once more as consumers of goods in prisons in the new online shopping facilities. The FSIN-run Internet store for Moscow correctional facilities, for instance, offers kosher and halal food.[26] This emphasis on ethnic and gender stereotyping seems to be an integral part of the new ordering regime in Russian prisons that still, however, awaits ideological justification or explanation; rather, it proceeds in an ideological vacuum.

The Internet as a Site of Resistance

At the same time as being a tool of control and group identity management, the Internet has also come to play an important role as a resource for civic engagement and the critique of power. In the Soviet period, the main resource through which political dissidents sought to transcend government repressions was the Chronicle of Current Events (Khronika tekushchikh sobytii). It was a samizdat publication in which dissidents shared their news, as well as legal and practical advice.[27] As a means of challenging the regime, whose repressive power relied on limiting communications with prisoners to a minimum, it was a tool of mutual solidarity with a transnational impact, as some recent studies have shown (e.g., Kind-Kovács and Labov 2013).

In today’s Russia, some of the web-based social networks associated with LiveJournal and other communities, arguably, follow and develop this model (Gusejnov 2000, forthcoming). Through services like FSIN-pis’mo, intermediaries can help prisoners in different colonies and prisons correspond with each other, with the media, and the outside world. Prominent examples are blogs and letters by the imprisoned businessmen Mikhail Khodorkovskii, which have regularly been made public on social networks and public media since 2005 (even though he has been imprisoned since 2003), and the aforementioned Aleksei Kozlov. Also in the past decade, a host of dedicated websites emerged that serve the purpose of consolidating information, exchanging experiences, and crowdfunding among prisoners and their families, the most prominent of which is Rus’ sidiashchaia, which grew out of Ol’ga Romanova’s solidarity network in support of her husband. Numerous other websites and virtual social networks such as No to Gulag (www.gulagu.net) and RosUznik (rosuznik.org) have also been established to offer legal and practical advice to families of the incarcerated and to help them organize. These websites discuss everything from techniques on how to prepare parcels that will be less likely to be tampered with by the prison administration before reaching the addressees to psychological advice on how to deal with separation. They give basic information concerning the location and character of different types of penal colonies and actively call on witnesses to come forward in support of the accused. Likewise, in 2012 the Sakharov Center, a human rights organization in Moscow, has started a series of seminars on prison economies, which are themselves broadcast via its own Internet-based TV channel to a Russian and global audience of viewers. This use of the Internet is reminiscent of what David Scott and Helen Codd have called “critical and anti-prison activism” (2010:168).

Conclusions

When it comes to discussing the unevenness of modernization, the questions that motivated me to approach Judith Pallot and Yvonne Jewkes ultimately come back to this: is the Russian experience of “uneven modernity,” where the sphere of the digital enters the sphere of punishment, exceptional? Or are all prisons, including Russian ones, becoming, in Nils Christie’s words, “Gulags, Western style” (Christie 1993)—that is, more humane-looking sites of dehumanization?

Nearly two decades ago, theorists of modernity suggested that thanks to new technologies of production and communication, modern societies could annihilate the significance of spatial and cultural distance for human life, leaving only time as a relevant category of human experience (Cairncross 1997). In the period of modernity, they argued, with the help of technologies such as telephones and the Internet, distance as an objective measurement would lose relevance; proximity and distance between human beings and groups would no longer correspond to their being located in proximity to each other. Instead, human distance would measure proximity by the intensity of interactions through virtual means. But the intensity and speed with which modern technologies like the Internet annihilate some forms of distance have proved to be so uneven that the opposite effect may have occurred. This is not only the case in Russia but also in the United States, which has large disparities in terms of the permeation of Internet technologies in peripheral regions of the country (US Census Bureau 2013:9). In terms of numbers by region, predictably, the two maps are complementary opposites: just as in Russia, in the United States, the intensity of Internet usage per 100,000 residents is highest in those regions (the urban metropolitan centers) where the intensity of incarceration is lowest.[28] The incarcerated who are based in those penal peripheries are twice removed from reality: by physical and by virtual distance; but so is the free population residing in these areas. The question is how this dissociation of physical from real human distance in the course of modernization impacts the practice of punitive isolation.

An initial comparison between critiques of British and American prisons might suggest even greater parallels between Russia and the United States at the level of the corporate governance of prisons and the deprivation of prisoners of their rights as citizens (Dilts and Harcourt 2008). The websites that are maintained by FSIN are not unlike the merchandise services provided by multinational corporations specializing in prison provisions as so-called punishment services, such as the French multinational Sodexo, the American Aramark, or the British security firm G4S. British company JPay describes itself as a private company that partners with state, county, and federal correctional facilities to provide safe, reliable, and convenient services for family and friends of inmates and payment solutions for offenders, parolees, and probationers. The originally French multinational Sodexo also provides food services for British and US prisoners. In France, comparable services were launched earlier in the 2000s and are available to regular prisoners, not just to those in pretrial detention. Sodexo originally specialized in hotel foods but then branched out to schools, conferences, and correctional facilities. All these facilities speak the language of services in a way that is not dissimilar from the Russian case, where websites promise to save relatives “time, money, and nerves.”

Earlier theorists of modernization suggested that new technologies contribute in this way to the making of uniform and increasingly interchangeable social identities (e.g., Jameson 1984; Cairncross 1997). However, it seems that processes of uneven modernization might correct this impression (as described by David Harvey [2006] and others). The digital forms of ordering human statuses seem, on the contrary, to have contributed to greater fragmentation of concepts of the human even within the boundaries of one state. Communities of exclusion, which for a variety of reasons cannot form part of the larger process of modernization that characterizes the society of which they are a part, are a characteristic feature of partial modernization. The inhabitants of prisons, detention centers, and penal colonies are merely the most extreme examples of such a community within a community, isolated from a number of goods available to the rest of society, one of which is new technology. Another such population group that could be differentiated by its specific social situation of deprivation is the community of free citizens who have no access to the Internet despite the fact that nobody excluded them from these goods by law.

In this introductory essay, I wanted to draw attention to the Internet not only as an instrument of revelation but also as a new form of concealment, not just as a space of representation of violence but also as an instrument of violence, not only as a space for critique of state violence by social activists but also as a site of complicity. While critics of Soviet authoritarianism such as Mikhail Bakhtin (1981) have associated totalitarian control with monologue and freedom with the “dialogic imagination,” the multiple function of the Internet complicates this optimistic view of dialogue. Some dialogues cannot easily transcend the hierarchies imposed on them from outside, as the case of e-mailed and scanned letters from convicts might suggest. These ambivalent and highly complex communication practices call for future empirical and theoretical research. The following contributions from Judith Pallot and Yvonne Jewkes will serve as expert guidance to this subject.

In penitentiaries, introducing the digital may bring no revolutionary changes to the logic of its violence at all, despite the prevalence of the concept of a “digital revolution” elsewhere. But at the level of forming communities of resistance, a certain change is discernible, in the sense that the Internet communities provide a less exclusive and wider version of the Soviet-era dissident Chronicle of Current Events. At the same time, we must note that there is a third, gray zone of change which seems to be neither enforcing nor resisting the dehumanizing forms of Russian penal practice: this is the sphere of normalization. It is here that the Internet reveals its dimension as a new and more powerful Potemkin village than Catherine the Great and her Prince could ever build.

References

- Allina-Pisano, Jessica. 2008. The Post-Soviet Potemkin Village: Politics and Property Rights in the Black Earth. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Bakhtin, Mikhail. 1981. The Dialogic Imagination: Four Essays. Translated by Caryl Emerson and Michael Holquist. Austin: University of Texas Press.

- Barbançon, Louis-José. 2003. L’archipel des forçats: Histoire du bagne de Nouvelle-Calédonie, 1863–1931. Paris: Presses Universitaires de Septentrion.

- Bellamy, Christine and John A. Taylor. 1998. Governing in the Information Age. Buckingham, UK: Open University Press.

- Brus, Włodzimierz, Pierre Kende, and Zdeněk Mlynář. 1982. “Normalization” Processes in Soviet-Dominated Central Europe: Hungary, Czechoslovakia, Poland. Cologne: Index.

- Cairncross, Frances. 1997. The Death of Distance: How the Communications Revolution Will Change Our Lives. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

- Castells, Manuel. 2009. Communication Power. Oxford: Oxford University Press

- Chadwick, Andrew. 2006. Internet Politics: States, Citizens, and New Communications Technologies. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Christie, Nils. 1993. Crime Control as Industry: Towards Gulags, Western Style. London: Routledge.

- Corston Report. 2007. A Report by Baroness Jean Corston of a Review of Women with Particular Vulnerabilities in the Criminal Justice System. UK Home Office. Retrieved October 30, 2013 (http://www.justice.gov.uk/publications/docs/corston-report-march-2007.pdf).

- Dilts, Andrew and Bernard Harcourt. 2008. “Discipline, Security, and Beyond: A Brief Introduction.” Carceral Notebooks 4:1–6.

- Dizard, Wilson P. 1997. Meganet: How the Global Communications Network Will Connect Everyone on Earth. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

- Doklad o deiatel’nosti Upolnomochennogo po pravam cheloveka v Leningradskoi oblasti v 2011 godu. Razdel 9. Retrieved October 30, 2013 (http://www.ombudsman47.ru/deystviya-bezdeystviya-sotrudnikov-pravoohranitelnyh-organov-voprosy-soblyudeniya-prav-lits-soderzhashihsya-pod-strazhey-i-nahodyashihsya-v-mestah-lisheniya-svobody-kontrol-za-oborotom-narkotikov-.html).

- Durkheim, Émile. 1899–1900. “Deux lois de l’évolution pénale.” Année sociologique 4:65–95.

- Etkind, Alexander. 2011. Internal Colonization: Russia’s Imperial Experience. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- European Court of Human Rights. 2013. Analysis of Statistics 2012. Retrieved on October 20, 2013 (http://echr.coe.int/Documents/Stats_analysis_2012_ENG.pdf).

- Fanon, Frantz. 1967. Black Skin, White Masks. New York: Grove Press.

- Foucault, Michel. 1975. Surveiller et punir. Paris: Gallimard.

- Fulbrook, Mary, ed. 2009. Power and Society in the GDR, 1961–1979: The “Normalisation of Rule”? New York: Berghahn Books.

- Garland, David. 2001. The Culture of Control: Crime and Social Order in Contemporary Society. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Goncharov, Artur and Pavel Lebedev. 2011. “Potentsial razvitiia interneta v regionakh.” FOM Media, July 11. Retrieved April 13, 2013 (http://fom.ru/blogs/10119).

- Gong, Haomin. 2012. Uneven Modernity: Literature, Film, and Intellectual Discourse in Postsocialist China. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press.

- Gusejnov, Gasan. 2000. “Zametki k antropologii russkogo interneta.” Novoe literaturnoe obozrenie 43. Retrieved August 25, 2013 (http://magazines.russ.ru/nlo/2000/43/main8.html).

- Gusejnov, Gasan. Forthcoming. “Divided by a Common Web: Some Characteristics of the Russian Blogosphere.” In Digital Russia: The Language, Culture and Politics of New Media Communication, edited by Michael Gorham, Ingunn Lunde, and Martin Paulsen. London: Routledge.

- Harvey, David. 2006. Spaces of Global Capitalism: Towards a Theory of Uneven Geographical Development. London: Verso.

- Horst, Heather A. and David Miller, eds. 2012. Digital Anthropology. Oxford: Berg.

- Interfaks. 2012. “‘Levada-tsentr’: internetom pol’zuetsia uzhe bolee poloviny naseleniia Rossii.” Vedomosti, November 11. Retrieved April 13, 2013 (http://www.vedomosti.ru/politics/news/5942671/levadacentr_internetom_polzuetsya_uzhe_bolee_poloviny).

- Jameson, Fredric. 1984. “Postmodernism, or, The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism.” New Left Review 146:53–92.

- Jewkes, Yvonne, ed. 2003. Dot.cons: Crime, Deviance and Identity on the Internet. Cullompton, UK: Willan.

- Jewkes, Yvonne. 2007a. “Prisons and the Media: The Shaping of Public Opinion and Penal Policy in a Mediated Society.” Pp. 447–467 in Handbook on Prisons, edited by Yvonne Jewkes. Cullompton, UK: Willan.

- Jewkes, Yvonne, ed. 2007b. Crime Online. Cullompton, UK: Willan.

- Jewkes, Yvonne. 2011. Media and Crime. Revised 2nd ed. London: Sage.

- Kim, Joohan. 2001. “Phenomenology of Digital-Being.” Human Studies 24(1/2):87–111.

- Kind-Kovács, Friederike and Jessie Labov. 2013. Samizdat, Tamizdat, and Beyond: Transnational Media during and after Socialism. New York: Berghahn Books.

- Kortunova, Ol’ga. 2013. “Liubitel’ rabskogo truda zakliuchennykh, ‘predprinimatel’’ Vladimir Golovnev.” Kniga ucheta myslei (blog), September 26. Retrieved October 18, 2013 (http://efa2007.livejournal.com/641160.html).

- Kozlov, Aleksei. 2010. “Prigovor: dva goda bez interneta.” Forbes, Butyrka-blog, June 2. Retrieved October 18, 2013 (http://www.forbes.ru/blogpost/50713-prigovor-dva-goda-bez-interneta).

- Lefebvre, Henri. 1991. The Production of Space. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Lenta.ru. 2013. “Pravozashchitniki obnaruzhili v kolonii Tolokonnikovoi sistemu prinuditel’nogo truda.” October 1. Retrieved October 17, 2013 (http://lenta.ru/news/2013/10/01/labour1).

- Maetnaia, Elizaveta and German Petelin. 2013a. “Tiuremnuiu sviaz’ otdadut kommersantam.” Izvestiia, August 23. Retrieved October 19, 2013 (http://izvestia.ru/news/555913).

- Maetnaia, Elizaveta and German Petelin. 2013b. “Koloniia N. 14 obshivaet byvshego deputata Gosdumy.” Izvestiia, September 26. Retrieved October 5, 2013 (http://izvestia.ru/news/557694).

- Mann, Michael. 1993. “Nation-States in Europe and Other Continents: Diversifying, Developing, Not Dying.” Daedalus 122(3):115–140.

- Margolin, Yulii. 1949. Puteshestvie v stranu ze-ka. Paris: YMCA Press.

- Meier, Andreas. 2012. eDemocracy and eGovernment: Stages of a Democratic Knowledge Society. Berlin: Springer.

- Merkacheva, Eva. 2009. “Zeki loviat edu setiami: Ugolovnikam razreshili prinimat’ peredachi cherez internet.” Retrieved October 31, 2012 (http://www.mk.ru/social/article/2009/11/26/392623-zeki-lovyat-edu-setyami.html).

- Pallot, Judith. 2005. “Russia’s Penal Peripheries: Space, Place and Penalty in Soviet and Post-Soviet Russia.” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 30(1):98–112.

- Pallot, Judith and Laura Piacentini. 2012. Gender, Geography, and Punishment: The Experience of Women in Carceral Russia. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Pashukanis, Evgenii. 1932. Proletarskoe gosudarstvo i postroenie besklassovogo obshchestva. Moscow: Partiinoe izdatel’stvo.

- Petelin, German and Vladimir Barinov. 2013. “Eks-glavu FSIN podvodiat pod delo o brasletakh.” Izvestiia, April 2. Retrieved October 17, 2013 (http://izvestia.ru/news/547896).

- Petelin, German and Elizaveta Maetnaia. 2012. “FSIN urezala arestantam shoping.” Izvestiia, December 20. Retrieved October 18, 2013 (http://izvestia.ru/news/541925#ixzz2I4kNcZl5).

- Redaktsiia FOM. 2013. “Internet v Rossii: Dinamika proniknoveniia. Zima 2012–2013.” FOM Internet, March 13. Retrieved September 1, 2013 (http://runet.fom.ru/Proniknovenie-interneta/10853).

- Rozhkova, Natal’ia. 2013. “Sledy Tolokonnikovoi vedut na Maiami i Kipr.” Moskovskii komsomolets, October 3. Retrieved October 19, 2013 (http://www.mk.ru/social/article/2013/10/02/924715-sledyi-tolokonnikovoy-vedut-na-mayami-i-kipr.html).

- Rusche, George and Otto Kirchheimer. 1939. Punishment and Social Structure. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Schutz, Alfred. 1932. Der sinnhafte Aufbau der sozialen Welt: Eine Einleitung in die verstehenden Soziologie. Vienna: Springer.

- Scott, David and Helen Codd. 2010. Controversial Issues in Prisons. Maidenhead, UK: McGraw-Hill International.

- Smith, Neil. 1984. Uneven Development: Nature, Capital and the Production of Space. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Solzhenitsyn, Aleksandr. 1973–1975. Arkhipelag GULAG. 3 vols. Paris: YMCA Press.

- Stampp, Kenneth. 1956. The Peculiar Institution: Slavery in the Ante-Bellum South. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

- Tabakh, Anton. 2012. “‘Tainstvennyi ostrov’: Sovremennaia rossiiskaia penitentsiarnaia sistema kak ekonomicheskii sub”ekt i fenomen.” Paper presented at the seminar “Penal Economies” at the Sakharov Center, November 1, Moscow. Retrieved April 13, 2013 (http://gogol.tv/video/579#playAll).

- Telekanal Dozhd’. 2013. “Glava finansovo-ekonomicheskogo upravleniia FSIN o Tolokonnikovoi, kvartirakh v Maiami i nekhvatke marketologov v tiur’me.” October 2. Retrieved October 29, 2013 (http://tvrain.ru/articles/glava_finansovo_ekonomicheskogo_upravlenija_fsin_o_tolokonnikovoj_kvartirah_v_majami_i_nehvatke_marketologov_v_tjurme-353544).

- Tolokonnikova, Nadezhda. 2013. “Vy vsegda teper’ budete nakazany.” Lenta.ru, September 23. Retrieved October 12, 2013 (http:///www.lenta.ru/articles/2013/09/23/tolokonnikova).

- Toth, Stephen A. 2006. Beyond Papillon: The French Overseas Penal Colonies, 1854–1952. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

- Ugolovno-ispolnitel’nyi kodeks Rossiiskoi Federatsii ot 8 ianvaria 1997 goda N 1-FZ. Retrieved October 15, 2013 (http://www.consultant.ru/popular/uikrf).

- United Nations. 2012. E-Government Survey 2012: E-Government for the People. Retrieved October 30, 2013 (http://unpan1.un.org/intradoc/groups/public/documents/un/unpan048065.pdf).

- US Census Bureau. 2013. “Computer and Internet Use in the United States: Population Characteristics.” US Department of Commerce Economics and Statistics Administration. Retrieved August 25, 2013 (http://www.census.gov/hhes/computer).

- Veselov, Andrei. 2013. “Ekonomika tiur’my: Kak zarabatyvaet rossiiskaia zona.” Russkii reporter, October 1. Retrieved October 18, 2013 (http://rusrep.ru/article/2013/09/30/prison).

- Vial, Stéphane. 2013. L’être et l’écran: Comment le numérique change la perception. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France.

- Voronina, Iulia. 2013. “Koshelek ili set’.” Rossiiskaia gazeta, August 28. Retrieved October 18, 2013 (http://www.rg.ru/2012/08/28/platezhi.html).

- Williams, Eric. 1944. Capitalism and Slavery. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

- Williams, Kieran. 1997. The Prague Spring and Its Aftermath: Czechoslovak Politics, 1968–1970. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Шопинг в сизомаге: интернет как потемкинская деревня пенитенциарных практик современной России

Дина Гусейнова – стипендиат Фонда Леверхульма и научный сотрудник Центра транснациональной истории (Университетский колледж Лондона). Адрес для переписки: Gower Street, London, WC1E 6BT, UK. d.gusejnova@ucl.ac.uk.

Некоторые теоретические предпосылки этого эссе основаны на исследовании роли лагерей военнопленных в культурной истории ХХ века, которое осуществляется при поддержке Фонда Леверхульма. Я хочу выразить благодарность Ольге Романовой и Петру Курьянову («Руcь сидящая»), Анастасии Овсянниковой (Сахаровский центр) и Нине Таганкиной (Московская Хельсинкская группа) за готовность поделиться со мной идеями и опытом работы по исследованию и критике пенитенциарных учреждений в постсоветской России; при этом ответственность за любые ошибки в данном эссе остается за мной. Кроме того, я благодарна Ольге Романовой за разрешение использовать фотографии из ее архива.

Целью данного введения и нижеследующей дискуссии является изучение роли интернета в пенитенциарной практике и социальной экономике наказания в постсоциалистической России. В современном обществе интернет выполняет целый ряд функций; это и информационный ресурс, и средство общения, и инструмент управления. Мое вступительное эссе основано на методике, которую можно было бы назвать дигитальной феноменологией российского интернета. Дополнением ему служат интервью с экспертами и подборка фотографий из личного архива Ольги Романовой. При этом эссе предлагает всего лишь обзор исследовательских вопросов и дает только предварительные ответы, которые позволяют определить социальную значимость предоставляемых c 2009 года интернет-услуг в пенитенциарных учреждениях России и рост интернета как средства информации о тюрьмах и заключенных. Вопреки терминологии модернизации, которую правительства и корпорации обычно используют при внедрении новых цифровых технологий, их практическая реализация в исправительных учреждениях предполагает в лучшем случае неравномерный «уровень современности». Рассматривая российский опыт в этой области, данное эссе и сопровождающие его интервью с Джудит Пэллот и Ивонн Джукс призывают использовать теории «неравномерной современности» и «нормализации» для разработки критического подхода к изучению российского примера как в сравнительной, так и в диахронической перспективе.

Ключевые слова: пенитенциарные учреждения; электронное управление; постсоветские исследования; неравномерная современность; теории модернизации; национальное государство; технологии коммуникации; история интернета

- http://ik12.kem.uiszakaz.ru. ↩